“The Nature of Forgetting” Théâtre des Capucins

Dana Rufolo in Luxembourg

17 January 2023

Tom doesn’t mind the gaps in his memory; The Nature of Forgetting, a touring UK production by Theatre Re of London that played at the Théâtre des Capucins in Luxembourg city from 13 to 15 January, shows how 55-year-old Tom, who has Alzheimer’s, navigates the still waters of memory loss.

Photo credit: National Taichung Theatre.

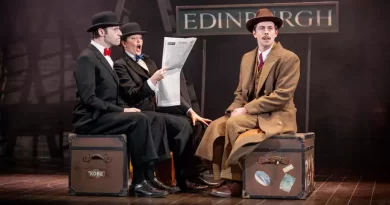

The Nature of Forgetting is a scientifically-vetted dramatic rendering of reality seen from the perspective of Tom (Guillaume Pigé). Almost totally independent of language, it is physical theatre using three other actors (Louise Wilcox, Eygló Belafonte, Calum Littler) as Tom’s friends and family, and Tom himself, to re-create sounds and physical movements associated with memories that slither around in Tom’s mind. Surrounded by a soundscape as pleasingly atonal as Arnold Schoenberg’s (composed by Alex Judd), caught up in swirling speedy movements that treat the stage floor like ice and the actors like ice skaters, we the audience are thrown into Tom’s happy state of existence – a “good trip” kind of place. One can only hope that the pleasant insulated cocoon Tom inhabits – suspended as it is somewhere beyond the endless succession of days and nights and clock-regulated events that mean feet-on-the-ground existence for the rest of us – does indeed accurately reflect the agreeable state of consciousness of an Alzheimer’s patient.

Neuroscientist Kate Jeffery says she “explained the concepts of the neurobiology of memory” to the company when the piece was devised by Pigé and its members, so what we see on stage gets as close to truth as possible. There is no paranoia, no terror, in Tom’s world. No fear of dying also. But unfortunately, in the final mind’s eye view of the matter, The Nature of Forgetting falls into the category so aptly called “dementia fiction” by bloggers from Queens University, Belfast. For when all is said and done, like locked-in syndrome, Alzheimer’s is yet another “undiscovere’d country, from whose bourn no traveller returns”.

Two racks of clothing, mostly jackets, and four school desks, their corresponding chairs, and extremely long wooden ‘pencils’ are the major stage props that keep the characters’ jivy movements hands-on. Tom can’t absorb the instructions a daughter gives him concerning which jacket to wear, and he puts on one that he used to wear in secondary school. His mind whirls back to that era; in fact, his memories seem focused on those years of growing up. One of the girl characters is his girlfriend and eventually becomes his wife.

Photo credit: National Taichung Theatre.

There is, as I said, various kinds of music or sound, generated by an onstage instrumentalist and a percussionist; some is quite pretty: jingle bell sounds like fairy lights blinking on and off, and some is jarring and loud but doesn’t grate on one’s nerves. Every so often, everything grinds to a halt. All the characters freeze. And then the frenetic activity re-commences … over and over again for 75 minutes. Desks get moved, regrouped, put off stage, brought back on stage, and the characters run around and almost but not quite into one another; they approach but never stop long enough to chat. Tom’s “significant others” have lost the habit of speech.

Other items of clothing from the racks bring back other memories – his mother’s scarf, for instance, pushes Tom to ‘visualize’ jumbled-up fragments of memory about his mom sending him off to school, sometimes by bike. It is, in fact, the racks that provide the most symbolic and consequently dramatic act of the entire show. At the close, the characters slip the hanging garments off the clothes hangers and toss them up into the air; the final image is of rows of wooden clothes hangers naked on their racks: no more memories; the end. It is a simple but startling dramatic metaphor.

Florian Zeller’s play The Father describes the growing disorientation of a character who still communicates with the outside world, albeit by using language as an expression of paranoia, anxiety, and fear. Zeller’s play is profoundly more dramatic in that the main character is positioned inside a geographical place, a social community, a relatively kind family even if he is in conflict with his surroundings. The Nature of Forgetting is more a performance piece than a drama – a living laboratory where the most modern suppositions of “what is left when memory is gone” are given physical form on stage. Both theatrical works are needed to help us understand what might happen to us or to loved ones in this era when nobody is sure to exit life unscathed by some form of senility. We need to think ahead of time to prepare ourselves for tolerance and empathy. By creating full-bodied examples of possible scenarios before our eyes, theatre has always been the best of teachers.