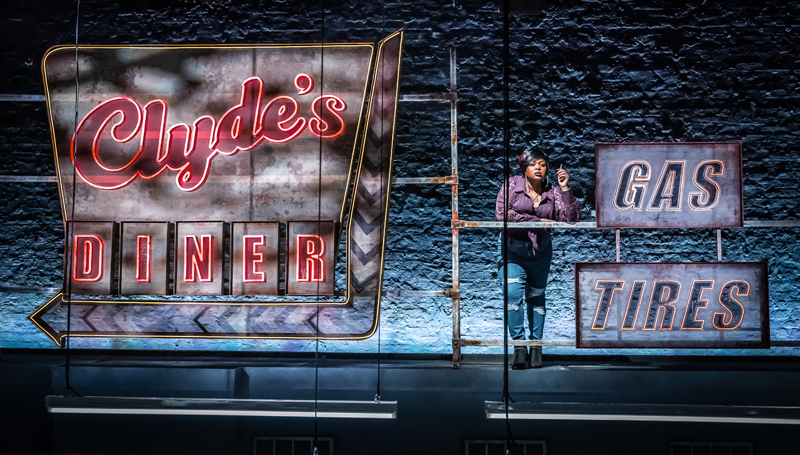

“Clyde’s” at Donmar Warehouse

Jeremy Malies in the West End

29 October 2023

Worker solidarity, second chances, and ambition tempered by kindness are the themes running through Lynn Nottage’s 2021 play Clyde’s. This double Pulitzer Prize winner’s work has been seen recently on the West End in The Secret Life of Bees for which she wrote the book to accompany lyrics by Susan Birkenhead. Her range of inspiration and concerns has been underlined by the Kiln Theatre’s recent production of Mlima’s Tale about endangered elephants.

The cast with Gbemisola Ikumelo as Clyde in foreground.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

This is a workplace drama but don’t expect any trite conversations around the water fountain. The setting is a roadside layby sandwich shop (I don’t think it is even sit-down) for truckers on a bend of Pennsylvania’s Delaware River. The characters are the kitchen staff, all of them proud ex-cons who have goals that will not allow them to watch their lives slip away. Orbiting them is Clyde, the proprietor played by Gbemisola Ikumelo, who has also done time. She is tough but only marginally more astute than her workers. Clyde is in debt to Mexican criminals for the fresh produce and has been pressurized into laundering their money.

Ikumelo also has a career as a comedian and director Lynette Linton renders each of her entrances a spontaneous comic turn as this scary gaffer orbits the staff, polices their every move, and subjects them to put-downs. She is the employer and that is the extent of her generosity. Tension grows as staff risk her wrath when idling or using her ingredients to design their own sandwiches. But as the beer-swilling Ikumelo stands alone at the top of Frankie Bradshaw’s two-tier set, we realize that her demons are as real as those of the more desperate and flawed characters.

I can’t readily remember a play with less seeming artifice: Linton ensures that the plot develops seamlessly from barbed combative exchanges that appear to have little weight at the time but impose a structure. Each character is goaded into designing a spectacular sandwich for evaluation by their peers, the crucial judgements on these coming from the senior shamanic employee Montrellous (Giles Terera).

Sebastian Orozco as Rafael.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Failed bank robber Rafael (Sebastian Orozco) assembles his signature turkey sandwich as if he were sculpting or creating a Ming vase. “The sandwich is your pulpit, it’s where you preach the gospel of good eating.” Later, each character gives a lyrical declaration of how they ended up behind bars. In less astute hands this would be formulaic but it brings Nottage and Linton to a tidy resolution that they earn. The section ends with Montrellous describing how a non-complicit drug mule was duped.

Terera has played Othello recently but don’t think this role is a walk in the park or beneath his talents by comparison. Conveying Montrellous requires him to exude a Zen-inspired serenity that borders on majesty. In the account of his arrest, he spins the mood of the theatre on a dime and you could sense audience members wanting to cry out such was their anguish. Nottage is adept at making us visualize offstage characters such as the handicapped daughter of an employee who must spend much of her pitiful wage on childcare.

Despite the descriptions of prison violence and the grinding poverty (Jason portrayed by Patrick Gibson is sleeping rough and asks for an advance so he can put fuel in his vehicle) the play never takes itself too seriously. When characters scream ridiculous advice such as telling each other not to “disrespect the lettuce” the text should be taken literally but comic elements lurk. Gibson (something of a Nottage specialist having appeared in Sweat also directed by Linton at the Donmar) must have his character, the only Caucasian, convince colleagues that his white supremacist tattoos were not a willing choice but the result of prison yard intimidation. That’s a big call to which his prodigious technique rises. Gibson stands out even in this elite company.

Gbemisola Ikumelo as Clyde.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

The garnishing of sandwiches becomes a frantic ballet (movement director Kane Husbands). All are involved in a dance to keep ahead of the orders from the pass-through window which Bradshaw’s set makes realistic. The most magical moment of an evening with many high points sees the cast slide food preparation stations around on their castors with lighting designer Oliver Fenwick illuminating the silicone cutting boards such that they become phosphorescent. Textual notes ask for subtle shifts in colours throughout and Fenwick manages to have the neon tubes of the signs advertising the cafe radiate every conceivable shade of crimson. Earlier, stage directions have asked Fenwick to make a grilled cheese sandwich glow which he somehow manages.

Any criticisms? The cooking smells, for me at least, brought on a queasiness and the thought of a peanut butter sandwich with grape jelly made me retch. But I had recovered my appetite at the end of the evening only to find that the exotic menu at Clyde’s made the sandwiches on offer at Marks & Spencer within Victoria Station look tame. It was a wonder to me that the cast could act while making intricate sandwiches with real ingredients using sharp knives. As Letitia (Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjo) diced up peppers without looking, almost as a reflex action, I nearly broke the spell by cautioning her to be careful.

Influences or similar outlooks? Nottage’s is a unique voice; you don’t win two Pulitzers for being derivative. But in broad terms think Marina Lewycka as a novelist working in a similar vein. The final scene smacks of Clifford Odets’s Waiting for Lefty but without the class struggle.

With the possible exception of debbie tucker green, you will not find more naturalistic dialogue being performed in the UK unless it is verbatim theatre. This wonderful play underlines Nottage’s conviction that drama should emerge primarily from lived experience and have few other reference points. Her structures are never contrived and the themes are accessible. Clyde’s illustrates her social conscience and ability to tackle issues such as career prospects after a jail term without a hint of preaching or agitprop.