“Minority Report” at Lyric Hammersmith

Simon Jenner in west London

3 May 2024

A story by American sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick isn’t the first adaptation you would think of from dramatist and actor David Haig. But he delights in being stretched and given a free hand. His Minority Report plays at the Lyric Hammersmith (in a co-production with Nottingham Playhouse and Birmingham Rep) directed by Max Webster until 18 May.

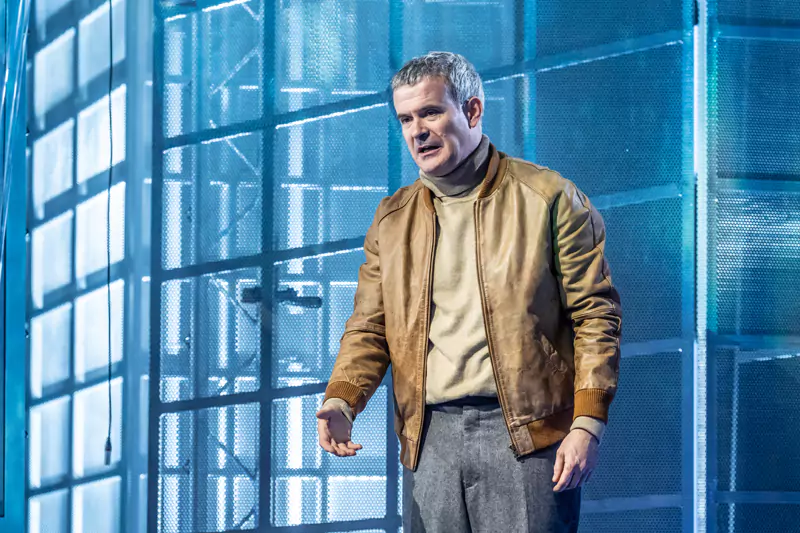

Nick Fletcher as George.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Dystopias projecting one strand of a possible future have gained popularity in a world of AI and advanced medicine. Haig has freely adapted Dick’s 1956 novella. It’s now 2050, where for a decade “Pre-Crime” enforcement in the UK has prevented anyone in a universally chipped population from committing any crime.

It’s the brainchild of (now Dame) Julia Anderton (Jodie McNee) who walks on confidently to lecture us with a bucket. You guess what it contains. Eight years ago her twin sister Laura was the only person ever killed since this new system was enforced, and Julia is adamant Laura’s legacy will be preserved. Yet Laura’s killer has never been caught.

Danny Collins’ “Pre-Crime” protester Fleming (ever in a woolly hat, a uniform shorthand) disrupts and is brutally ejected. But Julia will need him later. She’s about to read out the name of the next person wholly unaware they are about to commit a murder, who will be hauled off the streets and incarcerated, perhaps forever.

Trouble is the next name is hers. McNee excels at confidence twisted to outrage and collapses. Back in her room Julia then accesses her personal AI David (Tanvi Virmani, appearing with some personal agency towards the end) who plots a mode of escape. Julia has to tear out her chip and make a getaway, even as her husband George (Nick Fletcher, a nuanced bundle of bumbling intentions) and the home secretary, old friend and Laura’s former lover Ralph (Nicholas Rowe, horribly smooth and placatory), plead with her to surrender till there is clarity to this mix-up.

Set in a real time of 90 minutes it’s clear that pace and clarity score over shades of character; several of the cast multi-role. This isn’t a character-driven play, but a scorching moral poser with no easy answers.

Ricardo Castro, Jodie McNee and Xenoa Ledgister-Campbell.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Julia is determined to get answers though, certain she’s been framed (real confirmation bias there). The answer resides with anonymous “Pre-Cogs”, those who voluntarily surrender their time and biology to deliberate each brain scan for guilt; they have never been wrong.

What follows is in some senses the star of the show: a set which should be up for next year’s Olivier Awards. Jon Bausor’s steely construction morphs from tech interiors to a receding block of gleaming flats, as taxis swallow up, disgorge, otherwise judder to a halt. It’s also served by a descending/ascending gantry: this allows scenes of escaping above along a ventilation shaft, or creeping below in one as police swarm above.

Jessica Hung Han Yun’s lighting infiltrates and exposes dingy hideaways as well as glaring citadels. Tal Rosner’s video design superimposes, creating projections from brain scans to David’s avatars, through other effects that render this whole spectacle one of the most satisfyingly realized futures I’ve seen on stage. Nicola T. Chang’s score and sonics thrill: sound is imposing, not deafening.

Though spectacle could potentially overwhelm acting, Lucy Hind’s movement and intimacy direction ensures protagonists fling themselves across the stage in bewitchingly energized blocking. They prove the most kinetic agents of a vast set. They are never swallowed by it, almost urge the whole stage forward.

Though momentarily recaptured, Julia’s aided by Fleming and meets his companion Italian Ana (Roseanna Frascona), who is allowed the most humane performance of the show. She details her trafficking and loss of a child as well as ostracism. It’s not germane to the plot which is why it works.

Gaining access to an office Julia learns from her “minority report” a possible answer, encountering former student Christina (Chrissy Brooke) who like Ana, though far more briefly, registers the human cost of being co-opted in a very different way. Every exit seems blocked, principally by Ricardo Castro’s brutish Sergeant Harris, allowed a truculent line in truncheon humour.

There’s a caricature role for Xenoa Campbell-Ledgister who as US corporate-broker Michele is only too keen to replace Julia. Michele has dealings with Ralph and – could it be poor neglected George has done something unexpected? Who can Julia trust? Her former antagonist Fleming?

Haig has satisfyingly reworked Dick’s fable into a tight script: answers are as complex as they are perennial. If you could prevent any crime by arresting people before they offend, would you do so?

Ralph notes with Julia in an earlier rapport that one in a hundred of convicted people being innocent is a price worth paying. And should people be punished for a crime they have only thought of? Dick must have recalled 1984’s Crimethink and terms of incarceration here (do they all get life? Some clearly serve at least ten years) isn’t broached.

An overwhelmingly realized thriller, an extremely active cast urges questions, even as the spectacle urges you to lean forward for answers only storytelling lends.