Phyllida Lloyd interview

British director Phyllida Lloyd has set three Shakespeare plays in a women’s prison, book-cased another (The Taming of the Shrew) with a beauty pageant compered by a Donald Trump-inspired figure, and conceived Wagner’s Brünnhilde as a suicide bomber. In this interview, she talked to me about her experiences of directing Shakespeare, Schiller, and Wagner; how workshops with prisoners can find routes into new interpretations of a story; whether recorded theatre can ever truly capture the essence of a production; and the challenge of bringing young people to opera – a form in which Lloyd has worked extensively and is highly respected.

One’s view of the crown jewels of literature (her own phrase) will often be tested in a Lloyd production, but you will always be challenged and never bored. Lloyd has a new film out, Herself, starring long-term collaborators Harriet Walter and Clare Dunne. Its themes touch on domestic abuse and one woman’s struggle to find safe accommodation which have become topical issues during Covid lockdown. Predictably, Lloyd proved good company when I spoke to her over Zoom.

Phyllida Lloyd interviewed by Jeremy Malies

Shakespeare in the Park is a major item on the New York cultural calendar. It was founded in 1954 by Joe Papp and came of age in 1956 when the dean of American theatre critics, Brooks Atkinson, ventured downtown to review The Taming of the Shrew for The New York Times and wrote a rave review of a production directed by the traditionalist and textually obsessed Stuart Vaughan in which Atkinson saw “the Renaissance tempo in Shakespeare’s writing with an extravagance of phrase and action”.

Exactly sixty years later, the same venue (now known as the Delacorte Theater) opted to stage The Taming of the Shrew again and asked Phyllida Lloyd if she would like to direct. When the offer of the gig came, she was warned by veterans of the 1,800-capacity space to expect disruptions ranging from mosquitoes to racoons, low-flying helicopters headed for Long Island to rainfall resembling a monsoon. It’s not only a challenging venue but the play is one of Shakespeare’s most problematic with a treatment of sexual politics that can strike many as distasteful. Not once did Lloyd shy away from the play’s themes of manipulation and violence, with the tagline “Love’s a battlefield” featuring in the publicity blurb. Her first piece of inspiration was to replace the original’s clumsy tavern framing device with a beauty pageant that acted as a springboard for the narrative. There was a clear suggestion that life for many women in a patriarchy does indeed have the unsavoury nature of a pageant, and this was reinforced by the depiction of forced marriage and psychological manipulation. Lloyd’s trademark self-awareness could be seen in myriad details including a minor character complaining that a play of this kind should never be directed by a woman.

Lloyd is best known to current British theatre audiences for her ground-breaking Shakespeare trilogy at the Donmar Warehouse: Julius Caesar, The Tempest, and the first part of Henry IV with the rejection of Falstaff included to make it clear there would be no part two. All three shows transferred to St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn between 2013 and 2017. (Our images here by photographer Pavel Antonov are from the New York run and were kindly supplied by Blake Zidell & Associates.) “Release” and “disturbance” are recurring words in her vocabulary, and it’s obvious that whenever she accepts an assignment (or rejects one) her criterion is whether she can release a text from the page to make it relevant and vibrant. She says, “You can have multiple university degrees and still be very dull on stage with Shakespeare.”

Phyllida Lloyd’s 2016 production of The Taming of the Shrew began with a beauty pageant. Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

Inevitably during Covid-19 lockdown, our talk turned to streamed and recorded performances. I’ve just watched her Shakespeare trilogy in recordings provided by Marquee Theatre, having been something of a super-fan of the original stage productions and going frequently to matinees where I was often surrounded by rapt curriculum audiences. I confess that with the exception of Julius Caesar, the recordings haven’t exactly hit me in the solar plexus. Lloyd is disarming and candid. She agrees that only the recording of Julius Caesar really works and says, “Other people have put it more elegantly than me, but theatre on screen is like glossy food photography with a huge gap between representation and the real experience. There’s a contradiction for me; it’s either theatre or it’s on screen. It’s either being performed for a theatre audience or it’s being performed for a true cinema or television viewer. I struggle with this and always have done. There is a whole other conversation about use of the word ‘capturing’ theatre. I resist the notion that theatre can be captured.”

