Sir Michael Boyd interview

September 2023

[Jeremy Malies interviewed Sir Michael Boyd in 2012 for the print version of this magazine shortly after Sir Michael had stepped down from the Royal Shakespeare Company. Sir Michael died in August 2023. This interview is left exactly as it appeared 11 years ago.]

Sir Michael Boyd is the outgoing artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company. He looks back at a hugely successful ten-year tenure that has included the audacious Complete Works Festival, his own critically-acclaimed Histories Cycle, the end of a painful period at the Barbican and rewarding London seasons at the Roundhouse in Camden.

He reflects on international collaborations, indulges in some dream interpretation theory, compares Shakespeare with The West Wing and advises every Shakespeare director to start by thinking about Mary Queen of Scots. Sir Michael explains how one chance glimpse of a Georgian director across a packed theatre proved more gratifying than a string of industry awards.

Your production of Pushkin’s “Boris Godunov” is currently in the RSC’s Swan Theatre. It was always going to be topical in terms of parallels with Russian politics and has become even more relevant during the run of the show as a result of current events in Egypt. Talk about its message for today.

There were three layers of the play that interested me. One was Pushkin’s love affair with Shakespeare and the period the play is set in, i.e. our Renaissance and their period of troubles under Boris. Another layer was the time of Pushkin under the censorship of Tsar Nicholas. After a period of liberalisation under Alexander, there has been a crackdown under Nicholas. Pushkin was interested in a portrait of creeping tyranny from unlikely sources. There was hope that Nicholas would prove to be a liberal like Alexander and, increasingly, Nicholas found it necessary to take the reins into his own hands and rule with an iron fist – in the favourite phrase of Pushkin “silnaya ruka”.

I was also interested in the time of Russia now where, again from the unlikeliest source, comes just the same kind of tyranny. You spend most of the play hoping that the pretender, Dmitri, will prove to be a breath of liberalising air but Dmitri quickly becomes the slave of his own trajectory. He ends up gaining power with a tyrannous, murderous act in exactly the same way as Boris Godunov had.

Boris Godunov. Photo credit: Ellie Kurttz.

There were those who hoped that after the death of Stalin, the liberalisation of Khrushchev would lead to an open society. But that collapsed under Brezhnev and then, with Gorbachev, they were hoping for another opening of Russian society and that seemed to be coming true under Yeltsin. On Yeltsin’s collapse, Putin arrived talking of change, welcoming foreign influence and promising democracy. He has moved further and further away from it, to the point where he’s increasingly visible as a new kind of tsar, effectively reappointing himself as president beyond the constitutional limits.

The RSC’s 2013 season opens in January with “The Winter’s Tale”. It’s a tough piece to do with a 16-year gap between the two parts after which a teenage girl calls the shots. Talk if you will about the way in which many of the plays in the new programme deal with the empowerment of women.

The last time we did The Winter’s Tale I asked David Farr, who is a confident, bold and interpretative director, to tackle it. He’s not scared to be authorial. Similarly, Lucy Bailey [Julius Caesar for the RSC in 2009 and founder of the Print Room venue in west London] is muscular in her approach. She will have a particular take on the fate of Perdita and Hermione.

There are many of my heroines in the shape of directors and writers throughout the programme. Emma Rice is also directing in the Swan Theatre. She’s doing The Empress, a play by Tanika Gupta (another heroine of mine) about Queen Victoria who is not necessarily a heroine of mine!

I love the fact that Maria Aberg is directing Pippa Nixon as Rosalind in As You Like It, having first made her mark at the RSC with the Roy Williams play Days of Significance which was commissioned to be a spin-off from the Much Ado About Nothing in the Complete Works Festival of 2006-7. Maria was directing this new Roy Williams play and Pippa was playing the Beatrice figure with a ferocious command of both the wit and the filthy language that Roy put in her mouth. Now Pippa is coming back to play the more sophisticated, more beautiful and more challenging heroine, Rosalind, who is almost a female Hamlet to my mind.

It was your innovation to embrace the ensemble ethos once more and set up two groups on long-term contracts. How did you introduce this idea and go about recruiting the ensembles?

