Tehran: State of Theatre

Mohammad Reza Aliakbari in Tehran on the State of Theatre in the Nation

Evidence from Iranian life shows that professional theatre in this country has a murky perspective. This is not only due to the global crisis of Covid-19 but also because of economic and social crises that have deeply affected all aspects of Iranian life since 2018. US sanctions against Iran have had a devastating effect on the existence and future of the people rather than on the ruling regime. Delayed Covid-19 vaccinations have also suspended or significantly slowed the usual channels of social and commercial activity. The theatre has suffered irreparable damage in such circumstances.

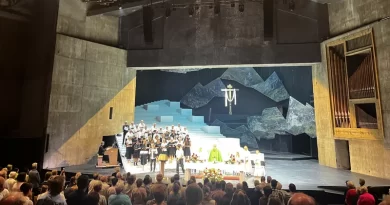

Tehran City Theater.

Credit: Fars Media Corporation.

From the beginning of the pandemic, announced in Iran in February 2019, until today, the fundamental question under discussion among theatre practitioners is whether theatre, which was not an Iranian tradition but resulted from the importation of Western theatre traditions, has any meaning for the Iranian public; did they miss theatre during lockdown? Familiarity of the Iranian intellectual community with the Western form of theatre began nearly 150 years ago when the first groups of Iranian students were sent to Europe. They brought back plays by Shakespeare and Molière and other European classic dramatists, and their knowledge of the concepts and norms of modern European societies eventually led to one of the first efforts in the Middle East to establish the rule of law and democracy: the Constitutional Movement which will be celebrating its one hundred and fifteenth anniversary this summer. And yet, despite this history and the efforts made in the 1960s and 1970s to open the cultural gates of Iran to the rest of the world as seen in the eleven editions of the Shiraz Arts Festival (from 1967 to 1977), today it is questioned whether the theatre really has a social meaning for the people or not. Does the cessation of theatrical activities cause concern among the part of the society that had been the theatre audience?

It seems that regardless of the government’s position on theatre, there is a lack of interest in theatre; its apparent lack of roots in Iranian society is a source of frustration and disappointment for Iranian theatre professionals. The government has always been involved with theatre as a cultural activity of social import, but during the last 43 years since the revolution, Iranian theatre has been in conflict with the government due to its religious ideology and its ambiguous attitude towards the performing arts.

It should not be forgotten that Iranian theatre and familiarity with western theatre are manifestations of the Enlightenment that led to the Constitutional Revolution. Moreover, of course, when prior to the Iranian Revolution that made Iran an Islamic Republic the intellectuals had called for secularism and a separation of politics from religion, the clergy resented the attempt to side-line them, and so when religious figures decimated the constitutional movement and finally came to power in 1979 in a country that has continued to this day, the attitude that theatre is somehow tainted by association and merely tolerated became dominant.

The Iranian cultural and intellectual community, frustrated by Hassan Rouhani’s eight years in office, is now facing a new government that will suppress the cultural landscape. The economic consequences of the pandemic — along with the devastating and profound effects of the American sanctions and the political crises of domination at home and in international relations — promise years in which theatre will not flourish (I can only hope my prediction is wrong). It is not without reason that

many actors and writers in the current Iranian theatre scene have migrated to working forTV series: superficial programmes that are nothing but vulgar entertainment and exist solely for the reason of capital turnover.

Qom City Theatre.

Photo credit: Mostafa Meraji.

It seems unavoidable that during the next four years, the Iranian theatre will be almost empty of its former professional forces. On a positive note, this may well provide an opportunity for young people whose motivation and enthusiasm outweigh economic requirements. The young and intelligent forces, who did not have the right

space to attend and grow, now have a field that can interrupt the horrific capitalist cycle that turned Iranian theatre into a mere entertainment industry in the past decade and create a new path forward.

Indeed, at a time when some theatres have reopened with the permission of the government, we see that the pioneers of the performances are young people who have not given up trying and rehearsing over the past year. Of course, the auditoria have few spectators; however, this is just the beginning.

The government has not announced a clear policy towards resuming theatrical activities nor any form of support for the theatre, leading to Iranian theatre

practitioners making comparisons between their situation and theatre policies in other countries. Although this comparison is inevitable, the contextual conditions are not. The speed of vaccination, the existence of long-term planning and economic support of developed countries, along with constructive international interactions, are issues in which Iran differs. In addition, this discrepancy exists while the rise to power of a faction with more extremist religious views obscures the perspective of the Iranian society and its cultural manifestations. We have to wait, and of course to hope …

Qom City Theatre.

Photo credit: Mostafa Meraji.