“Christmas Day” at Almeida Theatre

Jane Edwardes in North London

★★★★☆

19 December 2025

To start with the set. Designer Miriam Buether has excelled herself in designing an unwelcoming, brutal bunker. It’s semi-industrial but not remotely chic. The brick wall is covered in peeling white paint. There are flimsy doors, metal tables, and an excess of pipes and plugs. And most prominent of all a huge industrial heater is suspended from the ceiling, which periodically bursts into thunderous life. That is compounded by the sound of the Northern line trains that rumble underneath. To get us in the mood we even enter the theatre through a temporary decrepit passage.

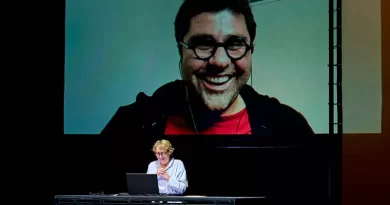

Set design: Miriam Buether.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Sam Grabiner, who won an Olivier Award for Boys on the Verge of Tears, has written a challenging, uneasy, and often startlingly funny play about Jewish identity, about the different feelings within one Jewish family, particularly in the wake of the October 7 attacks and the war that has followed. Plays written in the heat of the moment can often be crudely simplistic, but Grabiner has an elliptical take as he brings his characters together on Christmas Day for a meal that combines a Chinese takeaway with plenty of argument and occasional references to Christmas traditions. Christmas jumpers and crackers can both spark debate. The decorative touch of a Christmas tree down left and fairy lights above hardly relieve the gloomy atmosphere. Nigel Lindsay’s bullish Elliot is seen studying the tree at the start, reflecting that “there’s something perverted about a Christmas tree”, claiming they have “a malicious kind of an aura”.

Elliot’s presence is a surprise to his daughter Tamara, who is not all that pleased to see him. She, her brother Noah, and his non-Jewish girlfriend, Maud, plus ten others, all live in this ex-office block. It’s a long trip to the lavatory. The others, except for stoned Wren, who wanders through occasionally minus most of his clothes, have gone away for the holiday, and Noah has booked the living space exclusively for his family party. In addition to Elliot, Aaron (once Jack), a childhood friend of Noah’s and ex-boyfriend of Tamara’s, is due in from Tel Aviv.

Sporting a Christmas jumper, Elliot is not impressed by the living quarters. Is it a squat he demands? He is appalled by the noise of the heater and by the number of people living there. His attempts to keep up with the zeitgeist – critical race theory and personal pronouns – irritate his children. He and Noah both react violently when other people creep up behind them as if it is part of their genetic inheritance. Elliot has a partner, Sarah, a New York Jew who is disliked by both Noah and Tamara, which could explain why she doesn’t come with him.

The most articulate of the group is Bel Powley’s sharp-witted Tamara. She brings all the weight of Jewish persecution and pain to the table, much to the embarrassment of the other Jews. Sick of being the “bad guys”, she wants Jews to ally themselves with all oppressed people. She and Noah share the news that something horrific has happened, although we never discover what. Powley’s round eyes express both Tamara’s vulnerability and aggression as she attacks Jacob Fortune-Lloyd’s easy-going Aaron who has decamped to Israel escaping “that-not-quite-belonging-thing” in England and where he appears to feel cool with all that is happening. It is Elliot, however, who is the biggest defender of Israel, thumping the table as he declares that the country is “OURS!”. Controversially he claims that the Palestinians had their chance at Oslo and blew it. It is left to Callie Cooke’s kindly Maud to throw in the occasional irrelevant comment.

If all this sounds very schematic, it doesn’t feel like that in the theatre. James Macdonald’s immaculate, strongly cast production is hugely helpful, steering one’s attention from one character to another. The pacing is reminiscent of Annie Baker’s work or David Adjmi’s Stereophonic. Arguments flare up and then die down again. There is a long period of silence while they all eat the meal. But as the play develops, the revelations pile up and it becomes increasingly symbolic. Problematically, one is not quite sure what it is symbolizing. What is the meaning of the near-dead fox that stoned Wren (Jamie Ankrah) brings into the room, and why does Samuel Blenkin’s appealing Noah smear himself in its blood which is then washed down by Maud? At this point it feels as if Grabiner is searching for a climax that isn’t organically there.

It’s not exactly Christmas fare. But then plays set at Christmas rarely are. Its power is inevitably heightened by the rise of antisemitism and the recent attacks on the Manchester synagogue and Bondi beach, and it will surely have the most profound effect on a Jewish audience. The play is full of interesting ideas, and surprisingly even-handed in its presentation of the very different views that are presented onstage. One feels as if the family will just about hold together, despite their many differences. It’s a compelling evening: the acting is terrific, and Grabiner marks himself out as a playwright of note.