“Waiting for Godot” – Theatre Nation

Simon Jenner in Brighton

15 June 2022

“Where nothing happens. Twice.” Thus Vivian Mercier at this work’s Irish premiere in 1956. Blink and you’ll miss one of the most ambitious small-scale productions of nothing The Old Market’s mounted recently. It’s by David Glass and Theatre Nation; which after a tour from Tunbridge Wells and Hastings is on. Just twice.

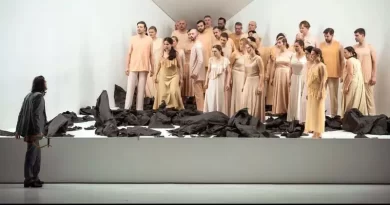

Patrick Kealey as Estragon.

Photo credit: Peter Mould – Stagesnaps.com

Beckett’s 1953 Waiting for Godot is both a play subject to the fierce proscriptions of first Beckett then his estate; and the directorial ambitions of those who writhe in his straitjacket. One otherwise faithful production was personally fiated in the 1980s for proposing an all-women cast. But that’d be telling.

David Glass doesn’t go that far, but his production aches with storytelling, where something will happen many times. And that sets up rhythmic wrinkles and overthinking which can drain the very joy and vaudeville Glass suggests he’s aiming for.

Vaudeville’s rightly been a dominant motif in Godot, particularly after the 2009 Haymarket production featuring Ian McKellen, Patrick Stewart, Simon Callow and Ronald Pickup.

A way in? Two Irish tramps in a French backdrop suggest – with beatings and offstage violence – those little ‘boy-scout errands’ Beckett self-deprecatingly admitted he ran in the war; for which he was awarded a Légion d’Honneur. Some errand.

There are great things here, so don’t hesitate even if you know the play, because you’ll go away re-thinking it. If you want convincing, read on.

Glass’s artistry is everywhere apparent, as designer and lighter too. ‘A country road. A tree. Evening’ is what we get, with a large stone-painted stage-cloth, and a clever Brechtian use of the stage where Jack Norris (Boy) stands ASM on the book when a character comically calls ‘line’ – blatantly not needed – to impose artificiality. You’d think it Brecht’s Baal, whose character throws a cane at the moon at play’s end, scuttering it down.

There’s a normally pinkish backdrop, eternal twilight, switching to lunar caustic blue with a full moon; or sudden dark. Unusually, Glass uses it to evoke a memory Vladimir invokes, making the sky go black then back. I’ve never seen a sky underscore mood so obediently.

For those who’ve seen Godot, you might think you were in one of those mid-noughties lead-swap productions like the NT’s 2014 Frankenstein, RSC’s 2016 Doctor Faust or the Donmar’s 2016 Maria Stuart. Vladimir’s the thinker, remembers as others don’t. He’s rational, even forceful, supports Estragon’s nightmares: “Who am I to tell my private nightmares to if I can’t tell them to you Didi?” Estragon’s the one with emotional memory, the melancholic whose way in is through images. “Leaves” he insists on his simile later on. “Like leaves.”

So Billy Clarke’s Vladimir (Didi) and Patrick Kealey’s Estragon (Gogo) seem the wrong way round. Kealey, also producer, might have chosen Estragon, but his great clarity, his directive speaking and intellectual detail at the end of his lines cry out for a level-headed Vladimir, the one who remembers what they did yesterday, can pick up Lucky’s hat (more on Lucky in a mo).

Clarke’s Vladimir is more emotive, shrouds speaking in an accent borne of many beatings, or so it seems. That’s more Estragon, more hesitation, indeed terror; and he doesn’t entirely help himself by speaking upstage on a couple of occasions, mercifully brief. He’s vocally expressive if not ideally clear, with a finicky, fiddling shyness that’s endearing; is more of an Estragon than Vladimir. Clarke like Kealey has real presence; you know you’re watching two terrific actors, a bit skewed.

Billy Clarke as Vladimir.

Photo credit: Peter Mould – Stagesnaps.com

We’re luckier elsewhere. Henry Maynard’s Pozzo is the booming landowner par excellence expropriating wherever he goes, a bully out of the Bullingdon smirching his authority, at least in the first act, and shreds some with distress in the second, even when occasionally he seems to forget he’s blind (the text allows that, Vladimir questioning whether he is).

Pozzo – whose brazen mix of contempt and pseudo-courtliness Maynard catches – jerks shreds of lèse-majesté perfectly too, when having tossed his chicken bones aside, he loans permission for the friends to scrabble and eat them: only if Lucky doesn’t claim them. ‘They’re yours’ Maynard says, more sotte voce than his usual, suggesting it’s grudging. Varies the carrot Vladimir offers Estragon.