So why does Julius Caesar indisputably work on screen? “Because the audience play their part when required, even though it’s made explicitly for a screen-viewing public. I shot in the round like a movie, getting in over the actors’ shoulders, while most theatre shows are shot from the auditorium. When Brutus (Harriet Walter) and Cassius (Martina Laird) talk to each other, you’re looking at them from two different nights. But what you’re getting is the camera being right on the eyelines of both. With the audience being there you couldn’t have had two cameras working on the same night. It succeeds because, say, the camera is pointing at Harriet and the audience are behind her, I manage to get the audience to disappear when I want. And of course, the audience is very much in evidence when we go into the forum with Caesar (Jackie Clune) and you see them all and think ‘Gosh! We’re now in a big parliament.’”

It’s a striking feature of the trilogy done at the Donmar that all the actors use their normal accents. I ask about the rehearsal process and how Lloyd works with performers on the verse. Does she (as an opera director as well) hear the verse like a musical score? Is it collaborative? My guess is that she doesn’t have Peter Hall’s trademark insistence that every line should receive an exact stress, but there may be some rigorous requirements.

“I think I’m just as obsessive about textual detail as Peter Hall was though the approach may be different. First of all, each of those actors, notwithstanding whether they had any Shakespearean experience before, was chosen for their instinct for it. And the people who found the most direct route to the meaning often had little formal education. I work in a free but also forensic way. We analyze the detail of the text – the value of consonants and vowels, making vowels always long, consonants always precise. We mark changes of thought − the handing of the baton from one actor to another, always giving the actor who picks up the baton a strong point of exchange with the last word.

“Everybody understands each other’s speeches − we paraphrase the verse and discuss it at length. Then there’s a period of exploration where we improvise so we’re not speaking Shakespeare at all but are working with a detailed knowledge of what the text means. We’re following the changes of thought that Shakespeare uses but all in our own words. Accent is irrelevant to me. It’s about vowels and consonants − whether your vowel sounds are in broad Glaswegian or an Irish brogue. And we know Shakespeare’s vowel sounds were different. The accent spoken at that time was markedly different to BBC Received English. If you try to add an extra layer with another accent − telling an actor who is naturally Glaswegian that when they start Shakespeare they have to use Received Pronunciation − then you’re further distancing them from the text.”

As Lloyd continues, I get a sense of the exhilaration that must build as arduous rehearsals produce results and early run-throughs of a play begin to take flight. I’m also catapulted back into the immersive experience of seeing the productions at the Donmar, with ushers doubling as prison warders and proving reluctant to come out of character for anything other than an unusual request from a theatre-goer. “These actors close the gap between themselves and the text in the way that outstanding musicians become one with the score. When Clare Dunne is on stage as Portia you would think she was having these ideas as she speaks. It’s always about making the audience believe that thoughts and events are taking shape in front of their eyes.”

“I think I’m just as obsessive about textual detail as Peter Hall was though the approach may be different.” Phyllida Lloyd

I ask Lloyd about the interruptions in the plays when the prison guards burst in and bring the action to a close. “My colleagues and I were trying to get close to the level of tension and disturbance that must have been in the audience when these plays were first performed in Elizabethan England which it should be remembered was a virtual police state. Remember that the original audiences are standing there, not in period costume but what was modern dress for them as you and other theatregoers were when you attended the trilogy. We only used vestiges of period props: a fragment of Roman armour or a rudimentary medieval crown made from tin cans. This is more like watching Hamilton than it is a period production.

