The Shakespeare Lady

Robert Schneider on Margaret Holloway.

20 June 2020

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel tells us that certain lives have world-historical importance; certain individuals introduce energies and ideas to the world that resonate in the moment and mark it forever, whether for good or evil. The world-historical individual might be fully conscious, partially conscious, or wholly unconscious of embodying the historical moment. I would like to nominate Margaret Holloway for the last category: a world-historical individual of no importance, a marker in the dark liquid of Covid, a grain on which the hopes and contradictions of our age will slowly crystalize.

I first encountered Margaret Holloway when I attended the national conference of Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas in 1997 in New Haven, Connecticut. The conferees, all connoisseurs of theatre and performance, had taken a bus to the outdoor Mystic Seaport Museum for a farewell dinner. The return buses dropped us off in front of the Yale Drama School, which was hosting the conference. On the sidewalk in front of the building stood a tall African-American woman of indeterminable age, invested with immense corporal dignity. She was wearing a shapeless black sweater over dirty and torn pants but carried herself as proudly as Hecuba might when challenging Odysseus.

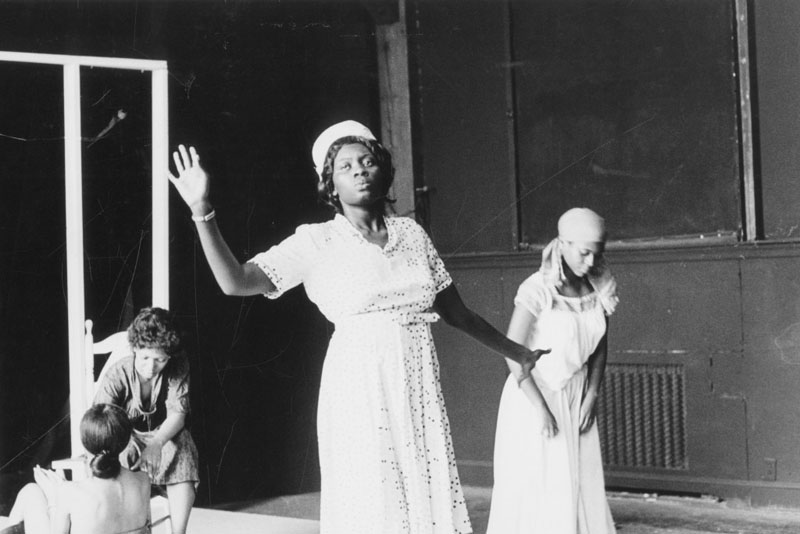

Margaret Holloway in Recipe at Bennington College in 1974.

Photo courtesy of Bennington College.

“Would anyone like to hear a recitation from Shakespeare or the classics?” Her voice was even and low, with no trace of dialect. There was coolness to it — and perhaps an edge of menace. It was, in fact, General American Pronunciation, the supposedly class-neutral speech that acting students are taught as a way of banishing regionalisms from American productions of classic plays. It was unsettling to hear it from a homeless person. I felt a chill, as if watching something that defied gravity, my unacknowledged notions of caste justice profoundly shaken. The dramaturgs and literary managers of the Americas filed past her like sheep in loading shoot, eager to reach the safety of the building.

Their behaviour seemed bizarre to me even at the time. Drama people say they’re addicted to stories and always look for a good one. Literary managers, especially, relish the many flavours of dramatic irony and train themselves to be connoisseurs of cruel fate. The shocking dissonance between the woman’s appearance and her voice was intriguing; would it have hurt to ask the woman for a recital? Mightn’t someone at least ask what she proposed to recite?

Margaret Holloway repeated her offer in a somewhat louder voice, waited a moment to confirm that nobody would take her up on it, and then strode up York Street toward Broadway with a bit of haughty distain in her stride.

Of course, I was no better than my co-conferees. I’d come back on an earlier bus and was watching from a few yards off, but I could easily have approached Margaret and given her a few dollars to perform. I’m sure the other LMDA members would have stayed to hear her. Lord knows the outdoor dinner had been a washout; here was a chance to salvage the evening. But I stood there like a post. Looking back on it, I realize why we had all declined: Margaret Holloway was frightening.

Because I lived in New Haven, I had other opportunities to hear her recite. She was often in front of Willoughby’s Coffee & Tea Shop on Church Street. Her acting was declamatory, intense, almost spasmodic – a style that cherished individual syllables and wouldn’t let them go. She liked to do Medea’s last speech to Jason but also the witches from Macbeth and Ariel from The Tempest, characters that were possessed themselves as well as being agents of possession.

Margaret Holloway at Bennington College in 1974.

Photo courtesy of Bennington College.

I managed to find out more about her. She’d spent a year at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota before discovering theatre and transferring to Vermont’s Bennington College. A faculty acquaintance who knew her then said she had extraordinary talent. Later at Yale Drama School, Robert Brustein allowed her to triple-major in acting, directing, and playwriting. She graduated with an MFA in 1980. The locked cage in the Drama Library contains her thesis; it includes a skimpy rehearsal log of her final production with comments that don’t say much. One of them read “the rehearsal process is continuing normally”.

By 1983 she was on the street. Pam Jordan, the Drama Librarian, told me that Holloway used to sit in the library and stare fixedly at other patrons until Pam asked her to stop. Pam said she’d become an addict and got disability payments from the state. Pam was amazed that addiction counted as a disability, but apparently it did. Holloway was in and out of the psychiatric ward at Yale-New Haven Hospital and did several stints in jail. Between times she acquired a reputation as a street performer. She played down to her audience, flipping out the antique words as if she owned them, or as if the words themselves owed her service and obeisance. Performing on street corners, she had little use for subtlety – presence was her strong suit. When she declaimed, people listened. Students called her “the Shakespeare Lady”.

In 2004, William Yardley, a journalist for The New York Times, reported that she was occasionally aggressive. Yardley quoted a Church Street bartender, Pete Pereira, who said, “If she conducted herself the way she did five years ago, everything would be fine, but she just badgers you. My buddy paid her $50 once to be left alone for a year”.

The New Haven Register reported that Holloway stopped using drugs in 2008. She told the newspaper she’d gone cold turkey. She’d also given up panhandling and moved into a small apartment in a building owned by a non-profit organization.

On 4 June of this year, Margaret Holloway died of Covid-19. Her own mortality can’t have been news to her; she’d memorized too many classic texts on the subject. At some point, however, she must have been astonished to learn that even the young and talented are subject to madness. It was a revelation to me when I first met her the night the dramaturgs shuffled off their hired bus. Like Laertes, l wondered: “ls’t possible a young maid’s wits / should be as mortal as an old man’s life?” But Ophelia wasn’t one of her characters.

I’m told she had a number I never heard; she would act out the Greek alphabet as if she were leading cheers. This year she came to her own omega. Richard Dailey made a short film about her which concludes, “Margaret was stricken with a rare form of schizophrenia and has been homeless since. One must wonder how such a problem is allowed to persist in the most powerful economic country in the world.” For thirty years, Margaret Holloway embodied the zeitgeist of downtown New Haven – and perhaps of grittier cities everywhere. l hope that, world-historical individual or not, she has no understudy waiting in the wings.

Margaret Holloway in later life.

Photo courtesy of Robert Schneider.