Maynard centres his authority onstage. Glass has pushed his and the others’ physical cruelties to extremes not exactly sanctioned but in the right spirit, given where we are. This underscores our times even more than 1953, when capitalist terror poises naked: to exile refugees and undesirable tramps, sanction beatings, even murder. Beckett’s wartime refractions open livid in the way Pozzo berates Lucky. His ‘Up, pig!’ has more ferocity here; the two friends revenge-kick Lucky too; cruelty’s catching.

Occasionally you wish for modulation, more pathos, particularly in the second act, which Pozzo has to give as a bare ruined choir where once Lucky sweetly sang; that’s not what Glass aims for.

Pozzo’s to Estragon as Lucky is to Vladimir. This zen-like servant has no expectations, waits on orders, has no external free-will but lives in his head. The great moment of the play comes as when Pozzo declares he can think ‘so prettily’ if you jam his hat on him. Not long after Francois Testory’s Lucky begins, the others desperately stop him, rendering him dumb in his second-act appearance. By then only Vladimir remembers that Lucky ever spoke.

Testory’s supreme and this is why you should see this production. Lucky is always a virtuoso part or the play falls. Testory’s brilliance directed by Glass is to start allegro moderato and get to presto in a frantic warm-up I’ve not seen. His handling of words as he briskly circles his own tethered soul, feudally owned, is mesmerizing.

He also makes sense of the great Dublin philosopher Bishop Berkeley’s non-sense – diverting to Aristotle/Hume, stepping in the same thing twice. Berkeley asks: ‘Is it there if we don’t see it? Ah but God, (Godot) sees it all.’ It’s a fantastic riff on Becket’s learning: who plays with it dead-serious by dramatizing with laughter. Beckett pierces real intent with an Absurdist song. And Testory vocalizes this in an arc of ecstasy plummeted by violence. Later, he wails, a bit loudly, obscuring a speech because whatever Testory’s Lucky utters, even keening, you listen.

Glass overtly references French Absurdism too when tackling the Boy role – who comes on at each act’s end. It’s ingenious, Absurdism started before Godot (with Ionesco in 1950) and with Artaud’s friend Roger Vitrac’s surrealism in 1928. Of course Beckett snorted it all in the air. But.

For Jack Norris’s Boy, Glass imports overt Absurdism in the spirit of Vitrac whose Death featured a laughing farceur featuring a giant nine-year-old girl in his 1928 Victor, or Power to the Children. So here Boy’s wheeled on in a giant screen made-up in black and white, dropping a mask from Boy to a cackling malign Godot himself. Theatre of cruelty or what? Theatre of leer?

It’s brilliant, all yellow, white and red (all credit to film-makers Sam Sharples and Adam Clements too, a superb spectacle), owns a wild permission from 1928 as well as the 1950s; but wrong. Boy’s an innocent go-between, explicitly runs off frightened at the end. Not here. If Godot was meant to wheel on stage, to paraphrase Beckett quoted in the programme note, he’d have written him in. It’s great Artaud/Vitrac, but again robs Beckett of pathos. Norris, making his debut is excellent to his brief. 23, he’ll soon jump out of his screen.

There’s touches where Clarke and Kealey inhale that terror and pathos that renders Godot heart-breaking and hilarious by turns. Kealey’s ‘leaves’ manages it sometimes too. Clarke in any case is more attuned to tenderness. It’s just that they can never give it to each other; those almost tearing-up moments never, like Godot, come.

The nearest we get is when Pozzo of all people announces: “They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.” Its devastating, riffing off St Paul’s mere misogynistic take. Vladimir reprises it briefly. We need more of this orphaned melancholy. And I miss it.

There’s literally fantastic movement direction too, as when in Act Two the friends debate whether to help the now blind Pozzo up, and take the eternity they have. All prone on the floor as if in some vertical Comedy About a Bank Robbery scene that’s collapsed, it’s memorable, existential even.

You’ll be lucky to see another Godot at the moment. With caveats aside, those two leading roles reversed, and Vitrac’s hi-jacking Norris’s otherwise promising Boy, this has real virtues: a solidly unpleasant Pozzo in Maynard, full of presence, and an electrifying Lucky in Testory.

Glass has put everything into this production, and if you’re coming to it for a first time, your joy should be unalloyed. There’s a need though for the sky to keep quiet and wax natural, and that’s cue for the rhythms and ultimately truth of a production.

No director or actor wants to be Lucky to Beckett. Trust your luck to Beckett though, just a bit more. His humanity shines through even this production’s cleverness, though someone’s chucked a stick at the moon and tenderness crashes down. Testory’s Lucky though, doesn’t notice. And somehow blesses all of us.