“A Midsummer Night’s Dream” x3

Neil Dowden at A Midsummer Night’s Dream

(Bridge Theatre, Globe Theatre, Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre)

1 September 2019

This summer London has seen three major productions of Shakespeare’s fantastical romantic comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream, one indoors (at the Bridge Theatre) and two outdoors (at the Globe Theatre and Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre). Of course, it is one of the Bard’s most protean plays. With its mixture of erotic romance, knockabout humour, and magical trickery in which courtiers, mechanicals, and fairies collide, every production of the play is likely to be different as some elements are foregrounded over others. And indeed, the directors of these three shows take distinctively individual approaches, shedding new light (or darkness!) on this multifaceted work.

Artistic Director Nicholas Hytner’s outstanding A Midsummer Night’s Dream is in the same mould as his semi-promenade “immersive” production of Julius Caesar at the Bridge Theatre last year in which part of the audience is caught up in the action. Rather than forming the crowds addressed by Roman demagogues, this time promenaders mingle with confused lovers and mischievous fairies in a wood near Athens. The show has an intoxicating, sensual vibe where (in Bunny Christie’s design) platforms with beds pop up from below the stage in unpredictable places, and glamorously costumed aerialists on swings entwine seductively from above as glitter balls spin to disco music.

But though this feel-good show becomes an infectious celebration of love, it starts very grimly. In the opening court scene, Hippolyta, ‘Queen of the Amazons’, is enclosed in a glass cage, very much the captive of the Athenian Duke Theseus ahead of a forced marriage. And Egeus’s insistence — at pain of death — that his daughter Hermia marry the husband he has chosen, Demetrius, rather than the man she loves, Lysander, is presented in similarly brutal terms. This is all about aggressive male patriarchy not consensual love. With the men dressed in black suits the sombre ambience is more akin to a funeral than a wedding. However, the tacit look of sisterly support that Hippolyta and Hermia exchange signals some hope. And once the lovers escape from the rigidity of the court into the freedom of the wood the mood begins to lighten.

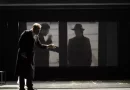

Nicholas Hytner’s version at The Bridge immerses the audience.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

The major innovation Hytner has made is not so much gender-swapping as role-changing in the fairy kingdom: Queen Titania speaks King Oberon’s lines, and Oberon speaks Titania’s, so that the traditional gender roles are reversed with the woman asserting her matriarchal potency and the punished man ending up with the ass-like Bottom in his bower. It’s an interesting idea of shaking up preconceptions about gender and sexuality in a show where the mixed-sex fairies and mechanicals do not conform to stereotypes, and where Lysander and Demetrius fancy each other as well as the girls although it does undermine the parallels between the court and fairy world. This wood is very much a gender-fluid, pansexual space where drugged-up fantasies run riot at night.

The anarchic spirit behind this mayhem is Puck in a brilliant, subversive performance from David Moorst, who contorts his body, dashes around all over the place, and ad-libs to the audience. Gwendoline Christie superbly plays his mistress Titania with magisterial authority and doubles as the fettered but feisty Hippolyta. Oliver Chris’s sternly overbearing Theseus contrasts with his unusually playful Oberon. Tessa Bonham Jones is a drolly pathetic Helena out of sync with the other lovers, especially when sparring with lsis Hainsworth’s angrily frustrated Hermia. And Hammed Animashaun is as lovably naive and enthusiastic Bottom wanting to play all the parts in the mechanicals’ comically inept performance of “Pyramus and Thisbe” for the forthcoming triple nuptial celebrations.

This has been chosen over even more direly amateurish entertainments which for once we briefly see, spot-lit accompanied by musical crescendo à la the television show Britain’s Got Talent, in a clever touch from Hytner that sums up this wonderfully inventive production.

Victoria Elliott and Sophie Russell at Shakespeare’s Globe.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Globe Theatre is also inventive but is, unfortunately, a far less rewarding experience. Associate artistic director Sean Holmes has previously directed an entertainingly irreverent, semi-improvised version of the play for London’s Filter Theatre (co-produced by Lyric Hammersmith, where he was the artistic director for almost ten years until leaving last autumn) which mirrored the inherent chaos of the story. But his new very different production is rather one-dimensional. He has sacrificed the layered richness of Shakespeare’s text in favour of full-throttle zany farce.

