“Petroesjka” and “Die Sieben Todsünden”, Opera Ballet Vlaanderen

Dana Rufolo in Antwerp

February 2024

Imagine you are not on this earth and yet you are in a theatre, and you will grasp the impact of the Antwerp, Belgium production of the oneiric Petroesjka with Igor Stravinsky’s score and original choreography by Ella Rothschild along with Die Sieben Todsünden, a Bertolt Brecht-Kurt Weill danse chanté from 1933.

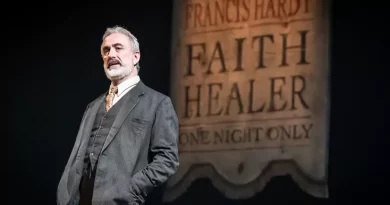

Ensemble for Petroesjka with puppet by Jan Maillard.

Photo credit: Filip Van Roe.

The Opera Ballet Vlaanderen’s journey to the centre of deep imagination is a daring depiction of the company’s “mission” to “focus on hybridity, or the cross-pollination between our two primary activities, ballet and opera,” according to its artistic director Jan Vandenhouwe. It is one more example of what seems to be a delightful new trend in Europe: the Theatrical Opera. I have covered two examples of theatrical opera productions in La Clemenza di Tito and The Carmen Case. And there is in this double bill an additional surprise element: the scenography (signed Eva Veronica Born), which plays a central role in uniting both productions into two distinct parts of a whole.

Taking up the topic of the scenography first, what we see when we enter Antwerp’s Stadsschouwburg Antwerpen and are awaiting Petroesjka is an otherworldly stage environment. It is a simple undulating space, with two elevations that could be called dunes, one stage rear and on the audience’s right and the other on its left which is slightly flatter and of the two is far more actively in use as a hillock for the dancers to move across or stand on. To call these elevations ‘dunes’ is not inexact, because it proves to be a desert-like environment even if the dominant colour is dull white rather than yellow. The matted white material we see covering the stage might be dried grass, but just as easily we can imagine it as an unknown matter in a mysterious landscape – onto which the dancers bring a few tufts of short reeds.

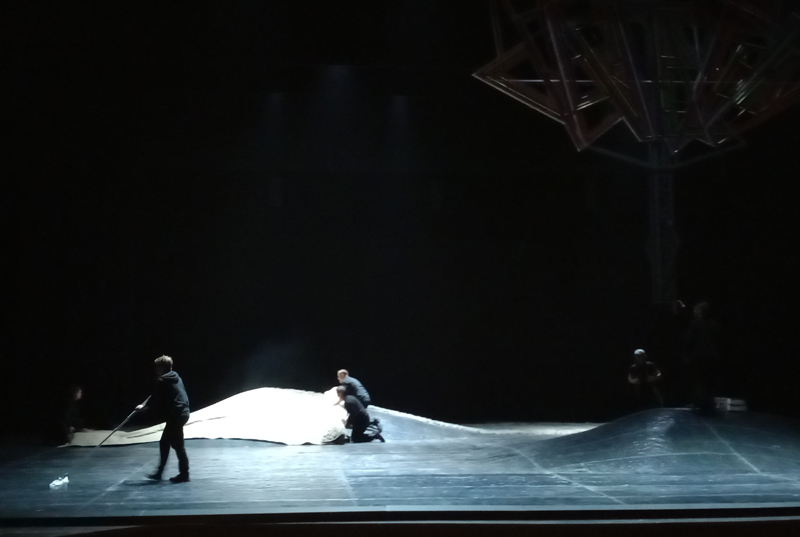

The surprise is that this very same undulating stage floor, without the white matted substance, is transformed into the stage space for Die Sieben Todsünden (The Seven Deadly Sins). Stage hands roll up and away the pale matting to reveal an undersurface of something like bitumen (the informative and well-researched theatre programme (advertisement-free) states that it represents “the shiny asphalt and neon lights” of Brecht’s anti-capitalist spoof). Add a pillar of neon tubes that turn into glowing letters and form words and, voilà, the space is now fit for Brecht. This transformation takes place during the entr’acte and is a performance in itself as illustrated. See photo below.

Stage being transformed for Die Sieben Todsünden.

Photo credit: Axel Hörhager.

The original Petroesjka told an entirely different narrative; it was developed in 1911 for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris; Vaslav Nijinsky danced the title role of the puppet Petrushka which is equivalent to Punch in the British puppet tradition. The folkloric puppets are the focus of the action in the 1911 original and humanity is the focus in Rothschild’s work, so there is little similarity with the original except for Igor Stravinsky’s score.

Petroesjka is a danced mime. I report on the narrative I read into the performance, which differs from the one that Rothschild considers herself to have choreographed. In her interpretation, the crowd (the company has 18 dancers) that moves from the audience’s right across the front dune diagonally is sinful mankind; one of their own – the Mortal – dies and is resurrected, offering hope to the crowd of sinners.

What I saw on 27 January, 2024 was a throng of dancers who seemed to be a group of gesticulating, emotionally expressive and perhaps silently wailing people, a kind of clan, not necessarily all of humanity or humanity’s representatives, slowly moving forward into an unknown future. For me, the Mortal never really dies but rather goes dormant. This is because although his body is batted about by the others, it responds to the laws of gravity all the same, and for brief seconds appears to be standing on its own in a way that a truly dead body cannot do, or so I intuit. There is life in that corpse yet! So, it is not surprising that rituals of first aid revive the mortal being, and he returns to life.

