“The Unbelievers” at Royal Court Theatre Downstairs

Neil Dowden in West London

★★★★☆

27 October 2025

Nick Payne – best-known for his award-winning, multiverse romantic drama Constellations –returns to the theatre from screenwriting with his first full-length play since Elegy at the Donmar Warehouse in 2016. The Unbelievers is an uneven but moving and surprisingly funny examination of the different ways members of a family react to the disappearance of their 15-year-old son/brother Oscar – and how it threatens to split them apart. In a tightly focused production by Marianne Elliott, the fine cast is led by Nicola Walker giving an outstanding performance as the mother Miriam who will not give up hope whatever the cost to other relationships.

Photo credit: Brinkhoff/Moegenburg.

Written in an intriguing, elliptical style, The Unbelievers is split between three separate timelines: the week following Oscar’s disappearance, one year on, and seven years later, with the scenes bleeding into each other sometimes confusingly. It’s not immediately clear why Payne has done this, but it may suggest the way time fractures under extreme psychological distress. What does become apparent though is how the family come together in the short term for mutual support but over the years diverge as the others try to move on with their lives while Miriam is frozen in obsessive feelings of grief and guilt. In a play that looks at different aspects of faith, for Miriam they are “the unbelievers”.

It begins in media res with Miriam’s hand wrapped in a bloody scarf. She has just returned home from Beverley in Yorkshire following up yet another false sighting of Oscar, but had to break into her car (using a gnome!) as she mislaid the keys – a sign that she is starting to crack up under the strain, as we learn it is one year since the disappearance. Then the action moves back to just after the event, as the family tell the police about the last dinner with Oscar when everything seemed normal. Then it moves forward with Miriam’s former husband (and Oscar’s father) David planning a memorial after seven years which Miriam objects to as being like a “funeral”. And so on as we piece together the overall picture of an increasingly broken family.

There are no clues as to what has happened to Oscar – whether he voluntarily decided to run away, if he is still alive – as Payne is more interested in the impact on those who loved him left behind, and how they try to come to terms with the tragedy. We find out early on that David had moved out of the home about a month before Oscar disappeared as he and Miriam were separating, while later he is in a new relationship with life insurance agent Lorraine. Miriam’s older musician child Nancy (with her first husband Karl, now a reverend) is disturbed by what they believe may be Oscar’s ghost in their bedroom and contacts a paranormal society, then starts dating their investigator Mia. The younger daughter Margaret feels neglected by Miriam and after meeting an older man at the lido – nature conservationist Benjamin – becomes pregnant. Meanwhile Miriam’s behaviour becomes increasingly erratic.

Photo credit: Brinkhoff/Moegenburg.

There is an extraordinary scene where a sceptical Miriam takes part in a séance with Nancy and Mia who are trying to make contact with Oscar’s spirit, with Miriam ending up under the table groaning like an animal in pain. But there are many moments of humour too, even if sometimes it fits awkwardly with the sensitivity drama. An extended family party is alternately hilarious and uncomfortable, as Benjamin’s lengthy monologue about the declining world puffin population is punctured by an exasperated Miriam, while her hug with the gushing but well-intentioned Lorraine turns into assault.

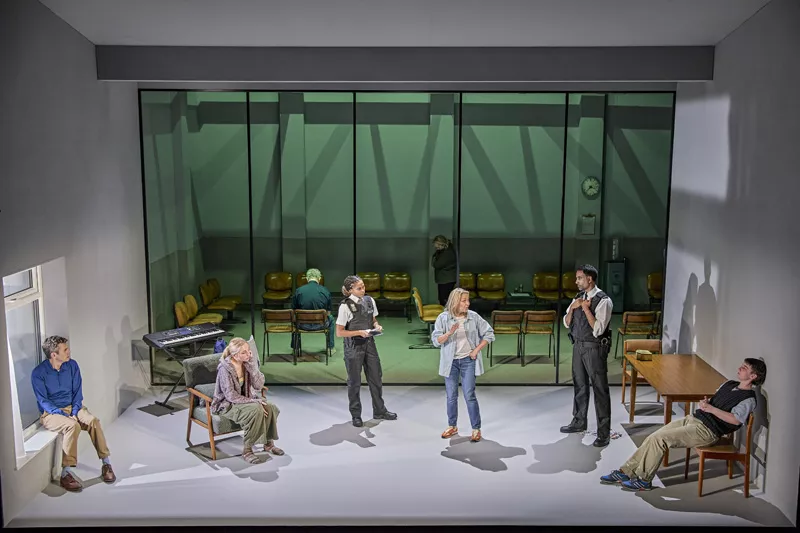

The transitions between scenes are seamless in Elliott’s slick production, with a time shift marked by the last line of the previous scene actually spoken in the next scene. Bunny Christie’s monochrome set is divided between the downstage family home and upstage what looks like an impersonal waiting room (police station or purgatory?) where actors not in a scene sit contemplatively in existential crisis. A single window stage left with an unknown view adds to the eeriness, with Jack Knowles’s lighting design making creative use of moving shadows to suggest passing time and Nicola T. Chang’s discordant sound signalling scene changes.

Nicola Walker is tremendous as Miriam, capturing both her passionate determination to find her missing son and the destructive effect it has on the rest of the family, in a rounded portrayal of abrasive provocation, emotional fragility, and barbed humour. Paul Higgins’s nervily unconfrontational David is a fine counterpart, with Alby Baldwin’s haunted, grieving Nancy and Ella Lily Hyland’s hurt, angry Margaret also impressing. There is good support from Martin Marquez as born-again Christian Karl, Lucy Thackeray as the warmly naïve Lorraine, Isabel Adomakoh Young as the spiritually inquiring Mia, and Harry Kershaw as biodiversity bore Benjamin.