“Take me Out”: Helen Hayes Theatre

Glenda Frank on Broadway

17 April 2022

Take Me Out, a locker room dramedy by Richard Greenberg, now at the Helen Hayes Theatre, brings us a feast for eye and mind. The ensemble of gifted actors – who are knockouts in the all-together – explore the complexities of friendship, racism, homophobia and baseball.

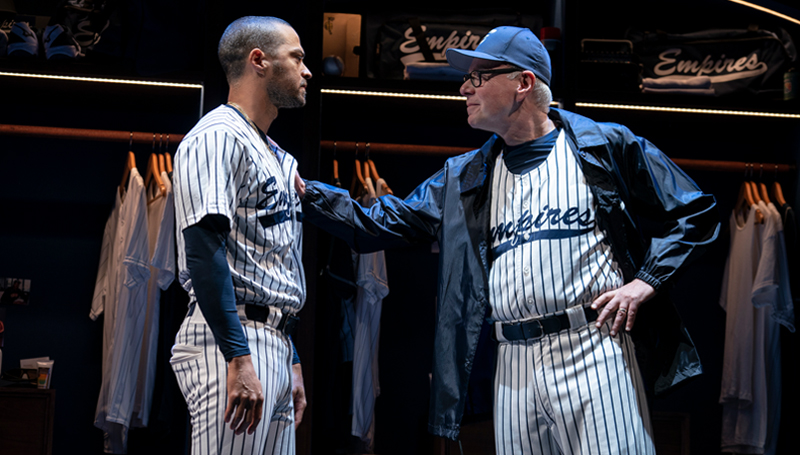

Jesse Tyler Ferguson and Jesse Williams. Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

(Phones are safe-boxed as audience members arrive – to protect the actors; they are restored after the play.) I miss Denis O’Hare, a comic superstar who played Lemming’s business manager in the 2003 premiere, but the revival is never lacking. It’s alive with quotable lines and smart humour. In 2003 it won several Tony and Drama Desk awards. The piece has aged but the human stories remain compelling, and playwright Richard Greenberg’s mixture of comedy and tragedy is heady stuff.

The story focuses on Darren Lemming (Jesse Williams), a mixed-ethnicity baseball dynamo who suddenly announces to the world that he prefers men to women as romantic companions. The media and his team go into a tailspin. Why has he said this? Davey Battle (Brandon J. Dirden), his best friend as well as the best player on a rival baseball team, urge him to tell his truth. Davey, a fundamentalist Christian, had no clue, and Darren learns how little he understood the man.

Patrick J. Adams and Jesse Williams.

Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

Lemming has led a golden life, untouched by racism, criticism or failure. He’s comfortable in the world as he imagined it, even after his teammates retreat from him and worry about showering. Then Shane Mungitt (Michael Oberholtzer) arrives, a Southern poor boy who has learned to hate anyone different. He spews out his contempt and disgust even as he elicits sympathy. Shane is a tragic figure. Abused by his father, an unwelcome foster child, close to being illiterate, poisoned by his social environment, he has one gift in a confusing world – pitching. His first suspension is for a stream of foul invective, but he is returned to the team, on probation. After Davey’s death, we find him in prison with little understanding of the seriousness of the manslaughter charge, begging to be returned to the team. Lighting designer Kenneth Posner boxes the stage in simple blue neon lines that he lowers so that the claustrophobia of the jail and of Shane’s new world are impressed on us.

Our guide through the play is Kippy Sunderstrom (Patrick J. Adams, even more charismatic than he was in the television series Suits, SAG award). Kippy and Darren are the smartest players on the team. It looks like a tight friendship as they offer support and share confidences but after the season, when the team has won the World Series, Darren closes down. And we feel it, the disappointment, the two men with different views of their exchanges and the world.

Patrick J. Adams. Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

Ironically, Darren’s deepest friendship is with Mason Marzac, his gay nerdy business manager (an appealing Jesse Tyler Ferguson). Mason went from little interest in baseball to pure, joyful obsession. His delight is in showing off his friendship with Darren to his pompous gay neighbors. They find in each a cure for their distinct loneliness. Mason has a long uplifting speech about baseball toward the end of the play that is luminous. It is bound to inspire new enthusiasts.

And then there are the other players. Takeshi Kawabata (Julian Cihi) who speaks only Japanese, and Roderiguez (Eduardo Ramos) and Martinez (Hiram Delgado), whose machine-gun Spanish Kippy sort of translates for us, making it up as he goes. Does he speak Japanese or Spanish? No, he says. But he understands both. And through him we understand also Takeshi’s isolation and the bond between the two Latinx players.

Scott Ellis, the artistic director of Roundabout Theatre Company, has awards aplenty but I left the theatre in awe of his deft gentle touch. For me there have been two Take Me Out experiences. One while I was in my seat, excited, engaged, and the one afterwards, now, when I can’t stop thinking about and admiring the play. It has a rare and terrible beauty.