“Jacob Storms’ Tennessee Rising”, Edinburgh Festival Fringe

Jeremy Malies in Edinburgh

10 August 2023

There are two shows about Tennessee Williams in the city but no productions of his plays. I chose to watch this one-person piece by Jacob Storms which begins with our man on the cusp of his career and in New Orleans.

The monologue (also written by Storms) didn’t answer any questions for me. I felt no nearer Williams’s muse, the main themes of the writing or indeed the torments which he described as his “little blue devils”. Storms subjected us to abrupt clunky quotations from the work and I counted no less than three references to “the kindness of strangers” delivered as though we were being given something insightful. You would have to suppose that every audience member was soaked in the work. Indeed, a gentleman near me mentioned (with modesty and a self-effacing quality) that he had met Williams while producing one of the plays. We all deserved better.

There were interesting moments in our man’s reflections on his contemporaries, notably D.H. Lawrence’s ghastly wife Frieda and her maxim that the sensual and the spiritual should never be at odds, a piece of advice that Williams certainly observed. Storms was impressive as he showed us how the writer became emboldened while exploring the confines of his imagination. But when the script does not rely on snippets from the playwright himself it is leaden and cliché-ridden. A female friend has “eyes like a cat”. Hmm! You have to think that Williams himself had more in his lexicon.

There are some highpoints. Storms captures the waspishness when discussing Laurette Taylor’s initial notions of a Southern accent: “Dialect she has acquired from Porgy and Bess”. When he is observing a tethered iguana, I could sense the writer’s cogs whirring and as he considers the threat of fascism (“the very definition of mendacity”) you could feel his gorge rise. Similarly, as Williams thinks back to the impact of the great Russian actress Alla Nazimova in the 1932 premiere of Mourning Becomes Electra we get an understanding of how he would devote himself to the stage and create notable female characters.

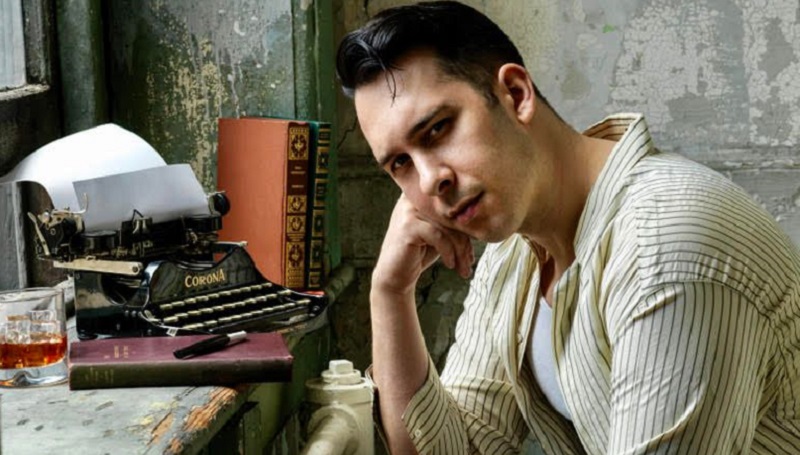

Tennessee is shown with a Corona portable typewriter and a bottle of spirits in the room of a boarding house. Physically, Storms is credible as his character. But his clothes are disappointing to the point of being slovenly. I doubt if Williams would have so much as popped out to a corner shop without a knife-edge crease in his shirt.

“A terrifying knowledge of the secrets of the mind” was contemporary New York critic Brooks Atkinson’s summation when asked to identify the Williams gift. I didn’t feel the man was being conjured up with few secrets being revealed and scant insight on show. I had hoped that an emotional gearbox would be explored. The play ends illogically and abruptly (ostensibly this portion of the career has been the creative dawn) in 1948 as the film version of The Glass Menagerie is being cast and Jimmy Cagney up for the part of Tom. Now that would have been interesting!

“We have not long to love” is one of Williams’s own poems and it is as insistent about the transience of love as the poetry of Andrew Marvell. At 60 minutes this encounter rarely felt transient.

.

.

~