“Romeo & Juliet”: Shakespeare’s Globe

Jef Hall-Flavin on the South Bank

10 July 2021

Pandemic life has given us new ways of experiencing drama in our living rooms, but there’s nothing like the power of the theatrical event — a shared social experience around a stage — and Shakespeare’s Globe knows it. Like many, I approach Shakespeare with trepidation, having seen so many versions that fail to reach their audience, but Ola Ince’s Romeo & Juliet won me over right away. I’m not sure I’ve seen such a problematic succeed on so many level, and my visit to the Globe felt like a vaccination for the spirit.

Rebekah Murrell as Juliet. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

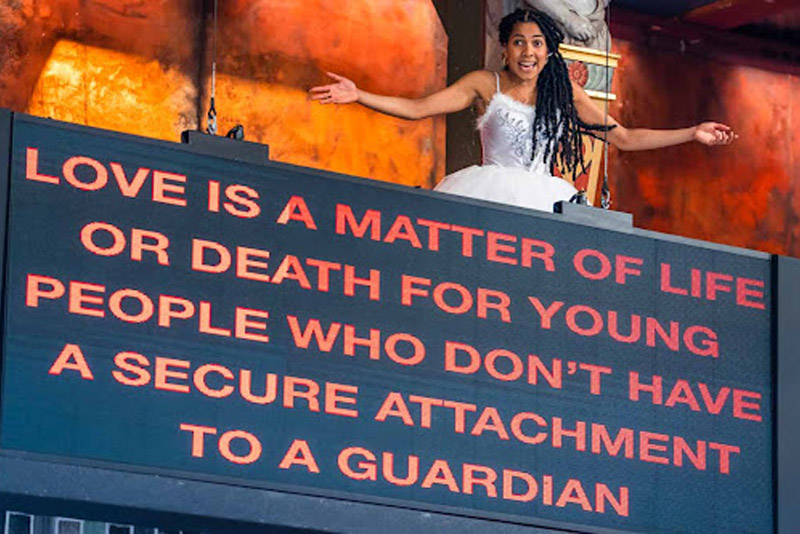

In an inspired opening sequence, the terrific cast and musicians introduced themselves and the roles they play, humanizing the proceedings from the start. Borrowing a handy technique used in Hamlet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the cast acted out a condensed version of the play in a dumbshow during the famous opening prologue, in which Adam Gillen (Mercutio) made fast friends with the audience, promising “two-hours’ traffic of our stage” — a promise faithfully kept with time to spare. Touted as a production that “finds new significance”, the most prominent feature of the stage was a large LED screen with block lettering, the text of which served as a thematic storyboard towering over the action, pointing out the societal ills of this modern-day Verona.

At first, I was thrilled at the bold decisiveness of the supersized supertitles: blood red, like the tight colour palette of Jacob Hughes’ thoughtful costumes. Each scene was given a thematic subject that contemporized the play, filtering it through an intelligent and effective societal lens. For instance, by shrewdly putting the Prince (Dwane Walcott) in a police uniform, suddenly Verona could be a Black Lives Matter Bristol or Minneapolis. Throughout. there was no question about the moral framework of this production in which poverty, violence, crime and punishment. patriarchy. disconnection. and other systemic forces are exposed on the screen as contributors to youth suicide. The supertitles succeeded in being a provocative, thought-provoking, and intelligently drawn commentary on today’s flawed society, reframing the 1597 worldview for a 2021 rethink. However, ascribing complicated human behaviour to a series of factoids quickly becomes problematic and reductive. A play is not a sociological thesis, alter all, and many of the thematic supertitles were at odds with the action.

Zoe West as Benvolio. Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

The cutting of the play was marvelous. At a running time of less than two hours, what was left of Shakespeare’s text was swift and impactful, and with few exceptions the obvious edits didn’t harm the story. The Capulet ball, however, was a brilliant mess. Staged as a kind of fancy-dress drug-infused rave with a mini-rock band, the scene went off-script and served as a drunken summary of events in the form of songs. Thank goodness the lyrics (written by someone other than Shakespeare) were projected above, because the band’s sound system made them impossible to hear. Juliet joined the band and sang into the microphone about her instant attraction to Romeo, and Romeo reciprocated in what seemed to me a major storytelling error. Did all the partygoers hear this love song, or was it just in the minds of the two lovers? The reaction of the crowd suggested that the secret love affair was no longer so secret, which kind of ruins the whole plot. Thankfully the party was saved by lovelorn Paris (Walcott) singing to unimpressed Juliet (Rebekah Murrell), hilariously intoning Lionel Ritchie‘s “Hello” in a shark costume. Suddenly the storytelling faux pas seemed less important.

