“That Face” at Orange Tree Theatre, Richmond

Jeremy Malies in west London

18 September 2023

Polly Stenham’s first play That Face (2007) opens by showing a piece of vicious torture (“bullying” would not cover it) in a dorm at an elite girls’ school. Private education, middle-class pretentions, gratuitous use of prescription drugs, and alcoholism are all put under the spotlight here.

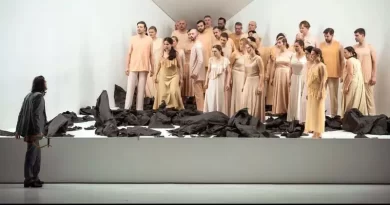

The ensemble. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

But it is poor parenting that Stenham (who wrote the play at the age of 19) truly skewers. Martha, played by Niamh Cusack, cannot find the strength of character to resist opening a bottle of wine or a pack of Valium even if the welfare of her children is going to be compromised.

Is the play an essay on bad parenting? Perhaps, but the malevolence in the first scene is surely nature not nurture. Stenham rightly makes the point that wisdom and restraint do not always come with age which should never be seen as denoting a rank. If you are going to say all this while still in your teens it helps to have prodigious technique which of course she does.

Martha thinks of her son Henry (played by Kasper Hilton-Hille, in his stage debut) as a soldier, addressing him as such and encouraging him to salute, but bizarrely she cuts every piece of clothing he owns into shreds so obliging him to put on one of her dresses which he sets off with a string of her pearls.

Quite why Hugh, Martha’s estranged alpha-male husband (Dominic Mafham excellent), does not even comment on his son looking like Tony Curtis in Some Like It Hot I cannot understand. “So, you like my new look?” asks Hilton-Hille who proves adept with Stenham’s many great gags. One of these is so good it deserves describing even if the explanation must be lengthy. In one of her inane rambles while clutching a bottle of plonk, Martha says that a gap year spent working in orchards means she has barely been able to face eating an apple since. “Shame you didn’t work in a vineyard” mutters Hilton-Hille.

The meaning of the title is unclear to me. Eleanor Bull’s design is more accessible; it features two illuminated hoops set above the stage and circular sweeps of whitewash on the floor. She and director Josh Seymour are, I believe, asking us to consider whether the parenting on view will be repeated in the next generation. Is this a generational whirligig? Will Larkin’s gloomy prognosis be endorsed or disproved? “They fuck you up, your mum and dad. / They may not mean to, but they do. / They fill you with the faults they had / And add some extra, just for you.”

Henry is disturbed that in this atypical environment, it is his mainstream behaviour and aspirations that are sneered at. When he beds (to the evident satisfaction of both parties) his sister’s school friend, his mother assumes that it has been a same-sex act of congress. Martha’s progressivism is such that by default she rejoices in this, saying that his gentle disposition had made her suspect his orientation. Stenham is puncturing this nightmare mother’s wokeness. Liberal she may claim to be but when it comes to sexual rivalry, she can still hurl racist epithets at Hugh about his new Hong Kong-based partner: “How’s it going with old slinky eyes?”

Henry’s girlfriend (played by Sarita Gabony) has another great gag. Surveying the results of the dorm torture and the probable death of a fellow pupil at her hands she is moved to say: “This is going to fuck up my UCAS!”

Stenham’s voice and material are in no way derivative. Just as you think we might be veering towards Streetcar with Martha’s psychosis or even Hamlet as she strews flowers around the bed in one of her mad scenes, the plot twists show that the writer is beholden to nobody.

There is an Oedipal element (though son would never have the physical strength to overpower father) when Martha insists on spending a sunny morning lying on a bed with her son while reading Lady Antonia Fraser’s biography of Marie Antoinette. Stenham reveres Antonia’s husband Harold Pinter, and it is the one influence that shows. Jamie Platt’s lighting design here is delicate as he depicts daybreak.

I wonder if my colleagues found the mother–son relationship curious, distasteful, or troubling. Is Martha simply misguided in wanting to make her son in her own image? I think not. The tone and drip-feed of information reminded me of Alan Bennett’s super-creepy An Ordinary Woman, one of his recent additions to the Talking Heads series in which he deals with incest explicitly.

I empathized in spite of myself with Mafham’s character Hugh (he smacks of New Labour) and his disdain for the posturing of this ghastly family. But Hugh is also a woeful parent who is so wrapped up in his new Hong Kong life that he has not even noticed that his son’s school reports have stopped. Stenham makes it clear that the way he berates his children contains no more thought than one of the weekly pep talks he gives to his brokerage underlings. But he does at least have a moral compass and is about to pay a fortune for Martha to attend a residential clinic with every chance that she will relapse.

Mafham and Cusack need only a few deft gestures to make themselves credible to us as a former couple. Given the age at which she wrote the piece, it is not surprising that Stenham captures teenage idiom so well, but the bickering between the parents is also convincing.

Seymour ensures that not a moment is wasted in these 135 minutes without an interval. Stenham and he progress the narrative briskly at one point by having two scenes run simultaneously as Martha and Henry loll on the bed while Hugh takes his daughter Mia (Bridgerton star and BRIT school product Ruby Stokes, also making her stage debut) to lunch. The director invests detail to great effect on painterly scenes such as Henry and Martha peering at one of his sketches and discussing how a view through glass will affect perspective.

Criticisms? The only carping can be purely factual. Hugh is said to have bought his daughter out of trouble at the school by paying for the installation of CCTV in the dorms. Ludicrous. Cameras in classrooms, be the school state or private, are frowned upon but tolerated if necessary. With the scope for misuse being so huge, recording in a dorm would be a criminal act. And even a hospital pharmacy would not have the quantity of Valium that Martha is downing like Smarties nor would theft of them by her daughter go unnoticed.

This is a brilliant, resourceful, and disciplined revival of a major play that will be performed decades from now without in any way being a period piece. Outstanding.