“Romeo and Juliet” at the Almeida Theatre

Jeremy Malies in north London

16 June 2023

Rebecca Frecknall is too experienced and reflective to be tempted into a flamboyant choice for delineating the two families and the reason for their quarrel, which often sends this play into a concept production with little investigation of central themes. I couldn’t see any reason for the ancient grudge mentioned in the prologue which is given to us here as text projected onto what I took to be the Verona city walls. The entire cast pushes on a wall at the start only for it to pivot and become the floor which I suppose warns us that the show will be disorientating.

Not a second is wasted, there are no set pieces that might prove staid (the thumb-biting insults go), and even the masked ball sees Romeo (Toheeb Jimoh) donning no more than a handkerchief. Perhaps this was the one element that might have been more leisurely. Across extended sequences, Frecknall advances the plot with movement alone and there is much fluid (unmannered) balletic movement here which is hardly surprising since some of the music is by Prokofiev for his 1935 ballet about the lovers. Elements of physical theatre surrender to ballet and back again.

Frecknall must have worked with Isis Hainsworth (Juliet) to bring out all the textual hints that this is a self-possessed teenager who shows poise. She can be both ardent and skittish within a single line: “I have forgot why I did call thee back.” Hainsworth’s many high points include describing an abject fear of being surrounded by dead Capulets (including the recently slain Tybalt) as she realizes that she is being asked to sleep off an induced coma in the family tomb.

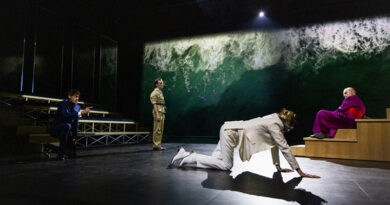

Isis Hainsworth and Toheeb Jimoh. Photo credit Marc Brenner.

Jimoh comes into his own when visiting the apothecary (Daniel Phung) and in his final exchanges with the friar (Paul Higgins). He is also personable and convincing when pondering his banishment from Verona.

Just for once there are no homosexual overtones between Romeo and either Mercutio (Jack Riddiford) or Tybalt (Jyuddah Jaymes). Riddiford starts well as a personable trippy Withnail and I character but fails with the signature Queen Mab speech. He tries to do it in two gears, but grinds to a halt in the second half and fails to convey the sexual innuendo.

As Friar Lawrence, Higgins bathes the theatre in his soft Lanarkshire vowels, suggesting a true empathy with the lovers. As Nurse, Jo McInnes goes so far beyond support that it’s almost a virtuoso performance as she banters with the younger generation while looking out for her charge like a mother bear. She has a light touch with broad humour and brings depth to what can often be a caricature of earthiness.

Isis Hainsworth and Toheeb Jimoh. Photo credit Marc Brenner.

When not involved, cast members sit around the edge of the stage with even the unlucky Tybalt and Mercutio being resurrected to watch the continuing carnage. The sexual or even tactile interaction between the lovers is not a focus here and certainly isn’t laboured. Never has Juliet’s chiding of Romeo “You kiss by the book” been more apt. Frecknall has a laser-like focus on how this community interacts, the dysfunctional parent–child relationships, and the view of Juliet as a commodity to be packaged up for Paris (an unexpectedly affable James Cooney).

I wonder how the curriculum audiences (it would be a great introduction for them) will digest a plot in which two youngsters die because a letter is misdirected when present-day teenagers would send texts. I hope young theatregoers note that it is the old who let the young down here.

Both the lovers seem experts on the qualities and peculiarities of light, constantly referencing the heavenly bodies. Lee Curran’s lighting design is stark (there are even LED strips on Juliet’s balcony) but he always taps into what the youngsters have been saying. No sepulchral gloom here in the Capulet crypt; several cast members light a hundred or more candles for the young woman who wanted to cut her husband’s spirit into little stars. Frecknall’s generally minimalist approach means that designer Chloe Lamford is reined in here for a scene that might have offered her real scope. There is no tomb to speak of and Juliet is simply placed on a pine trestle. Hainsworth excels when showing us that her vital signs are kicking in just as Jimoh (producing impressive quantities of spittle from the poison) is croaking his last.

There is no noticeable period and few props, with the fights (directed by Jonathan Holby) progressing from daggers to generic revolvers. Initially I was confused that the blocking made no sense, with characters commenting on things on stage that they could not possibly have seen. Finally, the penny dropped as if through treacle: Frecknall deliberately makes the blocking non-naturalistic if it suits her.

“Two hours’ traffic of our stage”? I don’t go to Shakespeare with a stopwatch but I soon know when I’m bored, and Juliet frequently speaks of time not flying fast enough for her. Frecknall’s commitment to keeping this uncluttered never flags. If you absolutely need the quarrel to be rooted in specifics, you will be disappointed at first but surely won round. This is fresh, avoids being formulaic, and is completely free of any kind of artifice. The whole creative team appear to have heeded advice from the friar: “… the sweetest honey / Is loathsome in his own deliciousness.”

.

.

~