Interview with David Lan, Young Vic Theatre

David Lan emigrated to London from South Africa in 1972 at the age of 20 after training as an actor and directing at South Africa’s first non-racial theatre, Athol Fugard’s The Space in Cape Town. He was already active as a playwright and has since written opera libretti and worked in film. Lan was a writer in residence at the Royal Court in the Nineties and has translated dramatists ranging from Chekhov to Euripides. He has been Artistic Director of the Young Vic since 2000.

Lan spoke to Jeremy Malies in the first week of the Young Vic’s production of I Am the Wind by Jon Fosse in a version by Simon Stephens directed by France’s preeminent theatrical polymath Patrice Chéreau.

20 April 2011

While appearing in a Brecht piece here Jane Horrocks described The Young Vic as “the most exciting place to work anywhere in the world”. You’d presumably agree. What puts a spring in your step as you walk through Waterloo to the theatre?

The real pleasure at the moment – and this is true of the shows that Jane has done here too – is that in I Am the Wind we are creating what I’m perfectly happy to call “high art”. In fact, it doesn’t get much higher. And yet when I watch the show, I realize that a large proportion of the audience is under 25 and from round the corner. They are at an early stage of their artistic experiences. I don’t know where else they go, but I don’t think they go to Covent Garden. They are enraptured by the power of what they see, and this also comes across in the reports from teachers who bring school kids here. We’ve had the world’s elite in terms of theatre directors visit us to see the opening nights of I Am the Wind and they are forming single unified audiences with the youngsters for a beautifully achieved piece of work.

ShotShop.

We managed something similar in The Good Soul of Szechwan with actors knowing that they were working at a very high level and having a close understanding with the audience as part of a direct process. In the bigger of our two studios, we currently have the company Only Connect who specialize in working with ex-offenders. The group has created a musical deriving mainly from the personal experiences of the cast. The piece has enormous vitality and it’s intensely moving to watch people who had been running their heads into the wall beginning to make something of themselves through art. Having this and Patrice Chéreau’s interpretation of I Am the Wind together is joyous.

The Good Soul of Szechuan.

Photo credit: Ralph Rapley – xmo4.com

You are on record as saying that you have been an admirer of Patrice Chéreau throughout your life. When did you first see his work and what was the effect?

I saw his production of Marivaux’s The Dispute at Villebon some 35 years ago. What I recognized was something that I didn’t know you could do and which gave me a dissatisfaction with many of the ways that people in Britain think about theatre. I’ve gradually begun to understand it as an attempt to talk about the world in a complex way – in terms of unfinished business and creating a sense of the reality of experience in direct but non-polemical terms. We have a tendency in this country to try and remove contradiction so that work is presented on the stage with a resolution, sometimes at quite a superficial level. Having reflected on this for most of my life, I think it probably derives from the fact that our theatre comes from the Restoration. It stems from a celebration of order – both political and social – with everybody in their right place.

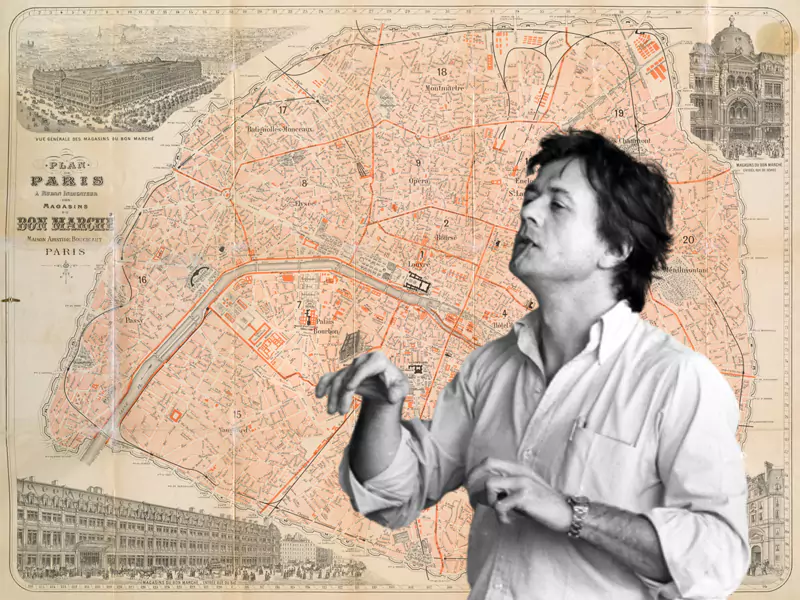

Patrice Chéreau.

There was something in Chéreau’s work that was deviant, anarchic, contradictory. I responded to that and a lot of my work – not so much as a writer or even a director but as a producer – has involved trying to keep the contradictions absolutely clear. There’s no consistent style. The only thing that’s consistent is that I try to work with the best people I can. This often means the best people on the planet. There is a very different attitude to ambitious artistic undertakings in Europe which is in some ways wonderful and in others problematic. But as long as you’re working, you work with contradiction. One only finds perfection in death.

Like the RSC and the Almeida, the Young Vic has had a period in exile for redevelopment. You now have two studio theatres to complement the main house. What were the challenges and rewards of the refurbishments?

A reward has been that having three spaces means we can now produce in different ways. Next week in the larger of our two studios [The Maria] we open with Kafka’s Monkey [an adaptation of Report to an Academy]. It’s a solo performance by Kathryn Hunter. If we did this in the main house, we could sell out easily but it’s an intimate piece and will work better in a small space. There’s a particular pleasure to be had from watching delicate, sensitive drama really close-up.