The RSC was founded on ensemble principles, inspired at least in part by the great European ensembles of the Fifties and Sixties. I didn’t believe the agents’ hype that it was important for young actors to go straight from college into a fashionable drama series on TV or wait around for film jobs. The actors I knew wanted to stretch themselves, wanted to learn and had the humility to learn. And they did learn – most of it off each other. I believed there were enough of our best actors who would make that commitment. Rather than seeing life as too short to spend 18 months or three years with the RSC, I felt they would see life as too short not to have done something as ambitious as that at least once in their lifetime.

“The Empress” opens the season in the Swan Theatre. It’s got issues of race, class and even instability of the monarchy. It’s likely to consolidate the RSC’s reputation for new writing. Tell me more about the play.

The thing that strikes me most is how ignorant I had been, before reading the play, of the depth and richness of Indian presence in Britain in the nineteenth century. I had little understanding of the role of London in the birth of the independence movement in India. I had no idea of the specific injustice and cruelty of the fate of so many Indian nannies who had been looking after children in English families before coming over and being deserted on the quay at Southampton because it was not socially acceptable to have a black governess in this country. At the centre of the play is a young girl who is duped but embarks on a journey towards dignity after an enormous smack to her self-esteem.

The 2013 programme includes “Titus Andronicus” directed by Michael Fentiman. Will it be as gory as Lucy Bailey’s version for the Globe when a mobile field hospital dealt with the dozen or so fainting cases every night? Is it likely that Lucy – who will be on hand as she directs “The Winter’s Tale” –will pop in and suggest a bit more mutilation and projectile vomiting?

Titus Andronicus cuts to a lot of our nightmares about our body and violence that can be done to the body. In the relatively enclosed space of the Swan, we had our own incidents of fainting during a battle scene in our English history cycle. Michael will do it his own way and Lucy will not impose her own particular notions of sadism on him I’m sure!

There is much interest in Thomas Middleton’s “A Mad World My Masters” directed by Sean Foley. What can we expect?

It’s one of the projects that excites me most because I’ve seen it in development. Sean is an artist whose work I’ve admired enormously. He was in a workshop production of Measure for Measure that we did in our studio. He played Pompey and I realised how much he invested in Shakespeare and how hungry he was for theatre of that period. He came back and said he wanted to look at A Mad World My Masters. He did it as a studio workshop – a laboratory production. It was a beautiful, hilarious take which he set in Fifties Soho using the techniques from his previous Right Size company. At the same time it made perfect sense of a very difficult Jacobean text. I immediately commissioned him to do a full production.

What are the likely building developments at the RSC? What will happen in The Courtyard/The Other Place area?

We’ve recently been given planning permission to pursue our preferred option. Rather than having to knock down what was The Courtyard, we will convert it into a complete rehearsal complex. Our rehearsal rooms are currently 15 minutes’ walk from the theatre which is not ideal. Most importantly, the planning permission covers a new “Other Place” which will flexibly seat between 150 and nearly 300. There will be a new costume shop and store. These can now be brought into the town, when to date they have been at a warehouse in the suburbs of Stratford. The costume store will be open to the public and should provide an enjoyable experience for people who want to look around.

You took over from Adrian Noble as Artistic Director of the RSC in 2003 with the announcement coming in 2002. Few would argue that it was a low point for the company. You soon turned things around and in April 2006 you began a year-long Complete Works Festival. It included “Titus Andronicus” in Japanese, “Richard II” in German and “Measure for Measure” directed by Sir Peter Hall. You directed “Henry VI” yourself. What made you undertake such a project?

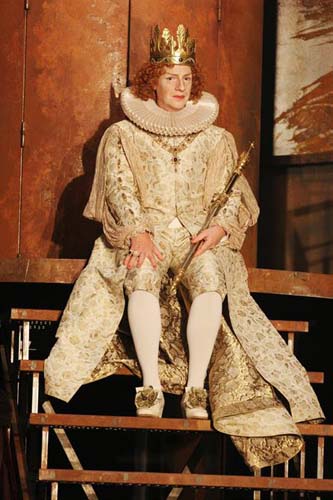

Henry VI. Photo credit: Ellie Kurttz.

