Ruth Walz, Berlin Theatre Photographer

An Exhibit in the Berlin Museum of Photography.

Dana Rufolo reflects.

I am grateful to Dr Ludger Derenthal, head of the photo collection department of Berlin’s Museum of Photography for a tour of the exhibit of the photos by Berlin-based theatre photographer Ruth Walz that ran from 8 October 2021 to 13 February 2022. There were over 500 photographs on exhibit, representing over five decades of professional photographs for the theatre and opera taken and developed by Walz. It is easy to praise as an exhibit but demands a more complicated response in terms of its underlying approach to the art of theatre photography itself.

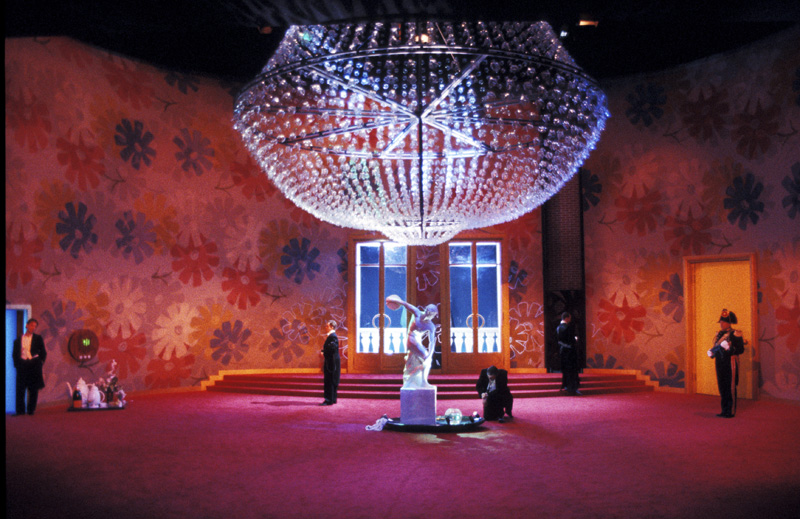

Splendid’s by Jean Genet at Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz, Berlin 1994.

L to r: Wolfgang Michael, Sylvester Groth, Peter Simonischek, Ulrich Matthes

and Thomas Thieme. Photo: Ruth Walz.

The collection of Ruth Walz’s photos contributes to the field of theatre photography that Plays International & Europe has always championed. During 2018, four currently active theatre photographers were interviewed by me for the magazine version that antedates the present digital version: Johan Persson and Marc Brenner in London, Laurencine Lot in Paris, and Iko Freese in Berlin.

These four are contemporaries, and although Ruth Walz still works as a photographer (she was born in 1941), her major contributions to the art form of recording the ephemeral moments of drama on stage were during the 1970s and 1980s when she was permanently associated with the Schaübuhne (then called the Berlin Schaubühne am Hallesches Ufer).

Photos from that era are invaluable for theatre researchers who concentrate on the work of German directors Peter Stein and Klaus-Michael Grüber as well as on international directors who were collaborators with Walz: Swiss Luc Bondy, Polish Krzystof Warlikowski, Americans Peter Sellars and Robert Wilson, Russian Dmitri Tcherniakov, and Italian Romeo Castellucci.

Dörte Lyssewski and Gérard Desarthe in Schändung by Botho Strauss.

Photo: Ruth Walz.

There are several rooms or delineated spaces in the exhibit dedicated to Walz’s work in relation to the playwright (specifically, various Shakespeare productions she photographed), scene designers or artists such as Jannis Kounellis, and specific actors and directors. Among these is the section of Walz’s photos of Peter Stein’s 1984 Oresteia (Die Orestie by Aeschylus) for the Schaubühne. There are even photos of the production in the amphitheatre located in the ancient Roman harbour, now an inland archaeological site, of Ostia Antica. That is because she travelled with the company when they toured. It is in fact her experience photographing Stein’s Oresteia that shaped Walz’s vision of the task of the theatre photographer. In the catalogue accompanying the exhibit, she wrote (translation provided by the museum) the following:

“In 1980, Peter Stein staged Aeschylus’s Oresteia at Berlin’s Schaubühne am Halleschen Ufer. Working on that production greatly impacted my concept of theatre photography and also broadened it. It has always been important to me that I not be an outside entity on any production, someone who solely captures the final outcome, but rather that I get involved from the outset and help shape the creative process as a participant observer.

Orlando by Virginia Woolf at the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz.

Jutta Lampe as Orlando. Photo: Ruth Walz.

“As I recall work on the Oresteia began with a piece of graffiti on the Berlin Wall, which I used to pass on my way to rehearsals at the old Schaubühne am Halleschen Ufer: “Durch Leiden Lernen” (“Wisdom comes through suffering”). Our own assistant directors had spray-painted this central passage from the Oresteia onto the brittle concrete of the Wall. This phrase, which at that time could well be understood as a political slogan, found its artistic equivalent in our rehearsals.

