Opera Ballet Vlaanderen, “Jenufa” and “Puur”

Dana Rufolo in Belgium

The two finale performances I saw on the weekend of 6-7 July, 2024 – Jenůfa in Ghent and Puur in Antwerp – have all the hallmarks – theatricality, vigorous and expressive dancing, operatic voices – of the extraordinary Opera Ballet Vlaanderen that I’ve written about in an earlier article even if Puur is in many ways a glorious failure. Acknowledging their intention to incorporate theatre into their performances, the Walloon opera and ballet company has invented a hybrid art of music, vocal, and dance performance. Their work is so original that it deserves a neologism even if for the time being I’ll assign their style the banal title of “theatrical ballet/opera”.

Jenůfa.

Photo credit: Annemie Augustijns.

In both Jenůfa and Puur, the theme is infanticide, but the manner in which each piece develops this term is distinctive. Leoš Janáček’s Jenůfa, performed at the Ghent Opera House with Robert Carsen as director, faithfully reproduces Janáček’s original Czech libretto based on the play Její pastorkyňa (Her Stepmother) by Gabriela Preissová, therefore avoiding ironizing contemporary commentary on the sexually and socially restrictive mores of the Moravian village in which the opera is set.

The intensely dramatic opera tells of Jenůfa who is loved by Lena, but she in turn is drawn to his half-brother Števa. When Števa discovers that she is pregnant with his child, he rejects her, claiming that her scarred face – for Lena has ripped her cheek with a knife – repulses him. The baby is born in secret; Jenůfa (the renowned Agneta Eichenholz, a coloratura soprano) loves the child, but her stepmother, the village elder, believes the baby is a burden. She tells Jenůfa that the baby died, but in fact she has murdered the child so that Jenůfa can have an unencumbered marriage with Lena who has proposed to her despite her newly reduced social standing. At their wedding, townspeople interrupt the ceremony to declare they found a newborn under the melting ice of the river; they are prepared to attack Lena when she says it is her child; the stepmother stands up and declares her guilt, leaving Jenůfa and Lena on an earth-filled raked stage romantically bathed in lights of the rising sun, she upstage and he crossing to protect her, so in the end love overcomes rigid thinking which masks the human need to be loved.

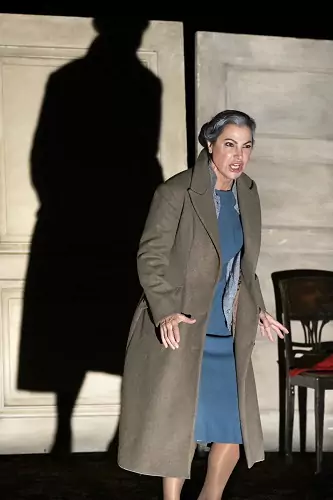

Natascha Petrinsky as stepmother prior to the murder.

Photo credit: Annemie Augustijns.

Of course, modern audiences will wonder why Lena’s knifing of Jenůfa is dismissed as inconsequential, the scar representing his claim to her but which by modern standards is an outrageous expression of possession. But the remarkable set which is nothing more than a soft fluffy flooring of rich brown earth and a set of off-white door and window panels that can be taken apart and rearranged to show either outside or interior scenes helps concretize the opera in a fairytale-like setting that successfully encourages the audience to experience the narrative without critical distance. Particularly striking is the scene when the villagers take hold of the door and window panels, and angle them menacingly towards Jenůfa as if they were weapons when they first hear that the dead baby is Jenůfa’s.

The highlight in Robet Carsen’s staging is the scene where Jenůfa’s stepmother (played by the strong mezzosoprano Nanascha Petrinsky) resolves to murder the baby. Initially the stepmother asks if she can merely go away somewhere with the child and Janáček’s accompanying music – under the baton of Alejo Pérez – gently reproduces the melody of a traditional European lullaby.

But then, as she concludes that it is impossible to let the baby live, initially the lullaby melody is distorted and then the orchestra simply transitions into loud dissonance. In this scene where musical and dramatic expressivity fuse, Petrinsky becomes more and more agitated; she is doubled in the form of long menacing shadows that play against the walls of her home; as she whips herself into a frenzy so as to do her unholy job, the shadows – so typical in German Expressionist films and plays – predominate. She is no longer in control of her actions.

This opera meticulously paints uneducated and unskilled Jenůfa into a corner from which marriage is the only possible escape. Laughter from teenagers in the audience is a not-surprising expression of contempt for the morally antiquated libretto, despite the passion and emotional richness of Janáček’s score.

However, by letting the opera play out its own truth, Carsen leads us to understand that ultimately it is Števa who is punished, as it is his child who does not survive. Števa, played with casual pomposity by the Czech tenor Ladislav Elgr, is a playboy bent on getting the most that he can from his chauvinist superiority, and therefore he selected the mayor’s daughter as his future wife, but it is clear from his puzzlement and remorse – as well as the initial duets that beautifully echo the attraction which is palpable between them – that he had counted on Jenůfa’s shame and maternal instincts to keep the cuckoo in the nest. His fiancée rejects him once she knows the truth, but meanwhile Lena’s non-judgemental devotion to Jenůfa implies that theirs will be a happy and fruitful union.

