“Winterreise” at Ustinov Studio, Bath

Simon Thomas in the South West

14 June 2024

During her all-too-brief tenure as Artistic Director of the Ustinov Studio, Bath, Deborah Warner has programmed classic plays (including The Tempest, which she directed herself) alongside dance and song events. Opening her third and final season is a staging of Schubert’s great lieder cycle Winterreise (Winter Journey) featuring the celebrated English tenor Ian Bostridge, who is something of a specialist in the piece.

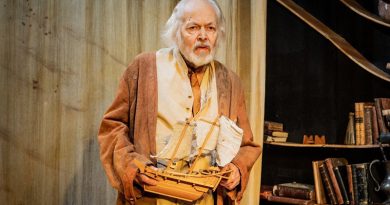

Ian Bostridge.

Photo credit: Claire Egan.

Bostridge has lived with the work for many years, performing it, making a film about it, staging an orchestrated version, and even writing a book. In his programme notes, culled from his book Schubert’s Winter Journey: Anatomy of an Obsession, he declares it one of the greatest works of Western culture and explores the world of the cycle, citing Shakespeare, Dante, Proust, and Samuel Beckett, through to Bob Dylan, Frank Sinatra, and Billie Holliday.

There’s a quote from Beckett’s final play What Where (“It is winter. Without journey. Time passes. That is all. Make sense who may. I switch off.”); Beckett was also a great admirer of Schubert, even naming one of his later plays Nacht und Träume (Night and Dreams) after the Austrian composer’s song of the same name.

There is something of Beckett’s aesthetic in the staging Deborah Warner has conjured up from the bare bones of the work, in conjunction with assistant director Isabelle Kettle and designer Justin Nardella. It’s all monochrome starkness with nods towards the nuanced textures of Schubert and poet Wilhelm Müller’s creation in the sheet of ice, shallow box of snow, smear of gravel, and fragment of flagstone that pave the wanderer’s tragic journey through a bleak frozen landscape. A white screen, set obliquely to the audience’s vision, presents further opportunities for casting wintry patterns through projections that also hazily haunt the black background of the other walls.

Any performance of Winterreise is a dramatic event, so intense and harrowing is the through-narrative of Müller’s poems and Schubert’s chilling piano accompaniment. It’s tempting to think that any attempt to go beyond the vivid word-painting and tortuous atmosphere is unnecessary for a song cycle that even in concert can be overwhelming. Warner has form in this kind of thing, having staged Bach’s passions and Handel’s Messiah in a similar way, albeit on a much larger scale. The degree of success of such ventures will vary for each person attending.

Bostridge is renowned more as a concert artist than a stage performer, although there have been effective opera roles such as his tortured and fragile Aschenbach in Britten’s Death in Venice at English National Opera, also directed by Warner. At times, Bostridge’s histrionic performance here, thrashing around in paper snow and flinging himself at walls, seems more than is needed to communicate the decline of the character’s mental faculties as he journeys further from the longed-for romantic comfort of an unknown girl into a land of gravestones and the mysterious roadside hurdy-gurdy man (symbolizing what exactly?) who ends the piece.

Schubert wrote the work towards the end of his short life in 1828 and there’s something of Goethe’s Young Werther in the outsider lost in an internal landscape that is bleaker and more bitter than the external one he journeys through. There’s heartbreak in every bar of Schubert’s score, even in those fleeting moments of hope such as the post-horn arrival of the mail with no word from the loved one and the brief dream of May flowers, kisses, and cuddles.

Bostridge is joined by his long-time collaborator, pianist Julius Drake, perhaps the most sensitive and accomplished accompanist working today. Warner’s decision to include a third, uncredited, performer is questionable. Lurking moodily throughout, seated in the lap of the audience, his purpose only becomes apparent at the very end and then it’s debatable as to whether it adds anything.

There is something of a coup de théâtre, though, in the flooding of the stage with natural light during the penultimate song in which the wanderer sees three suns. It is a burst of what may be optimism among all the gloom, real life suddenly banishing the artificiality of the room along with the wretched man’s view of himself. It’s an alarming and exhilarating moment.

With recitals to come by mezzo Catherine Wyn-Rogers and counter tenor Iestyn Davies, nestling intriguingly alongside a Richard Jones production of Pinter’s The Birthday Party, Deborah Warner’s last shout in Bath looks as though it will be a loud and significant one.