“Giulio Cesare” at Glyndebourne

Simon Jenner in East Sussex

19 July 2024

“Is there a serious production of this?” asked one audience member en route to the coach after Glyndebourne’s revival of David McVicar’s 2005 Giulio Cesare by Handel which continues till August 24th conducted by Laurence Cummings.

Svetlina Stoyanova as Sesto.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Difficult to say, even roughly transposed to an Egypt under British occupation in 1890. Handel was possessed of so much humour that McVicar effortlessly taps into the vein, in what is undoubtedly one of Handel’s greatest operas. And most successful. One contemporary said: “The house was just as full at the seventh performance as at the first”. Dating from 1724, it’s also the first of Handel’s great trilogies – Tamerlano and Rodelinda followed. This year marks its tercentenary.

It is, needless to say (though not for the lady on the coach) deeply serious and no more so than at the ends of Acts One and Two where real tragedy strikes and never completely evaporates. And there is a particular delight in this performance: the second of two in which BBC New Generation Artist Johanna Wallroth replaces Louise Alder as Cleopatra, herself receiving five-star reviews. On this performance Wallroth too isn’t so much poised for stardom as leaping into it.

Danielle de Niese was famously a singing, dancing Cleopatra in 2005, and McVicar has returned to direct this production. Choreographer Andrew George crafts routines in which principals and ensemble members conjure up (our notions of) Egyptian movement and dance. Cleopatra and her confidante Nireno prance a hornpipe at one point.

Redesigned by Robert Jones as a restrained recession of neo-classical pillars with various backdrops (sea in baroque style, and a huge map screening off the depths on occasion) the set acts as a foil.

The visual star is Brigitte Reiffensteul’s striking use of red uniforms, pith helmets and late- nineteenth-century baggage that contrast with occasionally gorgeous moments, such as Cleopatra bed-bathing in a discreet flow of silver silken sheets. Or a feast of blue and violet curtains with Paule Constable’s lighting casting shadowy doubt or seduction, until suddenly blazing noon at the climax. The whole stage bathes in daylight. It’s a striking transformation.

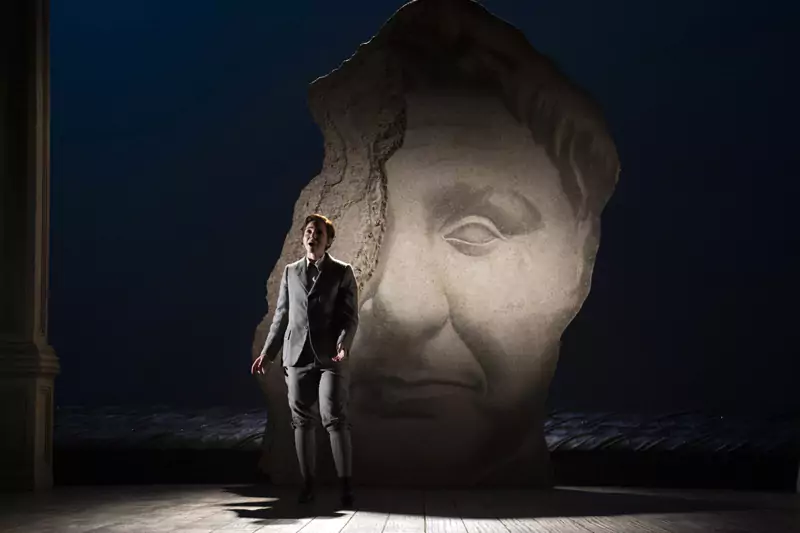

Cameron Shahbazi as Tolomeo.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Though Cesare (Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen) is central to Handel’s and librettist Nicola Haym’s conception, they divide interest equally between him, Cleopatra and widowed Cornelia (mezzo Beth Taylor) and stepson Sesto (mezzo Svetlina Stoyanova). They’ve been bereft of husband and father respectively, Roman Pompey: whom Cesare had beaten but would spare.

In vain. Scheming Egyptian general Achilla (a superbly inky basso Luca Tittoto) conspires with Cleopatra’s spiteful younger brother Tolomeo (a memorably petulant Cameron Shahbazi) to ingratiate themselves by presenting Pompey’s severed head. Big mistake, but interestingly drawing a parallel with another British (aka Roman) General Gordon who was beheaded in Egypt in 1885.

Cornelia faints. Though this is a parable on imperialism, it’s not literal: Cleopatra when she flies in as a flapper in a little black number, sets off a different but still imperialist culture. Indeed even the ships change. Cesare arrives with tall ships, but Cleopatra’s aria “Da tempeste” is sung against a backdrop of proto-dreadnoughts, even dirigibles, and a baroque wind machine lurks too.

That is not the end of Cornelia’s troubles, as first Achilla then Tolomeo fancy her for themselves. Using wisps of history as a springboard for amatory court intrigue informs nearly all Handel operas; but here there’s a little historical support for it. Perhaps this audience member, who quoted the English of “Veni, vidi, vici” was hoping for more bodies.

