“Bitter Wheat”: Garrick Theatre

Neil Dowden in the West End

1 September 2019

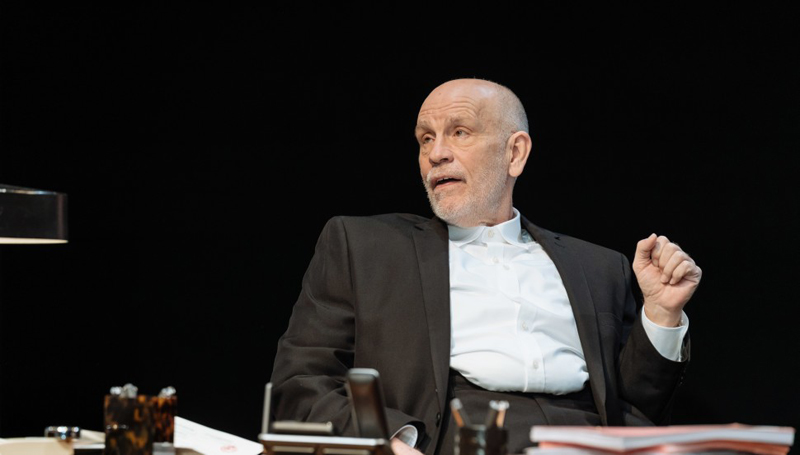

There was much hype ahead of the world premiere of David Mamet’s Bitter Wheat at the Garrick Theatre. A new work by one of the world’s most lauded if controversial playwrights “inspired by” (if that is the correct phrase) the disgraced movie mogul Harvey Weinstein would in itself have received a lot of attention. But added to this was the fact that international screen and stage star John Malkovich was playing the leading role, in his first performance in the West End for almost 30 years — and, remarkably, his first collaboration with Mamet, who also directs.

John Malkovich and Matthew Pidgeon. Credit: Marc Brenner.

Unfortunately, though, Bitter Wheat is a bitter disappointment. Rather like Martin McDonagh’s damp squib A Very Very Very Dark Matter at the Bridge Theatre last year, it’s not that there aren’t interesting elements in the show. It’s more that the end product falls so short of expectations. And, similarly, the major responsibility lies not with the starring performance (Malkovich is moderately entertaining within the limitations of his character, as was Jim Broadbent in his portrayal of Hans Christian Andersen) but with the deeply flawed writing.

Mamet’s satirical black comedy focuses on the larger-than-life figure of Barney Fein, an Oscar-winning Hollywood producer who ruthlessly abuses his power both as a bully and as a sexual predator. We first see him in action in his plush office launching into a screenwriter whom he has refused to pay. We also watch him order a doctor to give him a sexually stimulating drug. And we witness his high-handed treatment of his long-suffering personal assistant and new intern. But Fein’s grossly intimidating behaviour goes much further when he tries (and fails) to forcibly seduce a young British-Asian actress. His resulting downfall induces not shame but a desperate attempt to cling on to his status, even attempting to use his mother’s recent bizarre murder in his favour — remorselessly manipulative to the bitter end.

There’s no doubt that Fein is modelled on Weinstein — even their names are similar. There are individual details (such as references to commercial arthouse films with a “humanitarian” message and having a work meeting with the actress in a hotel room when he wears a dressing gown and requests a “massage” while showering) that make him not just a generic abuser. But Mamet’s prime target seems to be the corruption of the Hollywood studio system itself (with the film industry as a cut-throat corporate capitalist world masquerading under art and entertainment), based on his own disillusioning experiences of it. He is less concerned with the kind of sexual abuse which led to the creation of the #lMeToo movement. The main problem with this is that, once again, women’s voices are marginalized in favour of an alpha male who may be a monster but who has by far the lion’s share of the dialogue.

Of course, Mamet is well known for his depiction of toxic masculinity in plays like American Buffalo, Glengarry Glen Ross, and Speed-the-Plow (also a satire on Hollywood), not to mention many of his films. And he has even been accused of misogyny himself, because his female characters rarely get a fair crack of the whip. The political correctness-challenging Oleanna notoriously divided audiences along gender lines due to its confrontational set-up in which a female student falsely accuses her male professor of sexual harassment. Bitter Wheat is not a counterweight, however: there is no doubt that Fein is a nasty piece of work, yet there is little sense of the deep damage he has inflicted on women in particular.

Alexander Arnold, John Malkovich, Ionna Kimbook, Doon Mackichan.

Credit: Marc Brenner.

But even on its own terms of cynical humour, Bitter Wheat falls flat. Mamet is famous for writing terrific barbed banter, but here he strains too hard to be funny. Fein has some witty lines (e.g. the self-justifying: “l don’t think you understand how much money I gave to the Democratic Party”), but his relentlessly sardonic quips bear diminishing returns. There are also less than amusing jokes about filming a Korean Gone with the Wind or a gay drama about Anne Frank. lt has to be said that although Mamet’s direction is slick, he is self-indulgent with his own text.

On stage throughout, the fat-suit-wearing Malkovich is grotesquely dominating as Fein. His funniest moment is when he falls on his back and like a beetle is unable to get up again, but his one-note delivery becomes rather monotonous. He suggests a mixture of cynicism, vulgarity, paranoia, and self-loathing — he is repulsive but fatally lacks a sense of real menace (which Malkovich has conveyed so powerfully in other roles). His pathetic excuse: “The overweight get no sympathy” seems like superficial psychology from a character rounded only in physique.

Despite an underwritten part, Doon Mackichan does well as Fein’s pragmatic personal assistant who facilitates his abuse, and Yung Kim Li also impresses as the self-possessed actress who stands her ground.

Mamet’s most recent plays which opened in New York were not well received and have not made their way to London. The last one here was the underwhelming Race at Hampstead Theatre in 2009. There have been some first-rate revivals of his earlier, great work, but Bitter Wheat suggests that he may well be a spent force as a playwright.