“In The Mirror”, National Theater of Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Dana Rufolo on a streamed Romanian theatre festival.

13 December 2021

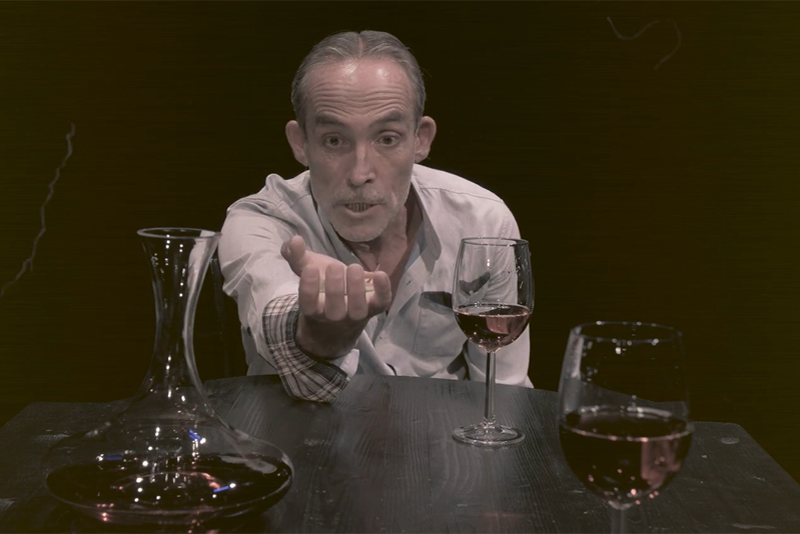

The National Theater of Cluj-Napoca, Romania’s streamed 2021 Theatre Festival offering În Oglindă (In The Mirror) is a response to the era of SARS-CoV-2 lockdowns. Experimental in nature, the sole actor – brilliant, masterfully controlled, and subtle Dan Chiorean – sustains a conversation with himself – except for, at the end of this 90-minute film, a succession of females each of whom appears briefly, silently, before leaving him alone all over again. Rather than in any way portraying suffering or psychological imbalance in the face of perpetual solitude, Chiorean’s character challenges the limits of solipsism, eventually thanking himself for the opportunity to have had such a frank exchange when he tells his other self at the opposite end of a long dark wooden table at which he sits for most of the action, “I never felt so free to tell you everything. We’ll see each other again.”

Still from the video-play In The Mirror with Dan Chiorean.

Film maker: Dragoş Popa.

The filmed In The Mirror, written by the Romanian playwright Radu F. Alexandru, is divided into “chapters”. In Chapter One, Chiorean, whose name is Matei, addresses a certain Emma who is supposedly sitting at the other end of the long wooden table. We see and hear only Matei and his replies; from him we learn that she is a pharmacist; that she seems to have been happy to see him when he had come into the pharmacy to have his prescriptions dispensed; that she accepted the invitation to visit him in his home and drink a coffee together. He repeats her comments, but since we never hear her speak we quickly understand that she isn’t there. Besides, he starts to envelope her in the prison of his intentions.

There are no overt sexual or relational desires, but rather he sets the rules of their interaction, beginning with his decision that each of them is to ask the other three questions. She confesses that when she was a child a distinguished older man kissed her hand; and he tells of how he’d saved a dog from the pound only to have to undergo extremely painful rabies shots when it died and his parents assumed the animal had been sick.

Still from the video-play In The Mirror with Alexandra Tarce and Dan Chiorean.

Film maker: Dragoş Popa.

The film maker Dragoş Popa does give Emma a ghostly presence for a few seconds, but chiefly it is Matei’s development as a character which is the dramatic objective of the piece. He is disappointed in Emma’s apparently casual interest in him and in Chapter Six he transforms into a bearded Securitate (the Romanian Stasi)-type personality who is aggressive to the other, invisible person – presumably Emma who is supposedly still seated at the other end of the table. His hitherto sensitive face has become a mask of strict harshness, and he offloads statements like “Shut up! … No tears on your face! … Victor is my name. … Confess your guilt! … Do you see how my blood freezes when you look at me? … You hurt my brother Matei”.

