Erl Passion Play: Dana Rufolo

Dana Rufolo at the Passion Play in Austria

1 September 2019

The Passion Play in Erl, Austria, of this year [2019] is a theatrical event, and so it cannot escape being evaluated according to the norms of dramatic presentation. lt is also a community event that has affected neighbourly relations among the inhabitants of Erl over generations. lt is a religious dramatization in that the Passion of Christ is enacted on a secular stage. It is also a drama in that the Austrian playwright Felix Mitterer wrote the script.

Erl’s Passion Play embodies an ingenious social concept in that the participants are the townspeople of Erl, Tyrol. lt is staged in different versions and with different directors every six years. Multiple generations play on stage, and individuals play multiple roles throughout their lifetime. They begin by participating in the crowd scenes as babes or kindergarteners, then pass through youthful adulthood as the entourage of men and women around Jesus or eventually Jesus himself, and they terminate their community acting career as Jewish high priests or Roman military officers. Village community bonding through theatre is a brilliant idea and has become the overarching advantage to staging Passion Plays. The 85-member association of Passion Play organizers feature many, including the three-year-old association in Poole, UK, that started in recent decades, long after the original motivation for staging these plays — to thank the Christian god for having spared their town during a plague epidemic — has receded in importance.

Erl has been besmirched with its own #metoo story. In November 2018, the then-director of a separate entity in Erl, the Festspielhaus (specializing in music and opera) was accused of inappropriate dealings with the mostly Eastern European budding young female stars who were engaged by that house. When l asked if this scandal had affected ticket sales to the Passion Play, the press manager, Claudia Dresch, said that it is necessary to continually repeat that the two buildings are completely independent. The Passion Play is run by a “Verein”, a not-for-profit organization; the Festspielhaus is a commercial operation financed by large entrepreneurs. All the same, on the day of the premiere, 30,000 tickets had been sold out of 48,000 available.

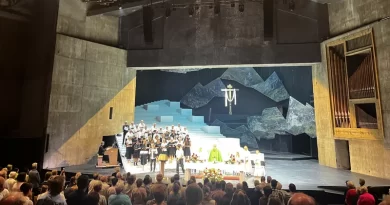

Script is by Felix Mitterer. 1,500 people can attend in raked auditorium.

Photo credit: Peter Kitzbichler.

The most famous Passion Play is in Germany, in the Bavarian town of Oberammergau. It is performed every ten years. l have reported on this German-language production in this publication previously and hope to continue to do so. But in reality, there are hundreds of villages and towns that produce Passion Plays. The commitment to producing Passion Plays at regular intervals in Erl and nearby comes under the organization of the Austrian network of the European Passion Play Association. Joining together permitted the exchange of costumes between neighbouring villages and reinforced the fact that by involving several generations in this event, the experience became a part of the village identity. The association encircles the two founding philosophical strands to Passion Play production as well, one being that evangelization helps to spread the word of God, and the other the belief that it gave youth an activity and a focus. This was especially true after World War Two when there were few resources and not much to do, the priests generally developed this youth activity within their parish churches.

ln Mitterer’s version of the play, the story of Jesus Christ’s condemnation by Pontius Pilate and the high priests, and his crucifixion, is told in 15 scenes beginning with his arrival in Jerusalem where he is met by hundreds of people and children waving palm fronds, through the scene of the Last Supper represented as a modern-day symbolic sharing of the body and blood of Christ, to the final scene of crucified Jesus being removed from the cross.

Mitterer injected modernist touches at random places in the traditional biblical narrative which deeply disturbed some audience members. Showing Jesus as a father is but one example. Some disciples are cast as women and some of his lines reveal sympathy with feminist arguments; the enactment of historically late church rituals such as reciting the Vater Unser (the Lord’s Prayer) is a further anachronism.

Above all, the most radical aspect to Mitterer’s version is the humanization of Jesus. He was visibly trembling, and his voice was shaky from fright, during the eighth scene, in the Garden of Gethsemane where he awaits sentencing. “lch kann nicht mehr” he says: “l can’t take this any longer”. He struggles with the weight of his cross when he is obliged to carry it. A physically weak, frightened Jesus unsure of the future is a new interpretation of his biblical character. Felix Mitterer has said, in German but translated here, “It has been the greatest challenge of my life as a dramatist to write a new version of the Passion Christi for Erl. My script is an unusual and unconventional look at Jesus and the men and women of his era. And of the enemies of Jesus.”

Garden of Gethsemane scene.

Photo credit: Peter Kitzbichler.

The strongest element of the set design was a mobile prop of two concentric circles — one just large enough to encircle Jesus alone during the Last Supper scene, and the second large enough to encircle his disciples and family members — except for the child, who stood just outside the second circle. The set consisted of the raked bare stage onto which the crowds gathered, and a rear stage of three levels extending nearly the stage length representing rock formations that permitted flowing processions of various groups including the crowd singing in the chorus. Costumes were beautiful, dominantly red and rust-hued. The stage flooring was embellished with translucent squares that served to guide the actors; Jesus was especially illuminated because he stood on one of them when he is sentenced to crucifixion.

As a theatrical event, the director Markus Plattner’s interpretation of Felix Mitterer’s script left something to be desired. Although touted as a performance space with superior acoustics, the stage hardly reflected the speeches of the cast into the back of the auditorium. l was seated towards the back of a steeply raked audience (it had an approximate 20 percent incline), but the stage was inversely raked (about 10 percent), so this ought not to have been a significant disadvantage. Generally, however, audience members complained during the entr’acte that they could not hear the delivered lines.

Lack of audibility was only one of the problems. Plattner did not direct the crowd scenes with any skill. He was inclined to keep the cast of 600 amateur actors (form a total of 1,450 village inhabitants) on stage in supine positions, which was more a management tactic than an inspired directorial decision. The scene where Jesus is crucified was unacceptable in that the crowd — men, women, and children — simply sunk to the stage floor and watched impassively, virtually indifferently, as their Lord was strung up to die.

Perhaps the most disturbing element of this Passion Play production was extra-dramatic — disturbing in that it contradicts and denies the spirit of Passion Plays. An out-of-town journalist told me he was charged fifty euros more per night for his hotel room in Erl than the advertised Internet price but was powerless to complain as specific prices had disappeared from the Internet page they’d been located on. Supposedly this was a special last-minute decision; in a Passion Play season prices increase. l can only presume this act was the consequence of an attempt to recuperate loss of clients due to the Festspielhaus scandal. It turns out that the family owners of that particular hotel are long-standing Passion Play actors, going back generations and representing just about every role — including that of Judas.