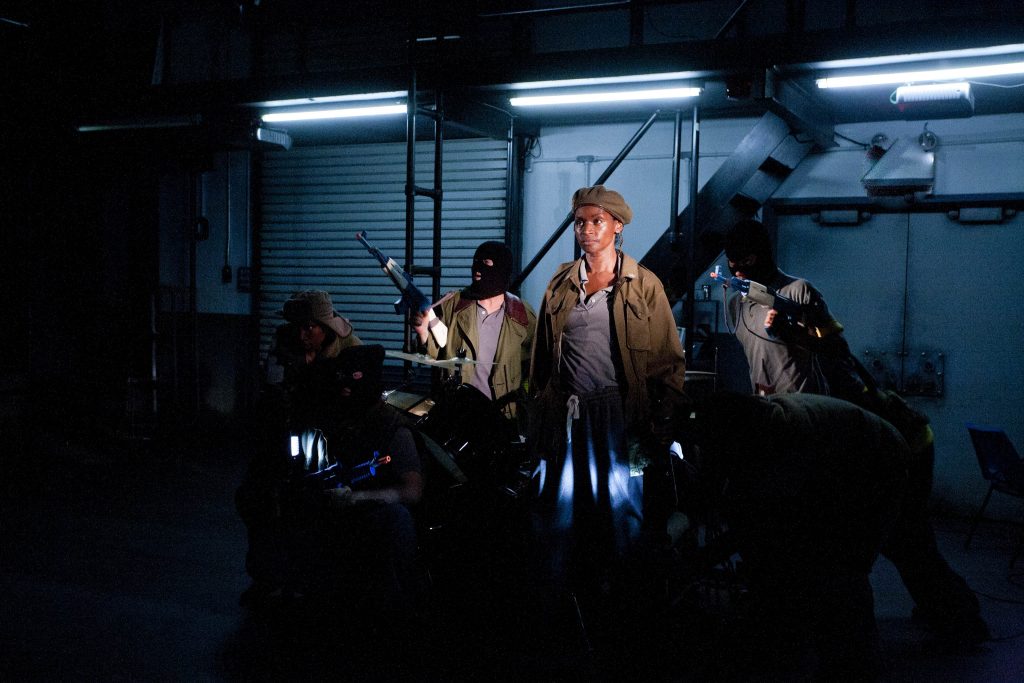

Jenny Jules as Cassius and ensemble in Julius Caesar at St Anns Warehouse.

Photo credit: Pavel Antonov.

“Do you want another of my real bugbears? Remember that when you see eighteenth or nineteenth-century etchings of actors performing Shakespeare they are in clothes of their own period. They’re not dressed in what a costume designer from their era might have fancied looked like a medieval outfit. Something has gone wrong in our approach. You’d have to ask the real theatre history geeks but at some point, from the turn of the century before last, a certain kind of director started thinking, ‘Oh! If I set this in the 1930s it’s really going to release the play.’ But all it does is put another layer of obfuscation between the audience and the text.”

The absence of tell-tale elements such as statistical placards (surely an obvious technique if they were to display figures for current prison populations, frequency of self-harm, and so forth) suggested to me that the trilogy isn’t really Brechtian. But there were many moments when the actors came away from their characters in the Shakespeare and were in their roles as prisoners, thereby creating two fictional worlds. I’m gently corrected. “No! It’s very Brechtian. You say you don’t see the placards but you hear the actors talking about their prison lives and you understand the prison hierarchy. It’s alienating, just as seeing the prison guards come on and stop the action is distancing. You wonder if the cast will be allowed to get to the end of the play. The aim is to create disturbance and tension that make you watch in a new different way.”

Reviewing the opening run of Julius Caesar, Michael Billington of the Guardian drew a comparison with Peter Weiss’s Brechtian 1963 piece Marat/Sade in which we see the inmates of an asylum act out the assassination of the radical pamphleteer Jean-Paul Marat. Crucially, the asylum staff frequently stamped their authority on the actors exactly in the manner that the warders at Lloyd’s fictional prison kept the performers in line. I recall particularly the moment when the actor playing Cinna the Poet was marched off to have her meds forcibly administered and actor Shiloh Coke began reading-in from the text as an understudy only to be attacked in a prison-related squabble.

Lloyd gives some precise context. “When I took Julius Caesar into HM Prison Holloway, I workshopped it with a group of prisoners and asked them whether the play spoke to them. I was thinking, ‘Here are a group of women, all on remand and absolutely terrified. Those who receive a custodial sentence will be shipped out to prisons miles away from their homes and families.’ After the first couple of weeks of looking at the play one of them said, ‘We’ve decided that this play is highly suitable to us.’ I think it was because their obsessions were the same as those of Brutus and Cassius: freedom and justice. So, by creating an institutional framework − a world of characters who are obsessed by the ideas of liberty and getting a fair shake, and who understand the currency of violence − you are helping the audience to believe that these women are capable of carrying out the acts that the plot requires of them.” Subsequently, Lloyd and other creatives at the Donmar Warehouse began working with Clean Break, a women’s theatre company based in north London who are known for strong political engagement and work in custodial settings. They assembled an ethnically diverse cast drawn partly from ex offenders. I interviewed the joint artistic directors of Clean Break for the Autumn 2020 issue of Plays International & Europe.

