HG Matthews: An Appreciation

Crysse Morrison

A retrospective on my father, theatre critic HG Matthews (1893-1985)

In 1962 when I was 18 my father introduced me to Paul Scofield in the press bar of a London theatre after a show. “I never miss reading your father’s reviews” the actor told me gravely. I had recently seen him in that classic Peter Brook production of King Lear, and in my memory, he was wearing the regal robes of that part – which is clearly beyond unlikely, but the words I do know are correct because l wrote them immediately in my diary. They were etched on my heart anyway.

My father was one of the London reviewers for Theatre World, a glossy monthly publication covering mainly productions in the United Kingdom but with some European festivals included also. An A5 “quality” publication of around 60 pages, it featured black-and-white stage shots of the most talked-about new productions which, with captions, virtually told the story of the play like a graphic novel. There were reviews, biographies, and other more erudite features too, and Angus McBean took many of the high-quality photographs. HGM were the initials that showed which were my father’s reviews, while his articles carried his name as “Harold Matthews”.

A couple of months before the encounter with my stage hero, my father had written one of these longer pieces on the Royal Shakespeare Company season which featured Peter Brook’s direction, commenting: “Mr. Scofield’s Lear was admirably suited to this style of production. He was not particularly regal but was completely credible, while his eyes seemed grimly speculative and assessing, as his gravelly voice crunched on. One forgot what a burdensome part Lear is for an actor. Mr. Scofield did not seem to tire.”

Photo courtesy Crysse Morrison.

For my father, reviewing was a continuation of a lifelong commitment to drama. He had joined the team at the magazine soon after arriving in London in 1945, moving from Leamington where he had established the Loft Theatre and contributed to 42 productions as both an actor and a director. My own passion for theatre had been recognized and fostered early by my father, and throughout my teenage years I often travelled with him to London shows and sometimes also to Stratford-on-Avon and even Dublin and Edinburgh if he was reviewing these festivals for The Stage.

In Dublin we stayed at Buswells, a quirky nineteenth-century building in historic Molesworth Street which was converted into a hotel in 1923.I have a vivid and precious memory from 1965, when l had the privileged opportunity be at the Gaiety to see John Hurt in Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs. David Halliwell’s cult comedy about disaffected youth has been revived since and even filmed but, even more than in the film, John Hurt’s “pulverising, hysterically funny performance as Malcolm Scrawdyke, leader of the Party of Dynamic Erection at a Yorkshire art college” was the seminal interpretation, hailed in the actor’s obituary as the totemic performance of the mid-1960s.

As soon as l knew how to access the city’s theatres, l no longer needed to rely solely on press night tickets. ln those days — the early ’60s — it was quite acceptable for a teenage girl to travel alone on the bus for an hour’s journey through the suburbs of Brixton and Lambeth to London’s theatreland, and l loved striding through the streets at night, going on my own or with a school friend to the Old Vic where you could get “standing seats” for two shillings which allowed you to sit wherever there was a space, even if only on the stairs. Best, though, was to go with my father on press night, sitting beside him in the second row, stifling my excitement (“Critics don’t clap” he said on an early visit), absorbing the atmosphere, longing for the fire curtain to slowly lift and the play to begin. Here l saw Judi Dench in her first season playing Juliet as a stroppy thirteen-year-old, throwing herself on the floor in a tantrum of frightening rage when Nurse stopped her from seeing her new boyfriend Romeo (John Stride). Here l saw Franco Zeffirelli’s stunning set for Much Ado About Nothing, with fountains and ornaments in the garden coming alive and shuffling forward to hear Beatrice’s terrible whisper to Benedick: “Kill Claudio”.

Photo courtesy Crysse Morrison.

Looking through the few copies of Theatre World that l’ve been able to access, l’m struck by the amazing cavalcade of great actors and directors whose work my father experienced. This was a fantastic era for live drama, and legendary names abound in the pages of Theatre World month after month: Vanessa Redgrave, Laurence Olivier, Dorothy Tutin, Eric Porter, Robert Morley, Alan Bates, Peggy Ashcroft, Bernard Cribbins, Richard Attenborough, Jill Bennett, Frankie Howerd, Paul Daneman, John Gielgud, Anthony Quayle, Barbara Jefford, Laurence Harvey … During the 1950s and ‘60s, celebrated stage-trained actors were working alongside the film and television stars of the future.