Perhaps this terrorizing scene is linked to the playwright’s Jewish identity; Judaism and World War Two are hinted at in Chapter Five when Matei tells Emma about pilgrims each leaving a commemorative stone at Franz Kafka’s grave in Prague. The reference, interpolated from the history of Romania in and after World War Two, reminds me once again of how the burden of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s dictatorship still traumatizes the middle-aged and elderly Romanian artists of today and how earnestly they undertake the task of reminding their youth of this inhumane and terrible past. It has always given a force and directness, a purpose, to Romanian theatre that catapults the message into a realm of intensity and feeling that one wishes more national theatres would emulate. In Chapter Six of In The Mirror, the Romanian word “frica” is frequently uttered, we even see it written: “fear”, though it is tempered by the word “sperenza” – hope.

Still from the video-play In The Mirror with Dan Chiorean.

Film maker: Dragoş Popa.

Chapter Seven is a return to former normalcy. Matei is a kindly clean-shaven person again. Emma supposedly asks him about Victor, but he denies all knowledge of that personage; all that happened is that “a shadow flew by.” Calvados is poured, there is music, they dance – the female shadow appearing and disappearing as he moves lithely. But the stakes are higher now – he talks about a psychiatrist he went to once who asked him three questions: are you lucky or unlucky; have you ever been in love; do you regret anything? Matei now confesses to feelings of helplessness (“impotenta”), and then in Chapter Nine he hears Emma tell him that she is not Emma. “But who are you?” he asks.

It is now that the long procession of women who smile at and respond warmly to Matei and seem to love or be friendly to him – one or two might even be mothers or mother figures – come on stage; they are physically real but shadow figures all the same.

As each woman walks away from the table and him, she removes a small symbolic object placed on the table and that that had been shown earlier in the piece – a small blue ball that looks pitted like the moon, for instance; or a tiny plastic dog when Matei described saving a dog; or a flat rectangular tile when he talked about a pile of stones left by pilgrims to Kafka’s grave, and one took away a ring he had earlier exhibited for a while and which had, like all the objects, reappeared on the table during this scene. This succession of women who Matei clearly loved and was crushed to have lost was a touching and melancholic final scene in the monologue. The wider political context, the fear, had melted into the story of a person’s solitude – accepted, tolerated, and even to an extent cherished but remembered as the way things are and not the way things had to be.

We never find out who Emma is really. But she does not appear to be a figment of Matei’s imagination. Rather, she appears to be a figment of his memory. One of Tennessee Williams’ characters says, “Have you ever noticed that life is all memory, except for the one present moment that goes by you so quick you hardly catch it going?”, and we are left with the feeling that our Matei has chosen a day in his days of prolonged loneliness to share memories with himself.

As I mentioned in my editorial for the Summer 2020 issue of the magazine Plays International & Europe, the video-play as it has been developed during the SARS-CoV-2 lockdowns is becoming an art form in itself. Neither a direct documentation of a theatre performance nor a filmed interpretation of a play, it can combine elements from both art forms to achieve a compelling visual and auditory experience for homebound audiences.

In The Mirror is an important landmark in the experimentation with formal possibilities. It would be impossible to have staged the play as it was filmed. The appearance and disappearance of objects from the table and the alteration in the actor’s physical appearance, including the addition of a bracelet when his character normalized after the paranoid Chapter Six, were effected by taking breaks in the filming process – Chiorean needed several days to grow a stubble, for instance (if he didn’t have to shave instead, which would mean the scenes were filmed out of dramatic sequence.) Additionally, Popa switched between shots in black and white and shots in colour, for no dramatically viable reason that I could see but this reveals an interest in the range of options available in modern film cameras.

No doubt, the script is flawed; the conceit of a person talking to himself – so skilfully achieved in Krapp’s Last Tape where Samuel Beckett focuses exclusively on the element of nostalgia – is obscured at times by not only the filmic technique of reducing human forms to chiaroscuro or producing multiple images of the same person, but also when, in Chapter Three, the director Andreea Iacob has Matei give a wide and sweeping gesture with his arm that suddenly includes us, the absent audience members. The problem of having untouched drinks on the table was also not satisfactorily resolved, even when the actor indicated surprise to see Emma’s glass still full.

We willingly suspended our disbelief, however, because from the start Matei’s relationship to place and time is fuzzy. He was definitely removed from other people, and we were vicariously happy as witnesses of his performance to note that isolation had turned him into a resilient philosopher rather than a stark raving madman.