“The Seagull” at the Barbican

Neil Dowden in central London

13 March 2025

Thomas Ostermeier, artistic director of Schaubühne in Berlin since 1999, has had a number of his productions staged in London over the years (including An Enemy of the People in the West End a year ago). But for the first time he has a created a show here, his fourth engagement with Chekhov’s tragicomic masterpiece The Seagull (as with the Ibsen, co-adapted with Duncan Macmillan). As you would expect from one of the most feted exponents of director’s theatre, it’s a radical re-working of this classic text featuring a starry cast led by Cate Blanchett and Tom Burke.

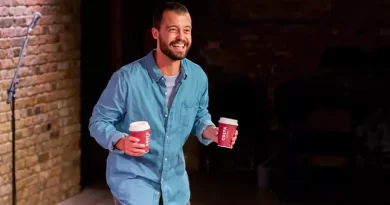

Emma Corrin and Kodi Smit-McPhee.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

We know it’s going to be different from the off when Simon (Semyon in the original) rolls across the stage on a quad bike, stopping and starting to comic effect. Acting as a sort of MC, he jokes with the audience (“How are you doing in the upper circle?”) before playing guitar while singing Billy Bragg’s selfless love song “The Milkman of Human Kindness”. (After the interval he performs the same artist’s long-suffering “The Man in the Iron Mask”.)

Simon – whose job has been changed from teacher to factory worker, presumably to ramp up class differences – is a drolly self-deprecating everyman figure whose feelings, like most of the characters in this play of romantic love triangles, are painfully unrequited. When the woman he loves, the even more dissatisfied Masha, arrives (and the play itself begins) she melodramatically declares “I am in mourning for my life” – perfectly encapsulating the melancholic absurdity that runs all the way through The Seagull.

Of course the initial breaking of the fourth wall – which occasionally recurs – takes its cue from this being Chekhov’s most “theatrical” work, with characters professionally involved in theatre as well as its play-within-a-play. The widowed actress Irina Arkádina returns to the family estate with her younger writer lover Trigorin, while her frustrated wannabe playwright son Konstantin stages his own new experimental symbolist play by the lake performed by the girl he is hopelessly in love with, Nina. He talks of the need for “new forms” to replace the conventional theatre he despises (and in which his mother has made a successful career). But his own work is pretentious and he goes off in a huff when the small invited audience – wearing VR headsets – do not pay it the respect it doesn’t deserve.

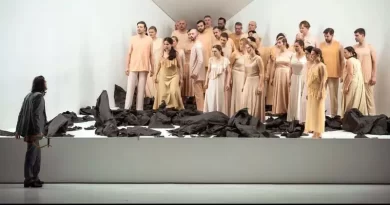

Tom Burke and Cate Blanchett.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Ostermeier makes it meta with the artistic discussion containing self-reflexive satirical comments about theatre that tickle the Barbican audience. They include a jest at his own expense as (echoing Konstantin) he once notoriously claimed, as the then avant-garde enfant terrible of German theatre, that directors over 40 should give way to youth (he’s now 56). There’s plentiful use of a microphone – also archly referenced – which many of the characters speak into at some point, though this seems rather random as sometimes they convey deep inner feelings while other times they are making public statements.

Ostermeier’s production accentuates the awkward comic moments and general sense of ennui in the play without becoming boring itself. At times it echoes absurdist theatre. The characters do tend to take themselves extremely seriously, each engrossed in their own private drama or playing a part they only half-believe in. Of course Chekhov’s compassion always shines through for these sad – if sometimes silly – people whose potential is often unfulfilled. Although some sense of poignancy does develop here, this is not the most moving account of The Seagull even if it is a genuinely fresh take on a very familiar work.

The audience is certainly embraced in the staging. A promontory – or perhaps jetty – sticks out into the stalls, with the auditorium becoming the lake while on stage a clump of tall reeds (Ostermeier’s regular designer Magda Willi) is used ingeniously for exits and entrances, as we see them quivering before people pop out.

Blanchett gives a bravely unsympathetic portrayal of the attention-seeking, sunglass-wearing Arkádina who is more prima donna than grande dame. (She also played Nina at Belvoir Street Theatre in Sydney in 1997, so similarly to the characters she has matured from up-and-coming to celebrated actor.) There’s very little maternal concern towards Konstantin whom she evidently finds an encumbrance and a reminder of her advancing years, while she’s both professionally and emotionally jealous of young Nina with whom Trigorin becomes involved. It’s also a very entertaining, energetic performance – fake fainting then grabbing a cushion to put under her head, even tap dancing and doing the splits, as well as raucously singing a few notes from Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry” – as an insecure woman who is always putting on an act, though occasionally it verges on the cartoonish.

Burke also gives an unusual interpretation of Trigorin – though this time more sympathetic than normal. Although he takes advantage of Nina’s naive aspirations (and later as we learn unforgivably abandons her in Moscow), he is portrayed as being weak rather than predatory, indecisive rather than cynical. It’s a somewhat muted, slightly underpowered performance, but interestingly it does suggest a self-involved man obsessed with writing who is doubtful of his talent and uses people as raw material for his oeuvre.

Australian actor Kodi Smit-McPhee is already well known for screen roles in the likes of The Power of the Dog and Maria, but he makes an impressive professional stage debut as the ill-fated Konstantin. He clearly has a love/hate relationship with his famous mother from whose shadow he struggles to emerge. Some of his sulkily impulsive behaviour may seem risible, but we come to believe that underlying his oversensitivity is a dangerously deep depression. Contrariwise, Emma Corrin’s Nina is more robust than the usual depiction of her as an innocent, fragile creature in flight – the seagull of the title. She is ambitious and though her dreams of becoming a great actress may not come true, you don’t doubt she will survive.

There is strong support from the rest of the ensemble. Tanya Reynolds is both amusing and touching as the goth-like Masha who resigns herself to marrying Zachary Hart’s good-hearted but all too irritating Simon. Priyanga Burford is her mother Polina who encourages her not to forsake romantic love, while having an affair with local doctor and ageing heartthrob Evgeny (Paul Bazely), while her husband and estate manager Shamrayev (Paul Higgins) however grumbling is dedicated to his employers. And Jason Watkins is very funny as landowner Sorin who cannot wait to escape the countryside back to the city, but whose fading health means that sadly he never makes it.