In 2005 Lloyd directed Schiller’s Mary Stuart (also at the Donmar) in a new translation by Peter Oswald who is a notable verse dramatist in his own right and a former playwright in residence at Shakespeare’s Globe and the Finborough Theatre in west London. Lloyd asked Oswald to streamline his text, and the final version was a mixture of verse and prose. Former Olivier Award winner Janet McTeer played Mary, and Harriet Walter was Elizabeth. A major (now topical) theme was how you can make unpopular decisions while retaining popularity with the people. The production transferred to the Apollo Theater in Manhattan with the same principal performers but adjustments to the male cast that several good judges saw as a strengthening. I asked Lloyd for an overview and her recollections of the Broadway transfer.

“It’s an extraordinary and timeless play and of course it isn’t really about Elizabeth and Mary Stuart at all really. The piece follows the lineaments of history but controversially puts them in a meeting that never happened. It’s about tyranny and freedom. Schiller is also saying that the only person who will ever really be free is the person who overcomes their fear of death which happens with Mary. Elizabeth is the one who remains eternally imprisoned by her fear of loss of power. It’s a fantastic piece of writing of which audiences will never tire.”

And what of the run in New York? “The new male actors were surprised at not being asked to do English accents. I was stripping non-essentials away; it’s not a heritage play and it’s about now. I loved working with the American company. American male actors are the very opposite of being neurotic! The culture of America allows actors to go on thinking of themselves as artists and students of their craft and continue to train in the way that a violinist will keep on practising until their death. American actors are unembarrassed to think of themselves as artists.”

I mention Deborah Warner’s controversial casting of her long-time collaborator Fiona Shaw as Richard II in a ground-breaking production at the National Theatre. It should be stressed that this was not a single-gender production and featured David Threlfall at the height of his generally stellar game as Bolingbroke. Warner said that the casting reflected her specific reading of the play. By contrast, Lloyd is I believe upfront in saying that her casting decisions are located within the politics of feminism.

“No, that could be misunderstood. I cast Julius Caesar for just the same reasons that Deborah cast Fiona as Richard II. Harriet played Brutus because she strongly identified with the character. I’m not going to name them, but there were several venerable British acting knights who came to see the play and confided in me that they thought Harriet was a much better Brutus than they had ever been. Those were humbling moments. But yes, I do have a feminist agenda in looking at who has access to our culture. I like to discuss who is allowed to use the crown jewels and what happens if you give the most powerless, voiceless people in our culture the prize pieces of our literature. Is it a car crash or do you hear something new when you listen to the text? It’s like listening to different instruments playing the same score. When you hear the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment play Monteverdi, it’s the same notes but you are hearing something different. Nonstandard casting usually means that the performers are not in any tradition such that they will worry about how their antecedents spoke the lines.”

Interviews with actors who have worked with Lloyd often describe how she has her own clear game plan but will always elicit opinion from performers and integrate their ideas when they are viable. I ask her to talk about that collaborative process. “I do come with strong ideas about what we’re not going to do. For example, we don’t waste any of our precious seven weeks’ rehearsal debating cuts. I have cut the text before we start. I’m not saying that we can’t replace bits or occasionally make further cuts but I’d rather spend six months with the text myself and be absolutely ready. In Julius Caesar, for instance, I had some strong ideas that Cinna the poet would be an understudy and would in some way end up being beaten or killed.

“Similarly, and perhaps crucially, I had the idea that Mark Antony would be able to manipulate the mob and use tools that we recognize from contemporary media to gain power. I was determined that it would not be a dozen actors all mumbling ‘Rhubarb’ and trying to look like 20,000 people. I would stylize it so that Mark Antony begins in my production with his life at stake. I remember after the slaughter of Colonel Gaddafi that sense of chaos and terror and murderous rampaging in the streets of Tripoli. Watching how people tried to ride that hysteria inspired my production. I didn’t want Mark Antony to come swanning onto the stage with ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen …’ He was there with twelve guns at his head when he began to speak. I wanted to look at how he’s going to get from this position to having control over them through rhetoric. I didn’t know how I was going to do it but it helps to have the best people in the world with you to make theatre. You know they are going to raise the bar and elevate any little ideas you might have to a sublime level. I’m willing to let go of anything I’ve brought into the room with me except the right of anyone to have an idea. And I’m prepared to listen to anything and try anything for the whole group to flourish because unless it catches fire with the group it won’t be worth doing.”