Although the opera is outdated and its themes of sacrifice, punishment and redemption sit very much within the Christian tradition, the music remains awe-inspiring. By retaining the anachronistic integrity, the production gained an emotional hold on the audience because the conflict between men and women due to fundamental biological differences has yet to be resolved.

~ ~ ~

Puur, meaning “pure”, a dance theatre piece choreographed by Wim Vandekeybus, ostensibly starts from the biblical story of Herod ordering the execution of all the two-year-old boys in the city of Bethlehem because he has been told that one of them is going to grow up to usurp his power.

The piece veers into a story of one of the male dancers enduring his father’s disapproval and rejection. The hybrid work incorporates dialogue and film (slightly blurred scenes showing babies and their mothers which are meant to represent the babies whom Herod’s men slaughter) into masterfully emotional athletic dance scenes that take place within a fence of thin sticks that encircles the stage.

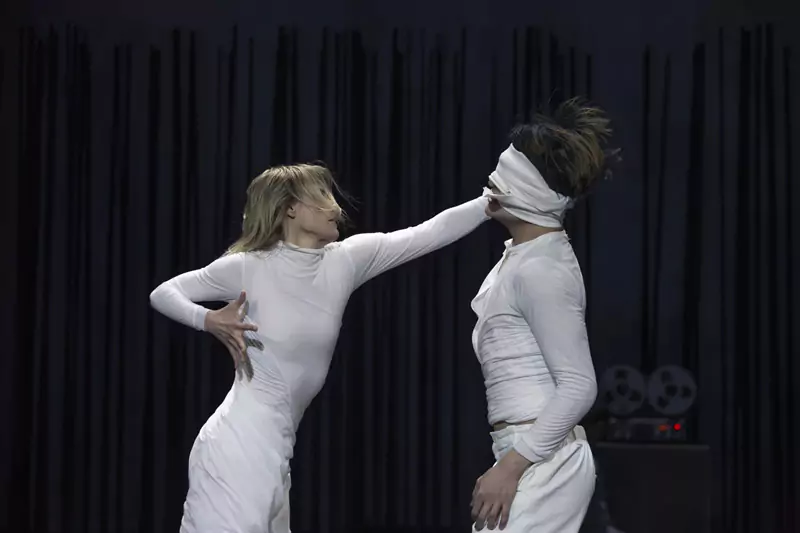

Puur.

Photo credit: Danny Willems.

In a striking opening number, the dancers on the floor are subjected to some sort of spray from a cannister, and they twist like spiders or beetles away from the source of irritation into clusters. This introduces the dancers as the murdered children who are grown angry beings who re-enact the cruelty they suffered when babies and alive – the most extreme acts of cruelty include suffocation and spitting liquid into one another’s mouths. This to music by Fausto Romitelli and rock songs from David Eugene Edwards.

We depend on notes in the programme to understand what is going on since it is not evident that these dancers are resurrected grown children; the confusion is intensified because they are both men and women whereas Herod had singled out only boys. The dancers are so amazingly flexible (again, Lara Fransen stands out) that even though they might be symbolically impaling one another on thick white arrows or engaged in stick fighting, their dance aesthetic keeps the images they transmit bloodless and graceful. The anger they are supposed to be feeling is, also, subsumed by the demands of their craft.

Puur.

Photo credit: Danny Willems.

In Puur, Vandekeybus – who is working with the Opera Ballet Vlaanderen for the first time – declares war on his own art form. His is an experiment and it has the bravery of one, even though the result is a hodgepodge. My impression is that he is radically disengaging from clear narrative structure because structure generates wars, infanticide, and so forth.

But more is needed; he must develop a language and choreographic style that remoulds the artist who plays in the melting pot of physical movements into an engaged artist who is sensitive to how his danced tales are received by the audience. I say this because in the performance I attended, the audience did not view the piece with rapture. We were embarrassed by the disparate elements in it that interrupted our ability to absorb meaning – even the poetic meaning of dancers who sculpt the fluidity of movement so forcefully. We were confused by the indistinct video images of crying babies and the many anti-dance elements in the performance, including a dancer who was totally nude, through no wish of his own I felt. He was obliged to stand naked on stage as his father, an actor with a beard, a belly, and an American accent (Daniel Copeland), says, quite unemotionally, “I wish you were never born.” By the way, the correct English phrase is, “I wish you had never been born.” Hung up on the additional hurdle of hearing inexact English, I was impeded from reacting as intended – which was to fall down the rabbit hole of shock and pity. But developing the codes for a danced performance piece that engages with contemporary political and social concerns takes time, and it is likely that Puur is just the first step on a long journey.