“Minna von Barnhelm”, Deutsches Theater

Hans-Jürgen Bartsch in Berlin

31 January 2023

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s play Minna von Barnhelm was premiered in 1767 at a (now defunct) Hamburg theatre where Lessing worked as a dramaturge. It is a prose comedy that marks a deliberate departure from the then popular light comedies in the French tradition. Still today, it features regularly in the dramatic repertoire of German theatres. A highly imaginative version, created by Anne Lenk, who also directs, and the dramaturge David Heiligers, is currently showing at Deutsches Theater.

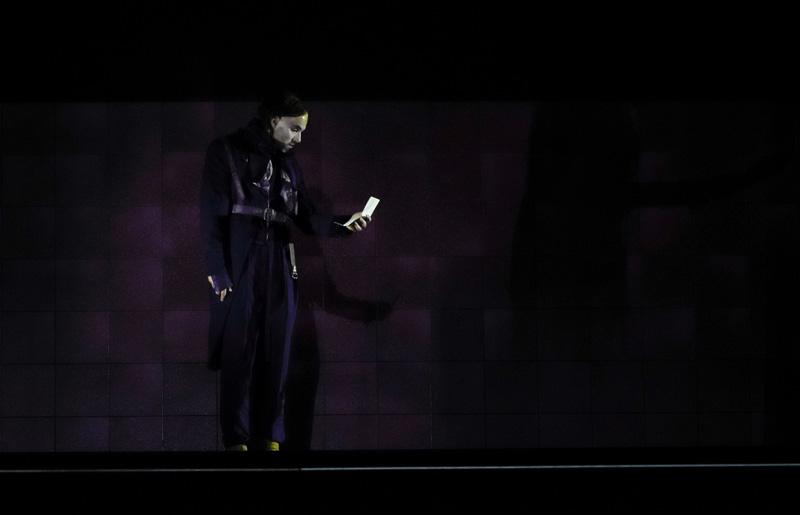

Photo credit: Arno Declair.

Written in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), Lessing recounts the tangled relationship of Minna, an aristocrat’s daughter, with her fiancé, the major Tellheim. Her predicament: the fiancé has absconded without taking leave of her. His predicament: he has been dishonourably discharged from the army, is consequently impecunious (“Peace has made me redundant”),and considers that self-respect and his (Prussian) sense of honour require him to renege on his promise to marry Minna. But he hasn’t reckoned with Minna’s tenacious efforts to track him down and win him back. Just in time for the final curtain, we (and he) learn that he had been rehabilitated, and nothing stands in the way of a happy ending. Minna’s perseverance and love have triumphed over the major’s old-fashioned bourgeois values.

The revival at Deutsches Theater is neither a conventional rendering of the original, nor one of the nowadays fashionable attempts to make the classics relevant for our times. Lenk and Heiligers have made but minimal changes to the original: they have cut the five acts down to a performance of under two hours without an interval, reduced the cast to six main characters, and adapted some of Lessing’s archaic vocabulary to contemporary parlance. Between the scenes, the rapper Fatoni contributes diverting intermezzi (music by Camill Jammal) that hint, with an undertone of mockery, at the relevance of Lessing’s narrative for our times, such as his allusions to the concept of honour in the military, the gender roles in society, particularly the plight of independent, self-confident women, the importance of capital (“A man who has to borrow money is not a man”), the glorification of the market economy (“You are a loser if you don’t participate in the market”), and the authority of the bosses over their subordinates – the masters and servants in the dramatist’s lifetime.

Photo credit: Arno Declair.

The setting for all the scenes is a lodging house in Berlin where Tellheim has found temporary refuge and where – what a coincidence! – Minna checks in one day on her search for the fiancé gone missing. Instead of a realistic replica of the house, Judith Oswald has designed a two-storey construction that extends over the whole width of the stage. It is divided into two dimly lit spaces, one on top of the other, resembling two large-size abstract paintings in an art gallery rather than rooms in a guesthouse. They are lit only while they are occupied – an ingenious device to do away with the interruptions needed for scene changes. And for the spectators the division into two separate sections has the advantage of getting to know Tellheim and Minna long before the two run into each other.

The costume designer Sibylle Wallum has dressed the cast in colourful fantasy outfits. Neither period nor modern, they are in line with Lenk’s staging concept, but in a centuries-old play these fairy-tale characters look odd even so. Equally curious is the idea to make the actors accompany Lessing’s dialogue with bizarre body language. While all that twirling, jerking, gesticulating and grimacing is impressive and quite amusing, it regrettably deflects attention from Lessing’s more subtle humour.

These reservations apart, Lenk’s inventive remake of this 256-year-old comedy is greatly entertaining, thanks above all to a team of enthusiastic actors: Natali Seelig as Minna, an assertive and self-confident early-day feminist; Max Simonischek as the (through no fault of his own) penniless major Tellheim who struggles to reconcile his ideas of manhood, pride and dignity with the liberal views of his moneyed fiancée; Bernd Moss as Tellheim’s grumpy, but loyal attendant; and Jeremy Mockridge as his former batman and now a friend who recovers debts and negotiates loans for him.

Photo credit: Arno Declair.

As the landlady of the lodging house (a landlord in the 1767 original), Lorena Handschin reveals the different facets of her character: avaricious, impertinent, slightly mischievous, but also quick-witted, this single woman raises two orphan children, victims of the recently ended war. She is in dire financial straits, which explains her greed for money. Although she feels empathy for Tellheim and shows it, she has no scruples about moving him from his upper-class room to modest upper-floor quarters, when she needs to accommodate Minna, who is clearly a better-off client.

Seyneb Saleh as Minna’s maid Franziska – more companion than servant – gives a (not only in the figurative sense) towering performance: she struts about the stage on stilts (possibly over-long stiletto heels), which makes her stand out from the rest of the ensemble not only as the tallest player, but – as we quickly realise – also as the comedy’s leading lady. She may walk on stilts, but her behaviour is anything but stilted. She is self-confident, cheerful, spontaneous and easy-going, and has a fine sense of irony. Saleh’s brilliant performance is the more impressive as she replaced an indisposed colleague at very short notice, just before the premiere.

Franziska falls in love with Tellheim’s former batman Paul Werner and the two join their masters in the celebration of a happy ending. Typical of Lessing’s dry humour, the comedy ends with Werner telling his future bride: “In ten years you’ll be a general’s wife or a widow”.