Suggesting that Lloyd either factors in Covid-19 or takes the broadest possible view and ignores the pandemic, I ask her if she is optimistic about the prospects for British, European, and American theatre. “I’m frightened that it will be hard to sustain the gathering of large groups of people in small spaces if there are alternative viruses forthcoming, and epidemiologists are saying that Covid is just one of many things that will emerge if we continue to keep animals in the conditions that we’re subjecting them to now. So, I’m nervous about that. And I’m frightened for commercial theatre because I don’t see how you can pay the wages on a big commercial show if you have to social distance in the audience. Theatre will survive this. There will always be theatre. It’s just a question of what kind of work we do and whether subsidized theatre has to reimagine itself and reinvent the transaction between itself and the audience. I feel theatres should now be like churches used to be. They should be in use daily by the community and be more like village halls.”

As somebody who takes their tin ear to a great deal of opera and sits in the gods as a member of the public, I’m intrigued to know how theatre directors make the transition to directing opera. It’s common practice. Rupert Goold, my interviewee in the Summer 2020 issue of Plays International & Europe, combines the two as does the director Melly Still. Katie Mitchell also seems to juggle work across both forms in equal measure. In contrast with Goold who says that opera singers are more akin to athletes than actors, Lloyd sees no great disparity. “It doesn’t differ; it’s just much more expensive to be on stage especially when the orchestra is in the pit. If you’ve got the chorus with you it’s hard to do what you do in theatre. Where an actor might suggest that you try another run-through of something or work on a specific aspect for an extra hour, you’re always aware in opera that time is expensive. And you have to collaborate closely with the conductor at all times.

“But if you’re well prepared and your patrons have hired you because of the way you work rather than expecting you to work in the style of somebody else, you can then create optimum conditions. When I had a company at English National Opera for the Ring Cycle we worked very much as we would, had we been actors. We talked about text, we worked without music, we worked in the evenings − all things that opera singers might have found nerve-wracking. But those great companies, especially the ones singing in English like English National Opera and Opera North, will adapt. I’ve done less opera in the last ten years and a reason might be that I don’t know how to bring the diversity and disturbance that I always look for to bear on opera. It concerns me that the audience lacks youth and diversity. You’ve got to get the product right to speak to a younger generation. It’s a huge issue. I’ve had some of my most fulfilling artistic experiences in opera, particularly at Opera North and especially with Benjamin Britten. But I’ve become anxious about the next generation of theatre and opera-goers and how to bring them in.”

I ask Lloyd about the arts-focused boarding school she went to near Malvern where pupils lived and breathed theatre. The students wrote, directed, and produced plays and performed them at outdoor festivals. “Lawnside School in Malvern! It had been founded by Isabel Greenslade, a friend of Bernard Shaw and Edward Elgar who – not in my day I hasten to add – used to play duets on our school piano which we all touched with reverence to try and feel the vibe. It was really art before everything else − drama and ballroom dancing before mathematics to the detriment I’m sure of all of us at many levels. We did Isadora Duncan-inspired Greek dancing − charging around the lawn with laurel leaves in our bra straps!”

Asked in her teens to assist somebody as a director, Lloyd had spent only an hour on the other side of the footlights when she resolved to strive to be a director rather than an actor. I ask her if she had become an actor, or indeed an opera singer, what role she would most like to have played. Laughing unrestrainedly and slightly shocked by the question, she pauses. “It would have to be Hamlet.” I follow up by asking if she would have done it in an androgynous style complete with the Chairman Mao suit and David Bowie hair that Maxine Peake adopted at Manchester’s Royal Exchange. “I think I might have done it as somebody whose family had clear ideas about how their child was to be defined in terms of gender, and the story would be about a breaking away from that to becoming their true self. I wouldn’t have done it either as a man or a woman − I’d have done it as a journey from one to the other or a journey to self. Luckily for the world, it’s not going to happen!”

