Dublin theatre round-up autumn 2019 part 2

Bill Grantham in Dublin and Galway

1 November 2019

I’ve long been an admirer of the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini’s work but always steered clear of his 1975 film Salò o le 120 Giornate di Sodoma, based on the novel Les 120 Journées de Sodome by the Marquis de Sade, because I’m rather squeamish. But when writer-director Dylan Tighe’s adaptation, Pasolino’s Salò Redubbed was announced at the Abbey Theatre’s Peacock Stage during the Dublin Theatre Festival — this is the second of two articles on that event with my first being here — I knew I had to see the film first. It was everything I feared – brutal, violent, relentless – but also rather brilliant, transposing Sade’s novel to Salò, the ancient lakeside town in northern Italy during the nineteen months of 1943-1945 when it was the seat of the short-lived, Nazi-controlled Italian Social Republic.

After World War Two, intellectuals such as Albert Camus and Raymond Queneau, in the long shadow of fascism, connected Sade not to the revolutionary spirit of liberty as his supporters asserted but to the death-world of totalitarianism. This connection is made by Pasolini in his film by setting it in the last throes of Mussolini’s awful regime. As Mitchell Abidor says of the original novel in a recent issue of The New York Review of Books, “Both the content and the worldview expressed in The 120 Days of Sodom make it as close to a repellently unreadable book as has ever been written.” The same could be said of Salò, except that in Pasolini’s hands, it’s repellently watchable.

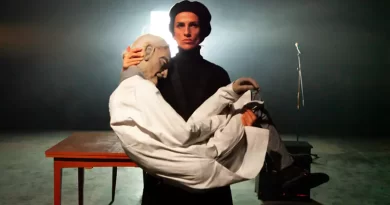

Pasolini’s Salò Redubbed. Photo credit Luca Truffarell.

This set a high bar for Dylan Tighe, who manages to surmount it effortlessly. The entire film is shown in back-projection during the performance (enough to send a small number of people out the exits, as usually happens). In the foreground, there’s a further transposition from fascist Italy to relatively recent Ireland, to the fate of adults and children in state and church-run bodies, where they are victims of Sade-like barbarity and neglect. The parallels with the Pasolini-Sade fiction, drawn from actual accounts of these places, are chilling, wherein the worst of fantasy is seen as actually existing in the embedded institutional actions of an ostensibly civilized country. The use of the Pasolini film as a frame liberates this story from the conventions of agitprop, making it in its theatricality more immediate and more real. A quite magnificent piece of theatre that sticks to you like a burr. Fine performances as perpetrators and victims from Thomas Collins, Peter Gaynor, Lauren Larkin, Niamh McCann, Gina Moxley, Will O’Connell and Daniel Reardon.

A more conventional type of engaged theatre, but in its own way richly rewarding, came in Prime Cut’s production of Fionnuala Kennedy’s Removed at the Axis Community Centre in Ballymun, a suburb of Dublin. I admit to having been in a bad mood when I arrived since the theatre is a one-hundred-kilometre drive from my home and I attended a school matinee starting at eleven in the morning. Fairly or unfairly, I’m also quite allergic to so-called “community theatre” which (for me) too often beats me over the head with its obviousness.

But all these prejudices were swiftly dispelled by this production. It tells the story of Adam, a boy in Northern Ireland who, alongside his younger brother, was plucked by the state social system from an alcoholic mother and placed in foster families and care homes. Adam, played with great delicacy by Conor J Maguire, reviews his life from the standpoint of a 19-year-old looking back with sadness and disappointment at years of indifference and neglect, albeit sometimes redeemed by sporadic acts of care and kindness. At the end of his institutionalized years, Adam reaches adulthood and is cast adrift with scant support and resources to fend for himself.

Removed was enriching, challenging, and moving. Emma Jordan directed well and the production was effectively designed by Ciaran Bagnall and lit by Paul Keogan.

More conventionally, the venerable Druid Theatre brought its latest production, Nancy Harris’ The Beacon, directed by Garry Hynes, to the Gate Theatre. I say “conventionally” since the play is determinedly old-fashioned, almost Chekhovian in its pacing and story-telling; it is also oddly timeless, as if it could have been written at any moment in the past 50 years.

Removed at the Axis Community Centre in Ballymun.

In a home full of secrets, Beiv (Jane Brennan), an artist living off the coast of Cork who paints large, evocative feminist canvases, is said to have murdered her husband ten years earlier. Her caustic son Colm (Marty Rea), who has come for a visit from San Francisco, reunites with his childhood friend and former lover Donal (lan Lloyd Anderson), causing complications with his new bride Bonnie (Rae Gray), an ingénue art student. Some commentators have criticized the play as being a painting-by-numbers expedition into familiar themes. There’s even a loud bang — not actually a gunshot — just before the interval. If you’re particularly high-minded, the critics are probably right. But l found it a pleasure seeing even the well-worn done well. The writing is good and the performances — particularly from Jane Brennan and the always-great Marty Rea — very fine, as is Garry Hynes’ smart direction and Francis O’Connor’s set and costume design. There’s much to enjoy here and nothing to endure.

Galway-based Moonfish Theatre previously staged a highly popular dramatized version of Joseph O’Connor’s novel Star of the Sea about passengers of the eponymous ship who set sail for America during the Irish potato famine in 1847. They have returned to the Abbey with a “freely adapted” version of its sequel, also based on an O’Connor novel, Redemption Fall. lt is set in the USA in the years following the Civil War. The production emphasizes music, melding traditional American tunes with Irish ballads and original pieces to create what it calls its “theatre-gig”. The work is created by the ensemble, so all of the performer-instrumentalists get a deserved shout-out: Ionia Ni Chróinín, Mairead Ni Chróinín, Morgan Cooke, Grace Kiely, Zita Monahan McGowan, Pat Hargan, and Seán T. Ó Meallaigh. While the musical numbers were well played and sung, and the adaptation of the novel was serviceable, l felt that the players were generally better musicians than actors; their lack of dramatic clarity wore down the pace. But I was still glad to see it.

Redemption Fall by Moonfish Theatre.

More musical theatre at the Abbey during the festival: the well-regarded writer Dermot Bolger’s Last Orders at the Dockside, sponsored by the Dublin Dock Company. lt traces the impact on communities of the slow decline of the city’s warehouses and wharves, now glibly called Silicon Docks to reflect the latest tenants: Facebook and Google. The play starts in 1980 and parallels the decline of the inner-city working-class world of the docklands with the tumultuous changes in Irish society since then. It’s a worthy subject and well performed by a cast that includes Brid Ni Neachtain, Lisa Lambe, Juliette Crosbie, and Terry O’Neill, mixing music and drama to tell its story.

l didn’t think it worked very well. A fair measure of the blame must fall on the shoulders of director Graham McLaren, who is also one of the joint-directors of the Abbey Theatre itself. There’s been a fair amount of criticism of McLaren and his co-director Neil Murray since their arrival from Scotland in 2016. There has always been criticism of Abbey chiefs, so part of this should be treated as the usual background noise associated with running a national theatre. But McLaren’s approach to Last Orders was stale, anachronistic, and dull. To me, it was reminiscent of shows from the 1970s but tired — lacking any kind of contemporary excitement or spark. Nobody should be judged on just one show, but this should have been one of the mainstays of the festival. Instead, it was just forgettable. Taken with a general policy drift and absence of clarity and focus, there are ominous signs that the McLaren-Murray regime is sinking into dullness, and that isn’t good enough for a theatre with the Abbey’s history and traditions.