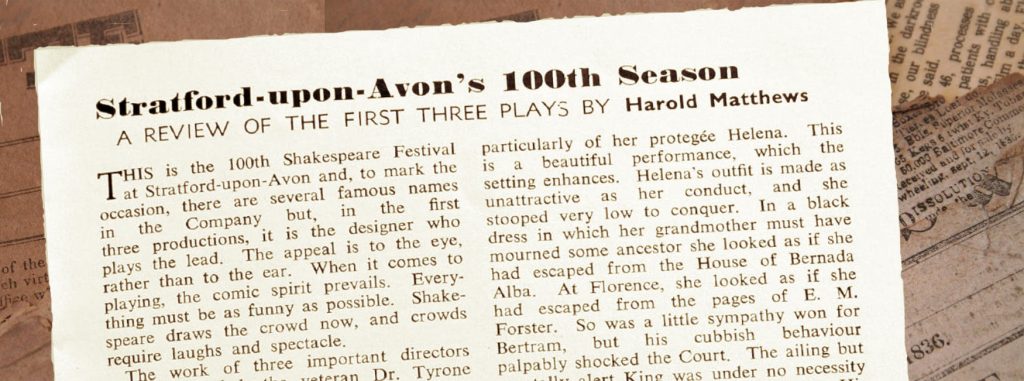

I have a copy of the July issue in 1959 which celebrated the Stratford-upon-Avon 100th Season which his readers must have been keen to attend. Three directors, all major names, took on three plays. Edith Evans, Robert Hardy, and Anthony Nicholls — all already film stars — took the stage for Tyrone Guthrie’s AIl’s Well and were approvingly reviewed: ”Anthony Nicholls was a crisp Lafeu. Parolles was delightfully portrayed by Cyril Luckham as a pretentious ass….The widow of Florence was also very amusing. Angela Baddeley, in fact, made her a perfect hoot.” Turning to Tony Richardson’s Othello, HG found “Paul Robeson’s organ notes were the most impressive feature” while Peter Hall’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream inspired his most unenthusiastic commentary: “The least uninteresting of the mechanicals is Bottom, because Charles Laughton plays him as a rather disreputable beach-comber …”

Much as HG loved attending the Royal Shakespeare Festival, he was never fulsome in his praise. He wrote scathingly of Eric Porter and Irene Worth as Macbeth and his lady in a “turgid, dismal and passionless” production by Donald McWhinnie in 1962, reserving praise only for Tom Fleming as a very drunken porter: ”The rest were muted, lukewarm and genteel”.

He could be caustic when unimpressed by a script. Reviewing a production of David Bird’s literary comedy Tom in 1957 he found nothing to commend this “dire” and “seemingly interminable rag”; concluding: “Hugh Dickson strove gallantly with the central part and, despite some embarrassing moments, one’s sympathies were with the company”. Damning with faint praise was another speciality of his, and he had a fund of anecdotes and put-downs by, and of, famous names in the world of stage.

Pencil drawing of H.G. when young by his wife Marjorie Ann Matthews, known as M.A.

Despite his preference for classic works, HG stayed in synch with the changing scene of drama and had genuine appreciation for “angry young men” like John Osborne and Arnold Wesker. I went with him to see The Caucasian Chalk Circle in 1962, the first professional production in English, at the Aldwych, and, knowing his respect for plays by writers such as Chekov, lbsen, Synge and Shaw, I was curious as to what he would make of it. (This was at a time when Bertolt Brecht’s name was not universally respected: Richard Burton told critic Ken Tynan in a public spat that his plays were “awful – pretentious, dull, pedestrian”.) My father was, as ever, interested primarily in the theatricality of the work. He reviewed the production as “very handsomely done, whilst at the same time director William Gaskill has been faithful to the Brechtian idea of anti-heroism” and spoke admiringly of Brecht’s “electric genius”.

HG’s views didn’t always chime with public opinion — or critical consensus either. When The Mousetrap opened in the West End at The Ambassadors in 1952, his private verdict was: “l give it a week”. I’m also suspicious of his review of The Hostage on its opening night in 1958, attended by its author Brendan Behan, which he deals with only briefly as “comical” entertainment: “lt’s good to see vaudeville come back in such fine fettle.” As HG was a huge admirer of lrish writers and writings, and well aware of the political context which underpinned the action, I suspect more than a dash of sarcasm in this short review. He wrote candidly of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, generally considered one of the finest plays of the twentieth century: “O’Neill pours too many words into his work”.

His outspoken reviews had their admirers, although HG never minded being accused of prejudice. ln his view, firmly-held personal opinions were something to be proud of. My father had seen two world wars take all his friends; his view of real life was melancholy. It was in drama that he found his joy and his voice, and I think he had learned to value speaking his truth however unpopular it might be. It’s all a reviewer can ever really do.