“At the beginning Stein assigned the entire ensemble the task of building a wall on the stage by hand in order—by way of physical exertion—to get into the spirit of the unfamiliar, mythical time of the play. From then on I was there for every step of the process, from the costume fittings on through the first stage rehearsals to the acclaimed opening night.

“One of the crucial photographic moments was the entrance of Clytemnestra (Edith Clever) after murdering Agamemnon. In order to capture the tremendous emotional tension built by Clever, I must have photographed that scene at least twenty times.

“My work on the Oresteia did not end on opening night. I accompanied the ensemble to performances in Rome, Athens, Caracas, and Warsaw. Then, in 1981, the Schaubühne opened its new space in the Mendelsohn Building at Lehniner Platz with Stein’s Oresteia. I remember setting up my Linhof camera in front of the building’s light-flooded glass façade to capture that historic moment. Later, I was also involved in ZDF Television’s documentary about the production, thus completing a process that had begun with a piece of graffiti on the Berlin Wall.”

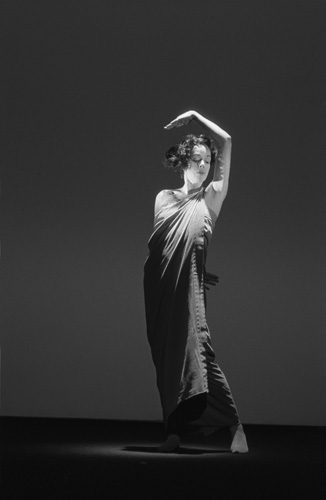

Erwartung by Arnold Schönberg at the Salzburg Festival.

Jessye Norman as One Woman. Photo: Ruth Walz.

It is Walz’s commitment to being present for the whole process of theatre production which was her most unusual trait as a theatre photographer. Her method of working stays in the memory of directors who worked with her. In an adjoining room in the exhibit, there is a video of three theatre directors talking about Walz: Robert Wilson; Peter Sellars, and the founder of north London’s Almeida Theatre, Pierre Audi. Wilson especially admired how she became a force in the shaping of his productions because of her willingness to give her own opinion about the show while she was present from the first rehearsals through to the premieres, and even, if there was one, the tour.

A placard reads that “Seen through the viewfinder of Ruth Walz … (a) bending leg, an extended finger, a shadow on the wall, a hand over the edges of the stage (are) warm signifiers instead of cold symbols, in harmony with programme booklets – not with advertising posters”. Indeed, Ruth Walz captured the vitality of theatrical moments even though she was then working with analogue cameras. Clearly, it was her way of attaching herself to a production as an active artistic personality and not just coming in during the dress rehearsal or previews, which gave her the advantage of intimate knowledge of the ebb and flow of dramatic moments in any given drama, permitting her to click the testimony to an ephemeral moment at precisely the correct moment of time.

Another emphasis in the exhibit is on her relationship to the playwright Botho Strauss. The German playwright Strauss (born in Saxony Anhalt in 1944) was a favourite of Ruth Walz; she systematically photographed productions of his work, and her portraits of Strauss range from 1974 until 2021. As well, the celebrated actor Bruno Ganz is well represented, with photos of him acting that range across his entire career. Ganz was Ruth Walz’s partner. He died two years ago.

The museum is not a commissioned edifice; on the contrary, 100 years ago it had housed two theatres according to a placard in the exhibit. The Neues Theater am Zoo was a private theatre that rented out its main hall to the office corps of the Landwehr after World War Two where it offered a mixture of operettas, comedies and plays until the effects of the Wall Street Crash put an end to its profitability. The hall was then taken over (1929) by Joachim von Ostau, an actor and singer, who renamed it the Deutsches Theater. Lavish plays with a national flavour were produced using prominent actors and actresses, but even so the economic situation proved untenable and the theatre closed in 1930. Nonetheless, the Berlin Museum of Photography reserved a room in the exhibit to the building’s theatrical antecedents in an effort to obtain more mileage out of this rare exhibit on theatre photography. The only other exhibit of its kind curated in Germany (Frankfurt) was about the Frankfurt photojournalist who worked incidentally as a theatre photographer, Abisag Tüllmann (1935-1996).

And this fact of the rarity of exhibits on theatre photography leads me to take up the theme mentioned in the first paragraph here, which is that there was no comparative perspective in the exhibit. Certainly, to have it observed that Ruth Walz displayed excellence as a theatre photographer because she captured moments of emotional intensity on film is to state the obvious. It is how Walz did so, especially in light of the technical limitations of the camera of the 1970s, which is interesting to know. Berlin theatre photographer and theatre photo collector Iko Freese said when I interviewed him in 2018 that when he worked commercially for Der Spiegel and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung after the excitement of German national unity in the 1990s while he travelled around Germany and German-speaking countries photographing theatre productions, he was not sent elsewhere because “they weren’t that much interested in what they considered to be foreign culture.” (PIE, Winter 2018, page 54). The absence of an international comparative context in the Ruth Walz exhibit suggests that the Museum of Photography remains entrenched in an insular perspective.