Again, this production doesn’t flinch from throat-cutting of British-Roman soldiers as they sprawl defeated. McVicar’s production is alight with deft touches of wit and fun, ironizing the opera seria side when it threatens too much pomp. None more so when bloodied and dead, Achilla turns up at the final celebrations and mutely demands a share in the toast to the victors, until he is given a glass.

Stoyanova’s Sesto strains at the leash of adolescence, but Tolomeo is no older. All Sesto’s arias are minor-keyed revenge ones, save in duets with Taylor’s Cornelia. With a flexible, light-toned brilliance Stoyanova’s finest is perhaps the ferocious triumph of “La giustizia” slaying Tolomeo.

Beth Taylor and Svetlina Stoyanova.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Shahbazi’s final aria “Domero” allows more reflective angst than previously, and again he is spoilt viciousness personified. Ther is fine work too from Ray Chenez’s Nireno who enjoys no arias (save one added later: “Qui perde un momento”) but shares “La giustizia” to an extent with Stoyanova; and actively ripostes Wallroth in many recitatives.

Tittoto is magnificent. Undercutting all low notes elsewhere he seems to uproot the floorboards on an otherwise bare stage. A fine actor, his dramatic death-speech “Dal Fulgor” comes as a pendant to his troubled betrayed sense in “Se a me non sei crudele” when he realizes he’s not getting his way. It’s a turbulent bass aria, almost nauseous in a bodily self-recognition.

The pull between the three principals is memorable too. Cornelia’s shuddering grief at the head of her husband isn’t flinched from, and “Son nata a lagrimar” almost banishes remembrance of Cesare’s famous aria “Va tacito”. Combined with Stoyanova, Taylor scorches an arc of pain and desperation that extend Act One to a different place altogether. One audience member complained of its length. One wonders why they just didn’t buy the CDs.

Mezzo Taylor’s reach is soprano and her range is incandescent, her high notes enriched by piercingly high coloratura. Beyond that, Taylor stamps huge dignity with Cornelia’s sorrow. She shows more of this when Stoyanova’s Sesto is being wrenched from her. Again there’s duetting and “Cessa omai” is a desolate wish for death. At such points, with McVicar’s direction – Taylor is literally hauled on a leash by Tittoto and attendants – it almost becomes her opera.

Naturally Cleopatra can’t allow that and Wallroth is both more mobile and, as expected, infinitely various. Wallroth’s soprano is both fresh and stratospheric, hitting dotted rhythms and excitement as you might expect. But there is also an affect, a pull to tragic depths where like Cornelia she contemplates suicide in “E pur cosi”, her plangent counterpart to Cornelia, if for less tragic reasons: she’s only just fallen in love, and her lover isn’t after all dead.

Elsewhere excitement and self-delight erupt in “Tu la mia stella sei” where Constable’s lighting does indeed stamp stars on the floor and Wallroth imitates the twitter of birds in more dotted rhythms. There’s a sexual frisson in ‘waking’ to seduce Cesare in “V’adoro, pupille”, confirmed love in the rapturous “Venere bella” where war and sexual desire mix. Even more consummated, the final duet with Cesare “Caro! Bella!” confirms an erotic impulse, almost, to match the entwined finale of Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea. If more public and a lot more decorous.

Nussbaum Cohen’s Cesare bestrides the stage in set pieces, most renowned being his aria “Va tacito”. The haunting horn obligato is performed standing (player not credited) as George’s choreography has protagonists march in a game of political chess. Cesare peers for a hunter’s vantage. It’s the most famous moment of the opera, strikingly original, Cesare continually alert, stalking the enemy. Cohen’s counter-tenor slips like a hunting-dog alongside the horn’s tang, two quietly striking through the dawn together. This allows Nussbaum Cohen to blossom in quiet steel.

Since earlier too there is a more shadowed side to Cesare’s voice through his meditation on mortality and the end of ambition in “Alma del gran Pompeo” at his rival’s funeral urn. Beyond the political, Nussbaum Cohen’s amorous “Se in fiorito” to Wallroth’s Cleopatra with sexy tenderness and urgent lust, is countered by north-star resolve later in “Al lampo dell’armi” and triumphant return: first in “Dall’ondoso periglio” and straight after “Aure deh per pieta” which blazons Nussbaum Cohen’s higher range: trumpets rather than hunting horns.

Some audience members’ comments might demur. “That singer with the girly voice” was one verdict on Nussbaum Cohen “Which one is Cleopatra among all those black-dress floozies?” Subliminally perhaps, McVicar has made his point.

The Orchestra of the Age of the Enlightenment plays with superlative colour, never afraid of expressive rough edges, though virtually undetectable. Terrific attack from Cummings at the keyboard is augmented by on-stage violinist Kati Debretzeni’s cadenzas on “Va tacito” whirling around Cleopatra like a haunting; William Cole on the second harpsichord, and continuos: Jonathan Manson’s expressively wrought cello, Christine Sticher’s sonorous bass entwined with the cello, William Carter’s memorably seductive theorbo, and Joy Smith’s riffling harp ushering Cleopatra’s bed.

Unlike 2005, this production might establish two Cleopatras as stars. Alder has arrived, Wallroth (she performed on 12th and 19th July) deserves to follow. Another revival awaits, with luck.