We have touched on Chekhov throughout the interview despite Lloyd never having directed him. I ask her if she saw Toby Jones in Uncle Vanya at the Harold Pinter Theatre. She missed it and recalls directing Jones in a production of Pericles at the National. His Uncle Vanya has been recorded by Sonia Friedman Productions and Angelica Films in a style that she might enjoy.

Chekhov prompts Lloyd to recall an extraordinary trip early in her career. “In my twenties I received funding via the John Fernald Award to go to Russia and Soviet Georgia to watch directors at work in rehearsal. I went with Dominic Dromgoole who would become artistic director at Shakespeare’s Globe. We met at Heathrow Airport and embarked on this insane kind of blind date into the unknown with no preparation for Moscow in 1989, let alone Soviet Georgia where we heard gunshots outside the hotel and bombs going off. They were bringing down the statues of the Soviet monoliths. The memorable experience in Moscow was watching the great directors scurrying between university lecture halls and rehearsal rooms during long days in which they taught for hours. We met directors in Soviet Georgia who had taken a whole year of their students and made theatre companies out of them. Mikhail Tumanishvili had taken a class of students from fifteen years earlier, and they had been on stage or in the rehearsal room ever since. I’ve never seen work like it in terms of depth and detail.

“One experience was extraordinary. I sat in on a director’s class at the Moscow Art Theatre School with a female director. She was teaching in Russian but kept breaking off to speak to us in English. She had four students with her and told us: ‘These young people will never understand Chekhov like you British understand it. They simply won’t.’ She was calling bull on all the pretentious myths along the lines of: ‘You won’t appreciate Chekhov until you see it in Moscow!’ I said, ‘Why is that, why do you think this?’ She said, ‘I’ve been to Chatsworth. The Duchess of Devonshire has had to open a tea shop! That’s Chekhov!’ She thought Brits would understand it because we were seeing the unraveling of the British aristocracy and their fiefdoms in front of our eyes. A revolution was coming to sweep away that whole world.”

Brechtian elements include interruptions from guards. Harriet Walter and Sophie Stanton in The Tempest. Photo credit: Teddy Wolff.

I have what I believe to be one moderately hardball question but soon realize it will be batted away. Lloyd is insistent that there are few roles in Shakespeare (or indeed drama in general) for mature women or women who don’t conform to stereotypical appearance, physique, and accent. I cite Paulina in The Winter’s Tale, the nurse in Romeo and Juliet, Gertrude in Hamlet, Volumnia in Coriolanus, Tamora in Titus Andronicus, and the Countess of Roussillon in All’s Well That Ends Well. I tell her that the paucity of mature female roles is often exaggerated. But Lloyd invites me to do some Internet research which soon reveals that female characters have less than half the number of lines spoken by male characters. Even Rosalind, who pretty much controls As You Like It, speaks only 721 lines. Janet Suzman, who discussed the underrepresentation of women in her book Not Hamlet: Meditations on the Frail Position of Women in Drama, has noted that female characters have no soliloquies of significance. There is irony in the fact that two of the most coveted female roles in Shakespeare, Rosalind and Viola, disguise themselves as men within a few minutes of curtain-up.

I ask Lloyd what keeps her awake at night and when and where she was most happy. “If I stay awake it’s worrying that I’m not doing enough. As for happiness, it renews for me on a biweekly basis. I don’t have nostalgia for a then and there, but I’m easily delighted by simple pleasures. Of course, I would not be so happy if I were not so sad. I think Virginia Woolf expressed that idea much more eloquently than me.”

This is a director who has depicted a Roman assassination attempt through suffocation with a Krispy Kreme doughnut. She has put Wagner’s Siegfried in an Arsenal soccer shirt and compared Valhalla to the Gaza Strip. If I could suggest something to her it would be an all-female Much Ado About Nothing with the verbal dogfights between Beatrice and Benedick resembling the incendiary exchanges between her Kate and Petruchio in Central Park, with every line exploiting the sexual puns to perfection. There has already been a single-gender Much Ado at Shakespeare’s Globe starring Josie Lawrence and Yolanda Vasquez which was outstanding but by no means definitive.

Whatever her ideas for future projects, I doubt if Phyllida Lloyd ever stays awake at night worrying that they will be boring. At the moment, she is restricted to mentoring and encouraging performers ranging from opera singers to stand-up comedians over Zoom from her kitchen. When society unlocks, I can’t wait to see her next project. I bet the ranch that it will not be dull.