As much as I applaud the supertitles, the characterizations of the main characters often failed to uphold them. The cast was blessed with exceptionally skilled and engaging actors, but Romeo (Alfred Enoch) with his “good vibes only” t-shirt and Juliet with her privileged antiseptic home life were not society’s victims, they were the most well-adjusted people on the stage. If that was a deliberate directorial choice, then I struggled to understand it. For instance, the supertitles suggest that young men are taught by the patriarchy that they aren’t allowed to feel, leading to peer pressure-induced depression. However, in a missed opportunity to drive this point home, Romeo seemed coolly above the fray of Mercutio‘s constant taunting. He seemed in complete control of his feelings, instead of confused, depressed, or insecure.

Alfred Enoch as Romeo and Rebekah Murrell as Juliet. Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

His friends Benvolio (Zoe West) and Mercutio seemed to have no actual sway over Romeo’s sense of self-worth in this production, though it would have been simple to position him as an easy target for Mercutio‘s toxic masculinity. If Romeo had fallen prey to Mercutio’s destructive brand of macho urban charisma that belittles feelings, I would have better understood the production’s societal assertions about the causes of suicide, especially in the urban setting awash with issues of race, class, and gender. This is just one example of several disconnects between the direction and the supertitles.

On the other hand, some pairings of supertitle and characterization were in sync, like when Juliet sends the Nurse (Sirine Saba) to fetch Romeo, and she gets mercilessly taunted by his gang of friends while the text above the stage read, “It is dangerous for women to go out alone.” Instead of laughing along with the naughty boys at the hapless Nurse, I saw the scene from her point of view, and the text reminded me of recent femicides and hate crimes in the UK, and the everyday fears faced by women in a male-dominated world. The clear feminist framework made the Capulet scenes leap out at me in new ways, rethinking the damage to a young woman who has no agency in her choice of marriage partner, no support from her mother, no advocate at home once the Nurse tells her to forget Romeo, and no adult attachments other than a reclusive Friar (who comes up with the ridiculous plan to pretend she’s dead).

Rehearsing and performing whilst in a pandemic is perilous (several West End productions have had to close temporarily because of COVID-19 outbreaks in the cast), so some of the production’s sharper edges were dulled by social distancing. Once the play starts, one quickly forgets about masks and temperature checks, but a benefit of the Globe is playing to a raucous group of groundlings on their feet, mingling in the yard. In this case they were “chairlings” spaced a respectable metre apart, unable to move —still less join in the fun of the Capulets’ rave. Half-way through the production it dawned on me that no one in the cast was touching, and even the most intimate of scenes were played from a metre apart – including murderous fights, death scenes, and conjugal lovemaking. No poison haply yet did hang on Romeo’s lips for Juliet to kiss, and that famous line had to be sacrificed. On the other hand, the pandemic happily cleared up what had always seemed a far-fetched plot point to me. The only reason Romeo doesn’t know Juliet is still alive is because a letter doesn‘t reach him in Mantua, and Shakespeare‘s explanation had always seemed too convenient to me, until now. Cleverly dressed in PPE and a plastic face shield, Fria John (Clara Indrani) explains blithely to the distraught Friar Laurence (Sargon Yelda) that they “Seal’d up the doors, so fearful were they of infection.” So, with Mantua in lockdown, I finally understand how authentic Friar John’s excuse really is.

In a long list of societal conditions that the production put forward, perhaps the most powerful was that suicide is the leading cause of death in all people under age 35. This grim UK statistic hung over the stage towards the play’s tragic ending emblazoning itself in my mind as Juliet unceremoniously blew her brains out. For this reason alone, and for many others, the production succeeded where many do not: I actually heard the play in a new way. The reductive dangers of explaining humanity through a neat lens were worth the risk in the end: it made me “Go home to have more talk of these sad things.” To me, this is what tragedy is for, and it was just the inoculation I didn’t know I needed.