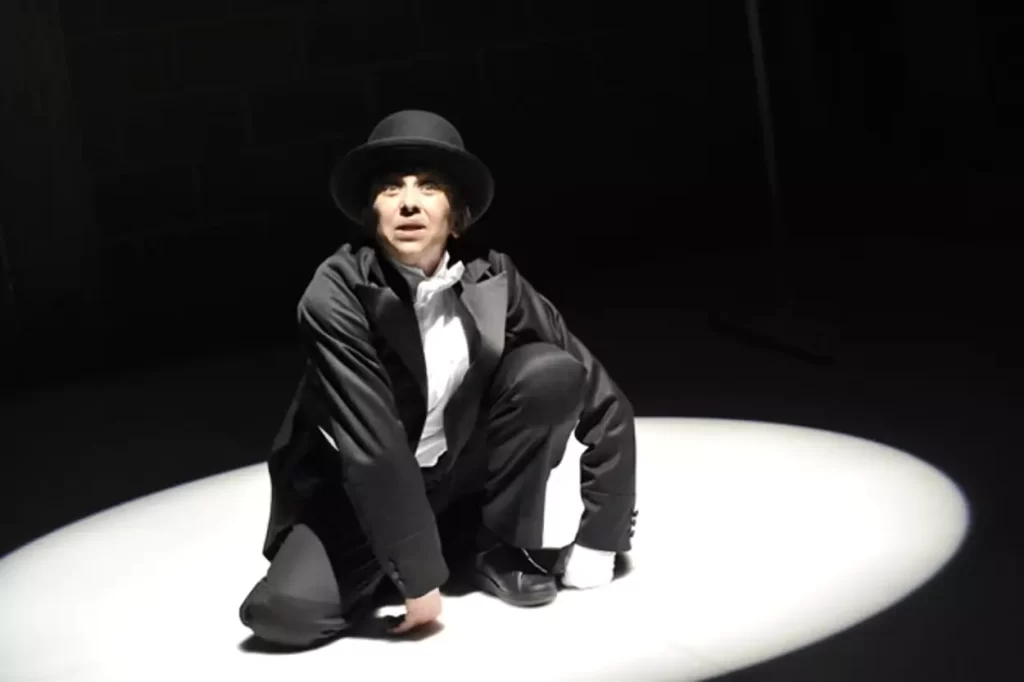

Kathryn Hunter in Kafka’s Monkey.

We run a big young directors programme and see ourselves as complementing the Royal Court’s initiatives with young writers. Having these two studios gives us the opportunity to produce things by relatively inexperienced people in a well-resourced way. The programme for directors is complex and provides young people with a chance to learn and be part of a producing theatre. The different performing spaces help with the work we do in our neighbourhood with schools, colleges, literacy programmes and people recovering from mental health problems. We also cooperate extensively with theatres in other countries, the links being as far afield as Rio de Janeiro, Iceland and Palestine.

Your programme for 2011 includes “Hamlet” starring Michael Sheen. As we sit here Michael has just finished a Passion play in his native Wales. Hamlet will be directed by Ian Rickson whose production of Jez Butterworth’s “Jerusalem” is currently playing in New York and tipped for a Tony Award. There’s much expectation. It’s early days but what can you tell us? Have you begun to consider how your “Hamlet” will look?

I think what you’re trying to say is that the stakes are high! Well, the show happened because Ian Rickson, who is an old friend even from before his Royal Court days, came to see me and announced that he’d like to do Hamlet with Michael. You don’t have to think about that too long! It’s being designed by Jeremy Herbert who did The Glass Menagerie for us. Jeremy is working with Ian at the moment on Pinter’s Betrayal which opens at the Comedy Theatre shortly. Alright – what can I can tell you about the production at this early stage? Well, it won’t be in doublet and hose!

The Young Vic’s production of “Kursk” by Bryony Lavery left me and other audience members with the sensation that we really had spent the evening in a submarine. Are there any secrets to the processes by which you transform the performance spaces here?

We encourage directors and designers to come into our theatres and imagine that nobody has ever done a show there before. The first question is, “Where shall we put the stage?” My preference is that every show should be done with the stage in a different part of the room because it’s the most powerful way I know to stimulate the imagination of the designer. It’s good to start with no assumptions. We pretty much rebuild the theatre every time.

iStock.

There has been a profusion of new theatres springing up in the Lambeth area recently. Are you in any sense a “neighbourhood” theatre? Do local people come here to make a gesture by staying on their home turf and at the same time breathing a sigh of relief that they are not seeing another West End musical? What has your demographic research revealed about audience profiles?

The marketing team has a good idea of who comes here and how often they come back. What has been established over the last few years is that people tend to go to the theatre nearest to where they live. There aren’t a great number of people living in Hammersmith who will go to Hampstead. And there are even fewer people living in Hammersmith who will go to, say, the Hackney Empire. London is surviving as a set of traditional villages within the metropolis.

iStock.

Much effort goes into getting the audiences we want. What matters to me is that moment when audience and show come together. The more complex the show the better but the more complex the audience the better. Whatever contradictions there are in the human experience, we try to reflect them in our audiences. We rebuilt the theatre to feel that the venue is open. There is absolutely nothing to keep anybody out. It’s very cheap and ten percent of our seats are free to people in our two boroughs – Lambeth and Southwark. It’s a democratic building and organisation in that we try to produce in a way that any citizen can engage with.

The Young Vic needs to generate about a third of its income every year through the box office or it can’t go on. But we have a full-time member of staff whose remit is to ensure that any place where people gather in this area might result in a free ticket reaching the right hands, and that person possibly coming away from here reflecting, “I just didn’t know that theatre was a possible way of thinking about me and the way I live.” We make this offer to them without any risk on their part.