“Krapp’s Last Tape” at the Barbican

Neil Dowden in Central London

2 May 2025

Samuel Beckett’s 1958 one-act play Krapp’s Last Tape seems to be on a loop. Starting soon after Gary Oldman’s show at York Theatre Royal comes Vicky Featherstone’s production starring Stephen Rea at the Barbican (first seen in Dublin last year). It may be a monodrama but it’s a two-hander – of a sort. The titular character has been briefly summing up each year of his life by making a tape recording on his birthday, and here as a 69-year-old he interacts with his younger self by listening to a tape he recorded 30 years earlier, which in turn is a reaction to one he made 10 years before that. As the title suggests, as he approaches three score and ten this is his final testament to a life that has dwindled into nothingness.

In case he had the opportunity, Rea presciently recorded the tape of the younger Krapp over a decade ago. This tape is used in the production and although Rea was then actually close to the age of the older Krapp, the timbre of his voice does sound sufficiently different from now so that it has the required effect of showing the character ageing. (This is not quite as remarkable as Samuel West who did the same but at age 39 in advance of his intention of playing the role as a 69-year-old in 2036!)

This is 45 minutes of extraordinarily concise and precise writing that encompasses almost the whole of one person’s existence, rewinding through old age, middle age, and youth. Krapp’s life does not so much flash before his eyes as echo in his ears. Beckett explores memory, loss, loneliness, and disappointment. There is a strong sense of waste. Krapp has failed as a writer and in his relationships – we hear how he left his girlfriend to focus more on his work but he never realized his potential. He has moved from romantic idealism to self-centred ambition and now existential despair with “nothing to say”. The fire has burnt out leaving only embers as he awaits death.

Krapp’s Last Tape is undeniably sombre – even by Beckett’s standards – but as always with this writer there is much compassion and also dark humour in his depiction of the human condition. There is even a bit of music-hall-style comic business with Krapp almost tripping over the skin of a banana he has just eaten, then making sure he throws the skin of his next banana off stage. Krapp himself seems to see life as a sardonic cosmic joke rather than a tragedy, though we see the pathos of a man who has retreated into introspective nihilism.

Since Beckett first wrote the play for the great Irish actor Patrick Magee, this challenging role has been tackled by the likes of Cyril Cusack, Albert Finney, John Hurt, Harold Pinter, and Michael Gambon. Now 78, Rea has had a notable stage as well as screen career, especially in Irish drama, including in the Eighties performances for Field Day Theatre Company which he co-founded with Brian Friel. This is the first time he has performed Beckett since playing Klov in Endgame at the Royal Court in the Seventies (when the author himself attended rehearsals). He brings to the role his own distinctive kind of lugubrious drollness, ideal for a character who appreciates the irony of how far short his hopes of life have been fulfilled.

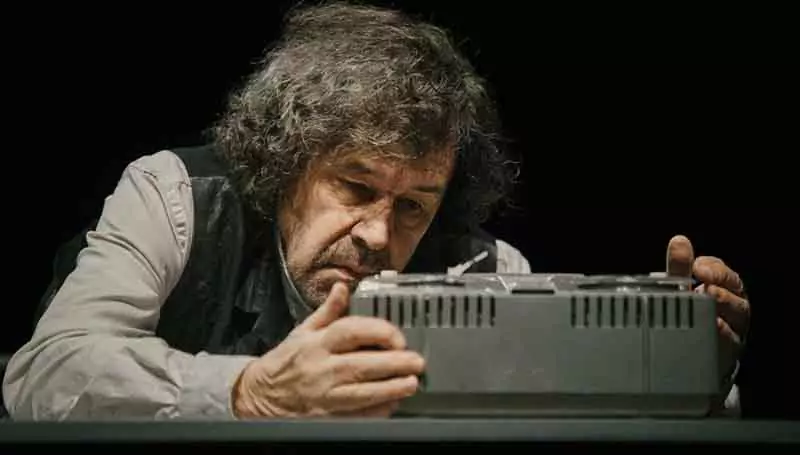

Rea gives a subtle, rather muted performance, speaking slowly in subdued tones on stage (though the recordings of his voice are noticeably crisper – audio director Stephen Wright), as if used to muttering to himself after many years of being alone. The overall mood is one of melancholic resignation rather than passionate anguish. The only time he displays a real sense of anger is when he abruptly pushes off the table the spools of tape he uses for his reel-to-reel recorder. Otherwise – apart from slowly jogging off stage to get his equipment – he remains largely motionless as he plays back the tape, occasionally pausing to take in what he has said (looking up the word “viduity” in a comically bulky dictionary) or fast-forwarding when he is bored. And when he uses a microphone to make his new recording he struggles to find anything worth uttering.

It’s a skilful and convincing account of the role, though not especially poignant. This intimate play would have more emotional impact if staged in a smaller theatre. Nonetheless, Featherstone’s production is quietly compelling. She has previously directed Rea in David Ireland’s Cyprus Avenue in the Abbey Theatre/Royal Theatre co-production in 2016 – Rea’s last time on the London stage. Jamie Vartan’s stripped-back design matches the play’s austere ambience, plus the addition of a shadowy outer fringe evoking the unknown future. There is a sliding doorway through which dim light sometimes shines on Krapp (lighting designer Paul Keogan), while the suspended lamp above him remains unilluminated, with the show gradually fading into pitch darkness.