“Cuckoo” at Royal Court Theatre

Neil Dowden in west London

19 July 2023

Michael Wynne’s new play Cuckoo – his eighth for the Royal Court which includes the Olivier Award-winning The Priory – is an intriguing dark comedy that doesn’t quite make the most of its potential. Unusually for a male playwright, it features only female characters in a domestic drama set in Wynne’s hometown of Birkenhead in Merseyside, with the humorous colloquial dialogue fully convincing. But the jump from slice-of-life naturalism to portentous allegory doesn’t carry the same conviction.

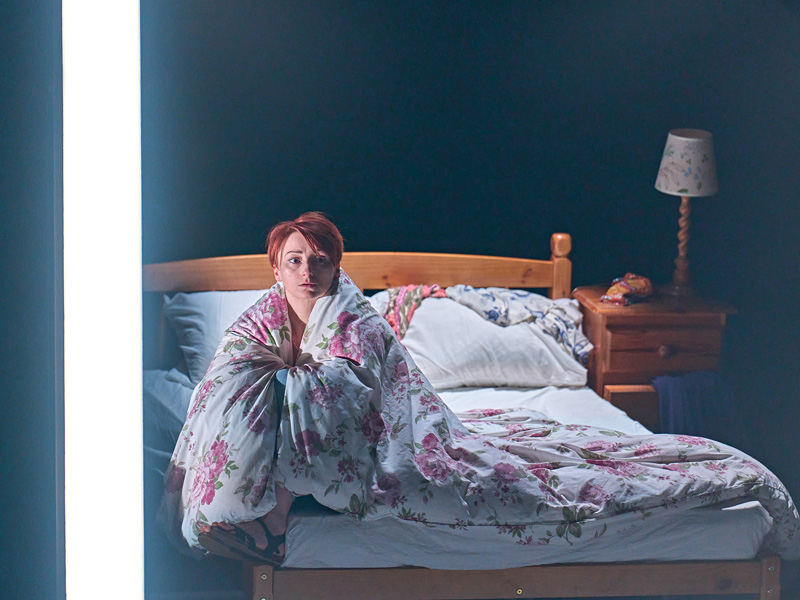

Emma Harrison as Megyn.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Cuckoo starts off in low-key, sitcom-like style with a fish-and-chip supper in the home of Doreen who is with her two grown-up daughters, Carmel and Sarah, and Carmel’s 17-year-old daughter Megyn. Initially, they are all too preoccupied with their mobile phones to speak to each other, but when they do the tensions become clear within this close-knit family who do not communicate well with each other.

Doreen – a widow for four years – is busy selling off her late husband’s stuff and other old family bits and pieces on an eBay-type website much to the chagrin of Sarah in particular who idealizes her father and who feels her childhood is being dismantled. “I’ve got me own money at last to do what I want with,” Doreen proclaims. Moreover, it seems that she is moving on with a new romantic attachment online that she has kept secret from her daughters.

After previous bitter disappointments via dating apps, primary school teacher Sarah is now seeing a dentist with “lovely teeth” and has put down a deposit for their holiday to Cuba – but will he be the one? Her older sister Carmel, meanwhile, is “done with men”, after her husband has abandoned her and Megyn, leaving her to struggle financially now as a zero-hours contractor for Boots.

Furthermore, Carmel is struggling to cope with her depressed daughter who has just finished school with no exam passes and who has withdrawn into a virtual world without friends: “She’s got two thousand online but in reality, none.” Megyn seems beset by fears, saying fatefully, “If we don’t act now the world is going to end.” But when she suddenly breaks down in tears and runs upstairs into her grandmother’s bedroom – where she takes sanctuary under the duvet for weeks while messaging for food to be brought up to her – it is unclear why. Is it the climate crisis, or other frightening events going on in the outside world? Or is it something more personal, perhaps involving abusive relationships?

Jodie McNee as Sarah.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Wynne makes the relations between the four women entirely believable, with the two sisters bickering familiarly, Sarah giving unsought-for advice about her niece, as Carmel loses her patience and temper with Megyn, who retreats more into herself as a means of passive aggression against her mother, while Doreen acts as general peacemaker though for the first time starting to assert her own independence.

But although there are interesting references to the impact of ever-present cyber culture on family life, the way social media can distort the way people connect with each other, and how news flashes about terrorist atrocities or human disasters can become a voyeuristically distancing experience, there isn’t enough substance in the play to give it a wider impact. However, there’s a clever twist at the end that points to the dangers of isolating ourselves from reality.

The assured production by Vicky Featherstone – in her final season as artistic director of the Royal Court after ten years – is always watchable. Peter McIntosh’s realistically detailed design of a conventional dining room with glimpses of the kitchen and garden gives way to an unexpected, final coup de théâtre. Jai Morjaria’s surround lighting effects and Nick Powell’s electrical sound pulses suggest an invasive digital world.

The cast all give engaging, persuasive performances. Sue Jenkins is amusing as the matriarch Doreen who has always put herself second to the needs of her family embracing the freedom of a late second lease of life without being controlled. Jodie McNee is touching as the up-and-down Sarah whose hopes are continually dashed, while Carmel’s world weariness offset by cynical humour is deliciously conveyed by Michelle Butterly. And Emma Harrison does well in her professional stage debut as the anxious Megyn addicted to her smartphone who becomes a cuckoo in the nest of her grandmother’s bed.

.

.

~