Caryl Churchill in Italy today

Maggie Rose in Lombardy

26 February 2023

Caryl Churchill’s work is enjoying unprecedented success in Italy. After many decades when her work was rarely performed, over the last year there have been several significant productions: My Heart’s Desire (l’amore del cuore) directed by Lisa Ferlazzo Natoli at Milan’s Franco Parenti theatre, Top Girls by Monica Nappo Kelly at Parma’s Teatrodue, and Love and Information (l’amore e informazioni) directed by Marina Bianchi at Milan’s Elfo Puccini theatre. All these productions are directed and translated by women, who, with a few exceptions, have been responsible for Churchill’s growing recognition in Italy.

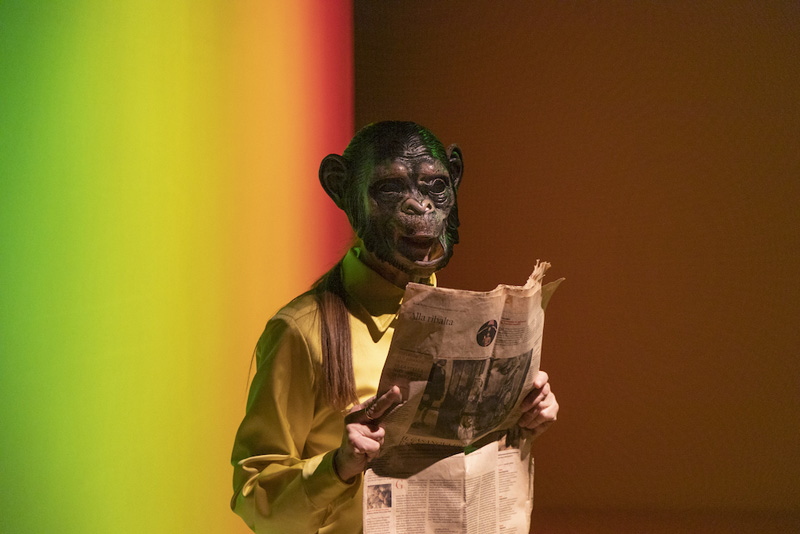

Love and Information. Photo credit: Laila Pozzo.

Love and Information, which made its debut at the Royal Court in 2012, finally had its debut in Italy in January 2023. Director Marina Bianchi is no newcomer to Churchill’s plays, having directed the premiere here of Top Girls in 1988.

Her fast-paced production sees three actors and a dancer rapidly switching roles and appearance as the 57 brief scenes flash on and off the stage. The action rolls out on a bare stage except for three chairs and a table, piled up with animal masks, wigs, etc.

Not only do the actors meet the challenge of performing at top speed, seamlessly moving from one scene to the next, but they also manage to swiftly re-arrange the table and chairs, according to the scene, and change their appearance in plain sight of the audience, donning a wig or a mask to assume their new character.

The absence of changes in scenery is substituted by headings in English and Italian, projected onto a large screen. Headings such as ‘Depression’, ‘Climate’, ‘Wife’ etc, act as visual cues to allow us to get the gist of each scene the moment it starts, while brief musical clips, from the Beatles to Amy Winehouse and David Bowie, conjure up a particular atmosphere. Love of all kinds is deftly mixed with information that deals with a variety of topics.

In the ‘Depression’ segment, we no sooner register the expression on the face of a woman who is visibly depressed – the stage picture recalls Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” – than the actors move into the next scene.

Love and Information.

Photo credit: Laila Pozzo.

These ever-changing situations and moods are tantamount to an overload of fragmented information, so creating a parody of the Internet and the social media platforms that operate on similar lines. Churchill, moreover, invites us to reflect on these phenomena with characteristic humour and playfulness. The scene, ‘Fan’, exploring the love two unnamed characters feel for an unnamed celebrity, shows them competing with each other to show they know more about him, a competition that touches on the absurd when the situation reaches stalemate; neither of them can remember what the star’s favourite smell is. Is it roses? Is it chicken? The scene finishes in total despondency, with the Beckettian line, “What are we going to do?”

The strength of the production lies in the way it succeeds in conveying the mix of tragedy and comedy that pervades Churchill’s theatre, leaving us exhilarated by the roller coaster journey the play has taken us on, but also concerned with the predicaments and existential angst of many of the characters who fleetingly come and go.

