“Pessoa – Since I’ve Been Me”, Robert Wilson

Dana Rufolo in Luxembourg

★★★★★

10 January 2026

Pessoa – Since I’ve Been Me is one of the last performance pieces Robert Wilson developed before he died in July 2025. In Luxembourg the performance was advertised as an homage to the visionary theatre-maker as much as Robert Wilson saw it as an homage to the Portuguese author Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935). It premiered on 2 May 2024 at the Teatro della Pergola in Florence and will be at the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris during June 2026.

Photo credit: Lucie Jansch.

Pessoa is considered one of the greatest Portuguese authors of the twentieth century. He wrote in different styles but did not use pseudonyms. Rather, he invented imaginary distinct human authors responsible for these different styles. He called these personas by the neologism: heteronyms. The writing of three of these heteronyms, Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis and Alberto Caeiro, and their books The Keeper of Flocks, Faust, and Book of Unrest were used in Pessoa. Darryl Pinckney, the author who has already collaborated dramaturgically on seven other plays by Wilson, is responsible for arranging the texts chosen.

The play began with a prologue. A man is sitting before the screen on stage. He is wearing a black suit and a tie and has prominent eyeglasses, thick eyebrows and a moustache He is totally expressionless and is making gestures that are impossible to decipher. We hear a melody, repeated endlessly. On the screen in front of the stage, we see images of reddish rising or setting suns; one has a Christian cross on it. A pencil-like cylinder is also projected, perhaps in keeping with the theme being Pessoa’s writings.

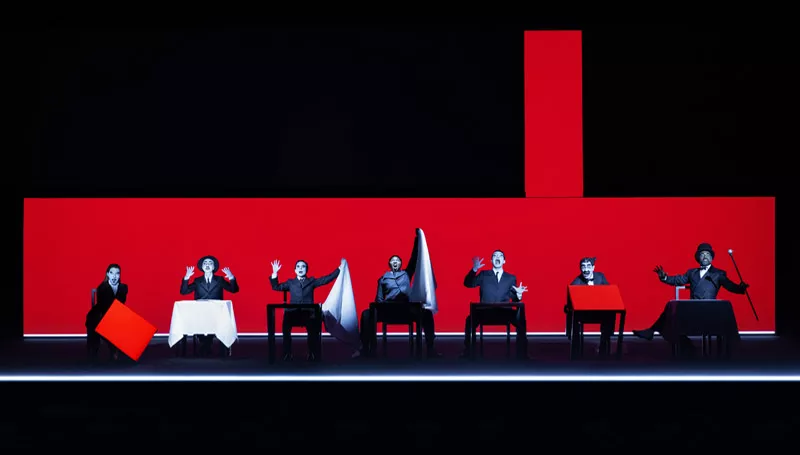

The sound of broken glass – a champagne flute being tossed to the ground, we eventually understand – is so loud and unexpected that my startled neighbour in the audience jerks involuntarily. This is the sign that the performance is beginning. The texts by Pessoa begin. We hear the mysterious and hopeful statement, “I know not what tomorrow will bring.” Our clownish man and six other clowning actors bounce into the limelight; they are in a merry party mood and we hear the sound of a smashed champagne flute after each cavorts around.

The tone becomes gradually melancholic during the 90 minutes. We see one actor reading a letter from Ophelia, and simultaneously to her amplified words reaching us, we see the outline of her hand reflected on the sheet of blank white paper as if the letter was composed of the shadow of her hand. A man in a room lifts a pen to slowly write. We hear, “I don’t feel myself linked to it in any way.” Then, “I am merely the place where things are thought or felt or said.” We hear that love letters are ridiculous, we see depersonalized figures. A link to mysticism develops. “I saw God in all the world’s substance … I will die and I will leave … a life, I long for death.” Repeated sounds, in a typical Wilsonian loop. Tinkling sounds, like a music box. Pessoa progresses inexorably from merriment to existential tristesse.

Photo credit: Lucie Jansch.

The lighting, stage setting and action of Pessoa is iconically Wilson’s. The play is composed of two components, one of sound (speech) and the other one visual (images). The sound ‘track’ includes speech – quotations directly from Pessoa’s writings which are spoken by the actors and yet amplified and broadcast by speakers as if the actors did not directly speak those words but instead as if they had been pre-recorded, which possibly they were – music and abrupt ear-shocking noise like those sounds of breaking glass – and to this ought to be added the audience’s subvocalizations when reading the quotations in the form of surtitles permitting audience members to understand texts from Pessoa that are spoken in Italian or Portuguese or French or English; translation was provided into English and/or French.

Colour projected in geometric patterns onto parts of black and white scenes via gels, rapid movement, slow movement and stillness comprise the visual track which is kept as linear as possible, as if one were watching an old reel from the era of the silent film. The impression was of two modalities presented as if they were sliding sensorial panels, gliding one over the other.

Keeping the sensorial elements presented on stage as distinct and separate as possible has always been a hallmark of Robert Wilson’s work, but in this late piece the visual and aural elements are rarely cohesive, making the experience as much the opposite of a Gesamtkunstwerk as possible. The effect is rather, as said above, of these elements appearing to slide along the horizontal length of the stage (the main stage at the Grand Théâtre is 20.20 meters broad), a sense of flatness prevailing. Even the actors when they enter nimbly to create comic numbers which are mimic in nature, as they did chiefly at the beginning of the piece, worked along the horizontal and avoided clustering in a way that would give the sensation of depth.

All in all, it was a visually stunning performance that suggests great meaning, even if it is difficult for audience members to ascertain just exactly what the profoundness, or meaning of this meaning, really is.