Ensemble for Petroesjka.

Photo credit: Filip Van Roe.

The visually striking arrival of the seven-part animal identified for us as a donkey (see top image) which is off-white in colour, each part appearing to be made from some kind of matt plastic material, is breathtaking. Rothschild likes to work with puppets, and the pale donkey is classed as a puppet. Not, of course, the doll-like and folkloric puppets of the 1911 Russian Petrushka but a vaguely familiar yet curiously beguiling creature that contributes to the dreamlike elements of the performance.

Symbolically, the animal parts are repeatedly separated and reassembled by the seven dancers holding them; I assume that this is meant to parallel the solidly united and yet individually composed quality of the crowd itself, although honestly what we saw was so striking that there was no need or time for the imagination to search for intellectual interpretations. Ultimately, the animal parts fall to the wayside, and after a while one of the crowd places the head on her shoulders. The overall impression is that we have collectively witnessed a gathering of humanlike creatures who have shared emotional experiences and are seeking for meaning (and to a certain degree finding it) in a landscape that has not been burdened with the architectural characteristics of any one specific civilization. They are performing for our benefit; in some mysterious passive way they feel love for us.

Alejo Pérez conducted the Symphony Orchestra of the Opera Ballet Vlaanderen to play Stravinsky’s extraordinarily expressive music featuring its signature bitonal chord, with sensitivity and lightness, interpreting it as a more centred piece than is usual with its Sforzandos softened and milky so as to coincide with rather than distract from the dramatic choreography. This work is credited as being the first modern piece of the twentieth century, setting a new post-classical standard that allowed for composers like Kurt Weill to feel confident about marrying high and low-culture musical genres.

Fox-trot, waltz, barbershop quartet, church chorale, cabaret, operatic aria: Weill incorporated an eclectic range of musical styles into his 1933 composition of The Seven Deadly Sins so as to satirically critique the money-obsessed aspects of American capitalism. The orchestra, also under the baton of Pérez, played with verve and vivacity, keeping the tempo quick and upbeat. A fusion of dance styles in this performance complements the musical mixture of styles.

The cast of dancers and the principal characters, two Annies, sisters (Annie I who sings is the manager and Annie II who dances is the artiste) whose talent is for sale. They are clad in virginally white dresses and travel around the United States visiting the seven largest cities so that dancer Anna II can earn money to send back to their slobby and lazy family of two brothers and parents in Louisiana.

Lara Fransen and Sara Jo Benoot in Die Sieben Todsunden.

Photo credit: Filip Van Roe.

After seven years of wandering and cashing in while ultimately avoiding committing the seven deadly sins, the girls amass enough money to purchase a family house to which the whole family can retire. It is a simple morality play lacking the brilliant one-liners of Brecht’s best works, but the spoof of capitalist values is immensely seductive, as is true of Brecht’s work in general. One yearns to ridicule capitalism under Brecht’s influence. However, the irony that will not go unappreciated by all who are currently struggling to purchase property, is that the sisters’ ultimate goal is to retreat from the consumer society that solicits the sins of sloth, pride, wrath, gluttony, lust, avarice, and envy. All they want is a little home to call their own.

The choreographer Jeroen Verbruggen sees the Annies as the same person split into commercially-minded and idealistic selves, and the text supports that interpretation when Annie I sings:

“You may think that you can see two people/ But in fact you see only one/ And both of us are Annie:/ Together we’ve but a single past, a single future/And one heart and savings account;/And we only do what is best for each other/ Right, Annie?” (Translation by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman). In the 1930s, the notion of a split personality must have been tinged with the exotic; Sigmund Freud was just developing his tripartite concept of the personality, but nowadays artists are obliged to have a commercially-minded side to them. Just consider the title of a book published in 2024: Acting is Your Business.

Lara Fransen, the petite modern dancer in the role of Annie II, is extraordinarily fluid and stylistically flexible; her long list of prizes shows she is being noticed. The mezzo-soprano Sara Jo Benoot as Annie I sings a cappella, pronouncing Brecht’s words in German sweetly and distinctly.

Teresa Vergho’s exaggerated costumes for the family members, each turned into obese waddling Americans, play up to Brecht’s satirical script. Abiding by the score in having the mother’s role sung by a bass, in this performance Manuel Winckhler, reinforces the grotesque humour in the song and dance piece. The Opera Ballet Vlaanderen dancers accelerate the action with their gymnastic movements. They transform from one support role to the next instantly and surround the two Annies on every stage of the seven-part journey. The tower of neon tubes is lighting designer David Stokholm’s contribution to Born’s stereotyping of glitzy Americana that Brecht exposes here, as he did also in The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.

Together, Petroesjka and Die Sieben Todsünden by the Opera Ballet Vlaanderen are an evening of theatrical opera of unforgettable playfulness and originality. We the audience are privileged to escape from our social world stretched to bursting by anxiety, pessimism, cruelty, and dysfunction; we fall down the rabbit hole into a place of radiating human imagination where life is pulsating with the energy of resurrection.