“La Traviata” at Opéra Bastille

Yann Messager in Paris

19 February 2024

Simon Stone’s Traviata, with gripping musical direction by Giacomo Sagripanti, is a grandiose transposition of the mythical Parisian story unto the intricate workings of twenty-first-century ostentation. A quite literal but brilliant materialization of digital life has a stage-width three-sided cube as the main set piece for the entirety of the play, the screens of which become backdrops or social media flows. This Traviata project originally opened in 2019. Nadine Sierra’s Violetta Valéry (we encountered her recently in Marina Abramović’s 7 Deaths of Maria Callas) is the ultimate social media diva of the age, an influencer reaping all conceivable advantages from a Paris focused on luxury. Immediately we are transfixed by the massive eyes on both sides of the cube’s rim which create an eerily ominous face, for its perceptions and scrutiny is the all-seeing eye of social media which ultimately pushes and pulls our characters from beginning to end.

Photo credit: Vahid Amanpour.

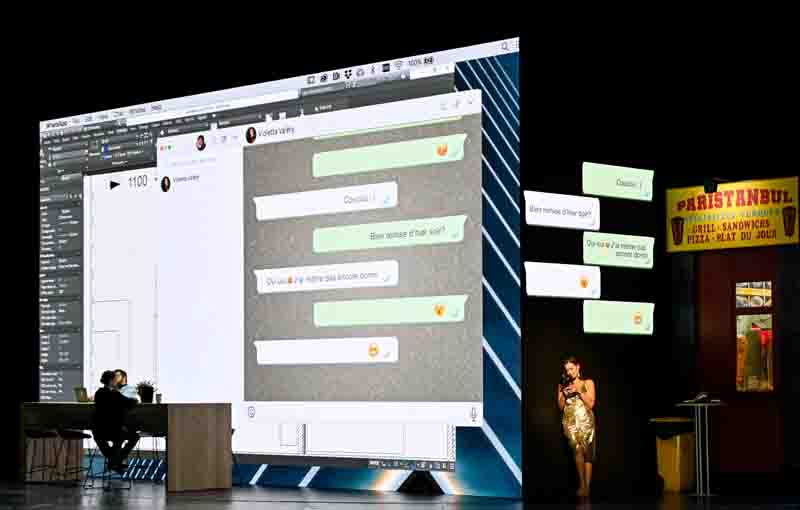

Stone’s Traviata boldly embodies spoiled courtship rituals in the wondrously lurid Paris of set designer Bob Cousins. Whether it is Nadine Sierra’s Violetta sauntering in front of a long queue at a night club, ordering a midnight kebab or texting René Barbera’s Alfredo who answers from his upbeat architecture practice, the artistic director’s eye for evocative detail sublimates this nineteenth-century century piece into a shockingly prescient in our times.

The vast cube goes from originally being the odd classicist’s nightmare to a successful approximation of the conscious experience of digital life. Its sheer size both gives the spectator (be they far or near) the impression of scrolling on one’s own device while also allowing for snippets of digital communication to erupt onto office or kebab house walls, countryside havens or orgiastic palace chambers. The perpetually rotating cube around which Violetta seems to endlessly walk gives off the impression of a true stroll through the underbelly of the appearance industry.

Sierra’s Valéry then becomes the ephemeral glance of extravagance for the average Parisian frolicker, the black-dress donning youth one catches exiting through a back door of the Lutetia Hotel instantly hopping onto her lover’s motorcycle (truly witnessed here), leaving one with fleeting questions as to the mechanisms of the modern influencer’s reality. Stone shows us one where dreams beget more dreams in a phantasmagorical nascent industry where our characters themselves are tricked by their own illusions. They cling magnificently but gaudily at their own deceptive perfection. The vast and iridescent world allowed by pixels then becomes a more sophisticated mirage, replete with movement, dance and colour, the blue humming lights that accompany Sierra until the very end.

The grandeur of scenery and cast supports this larger-than-life story whether through the Dionysian scenes where hundreds fornicate on sports cars or wear sexually suggestive costumes which sometimes confound the imagination. For this gilded pomp seems to ask of us the perpetual question of what it is we do when we dive into the city.

Photo credit: Vahid Amanpour.

The massively orchestrated parties beckon to an idea that in Valéry’s dance through the haze of it all, in the endlessly crumbling human mountain of pride, she becomes only a mere modern archetype. Simon Stone seems to brilliantly make the piece less about her being a “demi-mondaine” by discovering in the influencer or ‘creator’s’ economy the more adequate contemporary equivalence.

This is one in which the rise of digital civilization has not quite opened the floodgates of social hierarchy but rather made it apparent how asphyxiating they continually seem. Few are the YouTubers who become Hollywood talent, few are the influencers who attain journalistic prestige. Instead, Stone’s Traviata confirms the Icarian tragedy of manly ambition in which the Greeks warned of the terrible fate reserved to those who do not “know their place.”

Social media is fascinating perhaps in that it leaves a record of this epic, everlasting brawl, of men trudging along their entire lives while being bogged down by immutable sociological forces. It is suggested that nothing really differentiates us from one another, and from that sometimes frightening truth we recoil to spend our lives trying to prove ourselves otherwise, and often with tragic consequences. Shuffling and reshuffling superficiality here, brushing and re-brushing streaks and highlights there, never to truly confront the realities of our inner desire.

In a perfect aesthetic conclusion, we look on as Violetta dies by leaving her hospital bed and entering the breached part of the cube via a white mistiness, finally devoured by the very digital beast she thought she could trifle with. No longer is she a victim of the now blatant social absurdities of Old Europe but rather the victim of how we endlessly find ways to reshape our societies, merely translating our seemingly forlorn woes into new, shinier alternatives. Stone delicately makes Sierra’s Violetta a heroine for modern times.