The strength of the show is the way in which performers engage with the audience — a trademark of Globe productions where the “groundlings” almost surround the actors who often walk through them to reach the stage. Indeed, this time there is on-stage audience participation: one man is brought on to play the minor mechanical Starveling (who has the role of Moonshine in “Pyramus and Thisbe”), eliciting much merriment at his genuine awkwardness — a real amateur upstaging the professionals pretending to be amateurish. lt’s a crowd-pleasing ploy that’s amusingly executed.

The trouble is it feels like Holmes is trying too hard in going for the comic jugular — it’s all a bit hyper. The inspiration for his carnivalesque approach seems to be the New Orleans Mardi Gras, with its psychedelic riot of colourful costumes (designer Jean Chan) and Dixieland-style jazz (composer Jim Fortune) played by the Hackney Colliery Band. The surreally humorous quality of this may fit in with the “love drug” part of the plot, but even the intimate scenes between the lovers are played coarsely for laughs with very little romance. Moreover, the whole show is, as it were, played out in bright light without any shade, so there is no sense of either supernatural mystery or threatening power from the court.

Although at the start, Victoria Elliott’s fierce Hippolyta has rope tied around her hands she quickly casts off the flimsy knot and proves to be more than a match for Peter Bourke’s elderly, feeble, and ludicrously overdressed Theseus. There seems to be very little sexual chemistry between her impetuously affectionate Titania and his coldly controlling Oberon. Jocelyn Jee Esien’s prima donna Bottom is a high-energy party-lover constantly appealing for the audience’s attention. The actors playing the four young lovers give rather shouty performances in a battle of the sexes that leaves little room for tenderness. And Puck is played by multiple cast members which pays comic dividends at the end when all of them vie for the honour of speaking the epilogue (as they knock each other out by blowing love darts) but it means the character lacks continuity or impact during the play.

Hammed Animashaun, Gwendoline Christie and Oliver Chris at the Bridge Theatre.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Dominic Hill’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre is much darker and wilder: less sunshine and more moonlight — a real slice of black magic. Although the opening court scene is staged as a posh celebration party, its tone is deliberately harsh and crude with vodka-swilling, posturing courtiers beatboxing and techno music blaring out. Beneath the elegant evening dress, naked power is at play. there is a repressive order of privilege which keeps people in their place. This is also true in the fairy kingdom where a similar patriarchal hierarchy is enforced — but in a more primitive way.

In fact, when the overs leave Athens and lose their way in the wood, they shed their inhibitions along with their city clothes as uncontrollable atavistic urges take over. At one point, Demetrius even threatens to rape Helena as she follows him. while Lysander starts to strangle Hermia to prove he now loves Helena. This is a scarily haunted place patrolled by sinister fairies perched on stilts and crutches — more like giant arachnids than gossamer beauties – who lurk behind bushes and communicate in sign language. Rachael Canning’s stunning design — which includes a giant illuminated ring containing Titania’s hammock so that she seems to be curled up in the moon — is otherworldly. And there is effective use of a creepy puppet for the changeling boy over whom Oberon and Titania fall out. Overall, the feeling is more nightmarish than dreamlike, like a Grimm fairy tale delving into the dark side of the psyche.

The rude mechanicals bring welcome comic relief with their innocent hopes and harmless squabbles while enjoying rehearsals in the wood — until of course terrified by Bottom unknowingly reappearing with ass’s ears and tail. Their eventual staging of “Pyramus and Thisbe” at court is winningly sincere if theatrically a disaster. But even at the end when partners are reconciled and lovers are united there is a sense of class division, with the courtiers sitting in the aisles by the audience and making cruelly patronizing comments on the performance.

Amber James is terrific as the disaffected trophy bride Hippolyta and the imperious, passionate Titania, while Kieran Hill is a laddishly nasty Theseus and vengefully jealous as Oberon. As Helena, Remy Beasley does a nice line in ironic pathos. Susan Wokoma’s Bottom is an engagingly committed thespian who fires up the others. Gareth Snook’s schoolmasterly Quince has to keep her over-keenness in check sometimes. And Myra McFadyen is a deliciously mischief-making Puck, at times perched like a ventriloquist’s dummy on the knee of her master Oberon — a nicely spooky image perfectly expressing this show’s take on manipulative power.