In November I caught Shakespeare’s The Tempest at Milan’s Piccolo Teatro, in a production by Alessandro Serra. It seems to me that more than many other plays in the Shakespeare canon, this tragi-comedy lies open to an infinite number of interpretations. In 1610 and 1611 when Shakespeare wrote it, he almost certainly had in mind the travels of his contemporaries who were venturing overseas to discover the treasures and pitfalls of the New World.

In 1609 there was a real-life tragedy when several Englishmen on a trip to Virginia lost their lives, inspiring Shakespeare to write his play, in which a shipwreck maroons Prospero, the exiled Duke of Milan, and his daughter Miranda on a far-flung island somewhere in the Mediterranean. In his director’s notes, Alessandro Serra leaves us in no doubt as to his interpretation of Shakespeare’s final work, “The Tempest is a hymn to the theatre deploying theatre itself, whose magical power resides in the unique and unrepeatable opportunity to reach a metaphysical realm, thanks to the antics of a company of players who tread the boards, with very few stage properties and a pile of patched costumes … human beings will always feel nostalgia for theatre since it is the only place left, where they can demand their right to have access to magic”

To achieve his goal, this multi-faceted practitioner takes almost total control of the production, directing, adapting and translating, as well as designing the set, lighting, sound and costumes, all of which highlight the elements of theatrical illusion, theatricality and magic that are likewise a leitmotif in Shakespeare’s tragicomedy. The opening scene (as one might expect) presents a stunning storm during which Ariel (Chiara Michelini) in a vibrant dance, manages to embody those natural elements so ferociously unleashed.

Serra, moreover, also ‘paints’ some magnificent stage pictures, with chiaroscuro effects reminiscent of Caravaggio. The episode, when Ariel, on Prospero’s orders, conjures up a banquet only to make it disappear before the Royals can eat anything, was among these. The Neapolitan servants, Trinculo and Stephano, were also well conceived; their Commedia dell’arte antics, proving hilarious. However, I was left feeling that the production does not chime as it could in our contemporary world.

Doesn’t Shakespeare explore a brutal clash between Western civilization and an island culture embodied in the conflict between Prospero, Duke of Milan and Caliban, the only native on the island? The fact that Caliban (Jared McNeill) comes over as being not too intelligent, while Prospero’s role is reduced (Serra’s adaptation lasts 90 minutes compared to the usual running time of over three hours) takes much of the power out of their struggle. Caliban, the crafty instigator of a scheme in which he involves Trinculo and Stefano to overthrow Prospero, likewise loses his sinister, revengeful side, overshadowed as it is by the sometimes camp comedy of the two Neapolitans. And last, aren’t Prospero and Miranda two displaced individuals, who suffer deeply from their exile far from Milan? The production it seems to me is beautifully honed, while lacking the stuff of tragedy.

My second show, Theatre Protons’s Winterreise took me to the Triennale theatre’s small studio space. As audience members entered the playing area, we were immediately confronted with an array of sleeping bags and blankets carefully arranged, while hospital-like, single beds were positioned at the back and on the left and right. Some spectators were invited to sit or lie on the beds, making us all feel part of the action.

To the rear, a large screen offered a poignant, silent account of male migrants on the move, in hostels and on the road. Sometimes the screen divided into small boxes, so we could observe in close-up the strikingly different faces of these men from countries around the world, including their tiniest facial movements and reactions as they attempt to cope with what is a traumatic experience.

Almost immediately a lone, middle-aged man, poorly dressed and weary, enters, making his way through the sleeping bags. Having taken a seat on one of the beds, he bursts into song, surprisingly delivering the first of Franz Schubert’s Lieders in German. For the 70 minutes’ running time, the man (Janos Szemenyel) carries out the everyday actions of a displaced person, living in dire poverty: he eats a meal from a can, shaves, using a toilet seat, gets undressed and dressed again, goes to bed.

At a certain point a policeman erupts into the room to check the man’s fingerprints, bizarrely obliging him to give his fingerprints repeated times. All this is accompanied by the man intermittently singing Schubert, accompanied by a pianist (Karoly Mocsari), while the film continues to chart the lives of so many men in a similar predicament to the migrant-singer. Director Kornel Mundruczò has had the truly brilliant idea to juxtapose one of the most famous musical works of the Romantic era, Schubert’s story of a lone traveler (1827), whose unrequited love for a young lady sends him, wandering through beautiful country scenery, with the terrible dilemma of migrants today who find themselves displaced and on the move, far from their loved ones in what is often the squalor of inhospitable cities.