I consider myself fortunate to have taken over the RSC at a low ebb but not merely for the superficial reason that you would be bound to get a few things right and people would say: “Fantastic!” There was the deeper reason that only when an organisation as important as the RSC was at a low ebb would somebody like me be allowed to be as radical as I was. If a body like the RSC is doing well, the danger is that it can behave in a very conservative manner. So my pitch for the job when I was interviewed was quite radical and idealistic and I was given that mandate. I stuck to it and the Complete Works was one manifestation.

But that was very much a ‘back to the future’ thing, inspired by the courage and insight of Peter Daubeny’s World Theatre seasons [1964-1973] at the Aldwych. The tales from these were inspiring and I know how those seasons must have informed the RSC’s work at the time and made it more ambitious. If you’re commissioning Ingmar Bergman to come and work with you it’s going to up your game!

I wanted the same to happen with us and certainly had that experience during the Complete Works festival. I was four weeks away from going into rehearsal on Richard II when I saw the Berliner Ensemble’s absolutely wonderful version in The Courtyard and I thought: “How will I ever top that?” which is a great emotion. That’s what you’re looking for. You want to be inspired to do better and the festival did that through Greg Doran’s Anthony and Cleopatra with Patrick Stewart and Harriet Walter, Josie Rourke’s King John [Richard McCabe in the title role], Marianne Elliott’s Much Ado About Nothing with Tamsin Greig, the first half of our history cycle which I directed, Ian McKellen’s King Lear [directed by Sir Trevor Nunn] and Rupert Goold’s first major Shakespeare production – his Arctic version of The Tempest [also starring Patrick Stewart]. We didn’t come off badly by comparison even with the Ninagawa Company and the Berliner Ensemble!

Richard II. Photo credit: Ellie Kurttz.

You took over soon after the RSC left the Barbican. It must have been a difficult time.

I understood the momentum towards moving out of the Barbican. I don’t think the RSC had managed its role in the purpose-built Barbican very well. It was not a happy place to work; the relationships with the production teams and the unions were not happy – not grown-up to be frank. The relationship with Guildhall School of Music & Drama – that was a wonderful opportunity to have what I would call an academic theatre in the middle of London with a working international theatre company and a first-rate drama school hand-in-hand. I think the decision to breeze-block up the doors between the Barbican theatre, the RSC and the Guildhall was the worst mistake ever made.

The return to London in the form of seasons at the Roundhouse in Camden where the main RSC stage can be replicated must have been a highlight of your tenure. Can you talk about the Roundhouse as a venue?

The relationship with the Roundhouse began in May 2008 with the History Cycle though not then with a view to a formal arrangement and doing it regularly. We enjoyed it so much and had such a good understanding with Marcus Davey and his colleagues. It was there that I did reach a moment of thinking: “I’ve finished the histories.” The last performance of the last cycle was Richard III. The audience included Robert Sturua [Georgian theatre director b.1938]. I had seen his production of Richard III when I had been a trainee at Coventry and taken the train down to Euston and gone to the Roundhouse and been blown away by Ramaz Chkhikvadze in the title role. And there was that man [Sturua] in that theatre watching that play. And his huge smile at the end of the show was better than any of the Oliver awards!

The Roundhouse.

You are on record as saying: “Our contemporary dramatists badly need to reread Shakespeare.” You will be too chivalrous to mention names but can you talk generally about how a need to reread Shakespeare manifests itself in contemporary writing?

That quote is quite old! Writers like David Greig and Lucy Prebble really do understand the joy of bold, inflective, heightened language and the inextricable relationship between individual fate and public life. There’s a generation growing up now who don’t see narrative as unnecessary.

I think the RSC has had an influence with the commissioning of authors to write plays after having looked at Shakespeare both at home and abroad. Russian writers did workshops in Moscow with us recently and produced pieces such as The Grain Store and The Drunks which we staged at The Courtyard in Stratford. Think of it. We premiered two Russian plays at a 1,000-seat theatre. Initiatives like that, the Royal Court’s many international workshops and even American TV have been important. Serials like The West Wing have woken writers up to how it’s possible to talk about power, mortality and love within a rattling good narrative that avoids the storytelling becoming abstracted and dry.

You described Shakespeare in a television interview as “appallingly contemporary.” You were prompted on that particular day to say this by what you were seeing of religious schisms in the Middle East. What did you mean in a more general sense?

I flatter myself to think that before I became aware of the wonderful work of the new historicist critics such as Stephen Greenblatt, Jonathan Bate and Jim Shapiro, whose writing very intelligently places Shakespeare’s work within the context of the English Reformation and all that it meant; even before that, as somebody born in Belfast and working on the west coast of Scotland, I was alert to the fact that Shakespeare’s writing was still immersed in England and in the conflicts with which I was all too familiar in my native Northern Ireland.

You were dealing with the consequences of changing the way a whole society thought within one generation. The way they thought, worshipped, celebrated, gathered and related to each other. Even when I was working on an earlier production of Macbeth with Iain Glen at the Tron Theatre, Glasgow, the first question I would ask was: “Where is Mary Queen of Scots? When approaching any Shakespeare play always ask: “Where is Mary Queen of Scots?” Where is the legitimate monarch who has just been executed by the reigning monarch? Mary Queen of Scots was in a way also partly Lady Macbeth. She was in both. Never make the mistake of thinking that the author is one person in a novel, a play, a poem. They are everywhere in the way that we are all the people in our dreams. We’re not one person. That baby crying in the corner is you as you dream it as well.

Macbeth 2011.

Photo credit: Ellie Kurttz.

I’ve always seen Shakespeare’s writing as a great deal more political than had been perceived to be the case in English productions up until recently. Another central experience for me was suddenly waking up at the tender age of 23 in Moscow, a society that had had its way of thinking changed overnight in the early twentieth century. I saw how the theatre worked under censorship and ideological conformity and I saw how political Shakespeare was for the Soviet theatre makers.

The RSC’s musical “Matilda” will open at the Shubert Theatre in Manhattan in the spring of 2013. Which aspects of the story do you think are most likely to enthuse American audiences – both children and adults?

It’s a story that will appeal to left and right. Americans will respond to the wit. New York audiences are the sharpest in the world in terms of crackling verbal wit. That’s where they live and that’s what they do so Dennis Kelly and Tim Minchin are the perfect writers for this. Audiences in the US respond tremendously well to an individual hero’s narrative journey.

Staying with America, the New York-based Wooster Group made a great impact when they collaborated with the RSC on Mark Ravenhill’s production of “Troilus and Cressida”. What has been your experience of working with them?

I’d read an enormous amount about the Wooster Group before my first exposure to them which was their take on The Three Sisters. I completely adored it. Not all my friends did – they felt they were watching Chekhov in bits on the floor! But I thought I was seeing the sap of Chekhov released from a carapace. Irina, around whom everybody focuses in terms of her marriageability and potential to escape because she’s so gorgeous and young, was played by a 70-year-old actress and it was so powerful. I love Elizabeth LeCompte’s playfulness, her lack of sentimentality.

In the end, although Troilus and Cressida was a project that had originally been conceived for Elizabeth and Rupert Goold, Mark Ravenhill turned out to be another very good partner for her in that as a writer, he was used to being authorial. They had a fantastic time doing it. At its best, with the ensemble showing not just the contrast between two different theatre cultures but the differences between the Greeks and the Trojans, the production was very effective.

Regardless of which projects you take up, have you set any general objectives for yourself over the next few years?

To try and work with intimidatingly good people who can both inspire and challenge my own practice.

What next?

I’m trying to be sensible about what I say “no” to and what I say “maybe” to. I’m working with two of the writers I most admire on projects. I’m doing exploratory work on two things with David Greig. And there’s something that Lee Hall [The Pitmen Painters from the book by William Feaver, screenplay and subsequently lyrics for Billy Elliot,] and I would like to do together. I’m also involved with Filter, a group of young theatre makers who I commissioned several times at the RSC. I’m working with them on a mad idea for a stage western. And there’s some ‘proper’ plays as well. I’m planning a production of The Cherry Orchard and there’s another Chekhov-related project.