“London Tide” at National Theatre, Lyttelton

Jeremy Malies on the South Bank

23 April 2024

“This is the story of a river / That springs from the mudbanks.” It is of course easy to point out one naff couplet over an evening; you could do it for anybody from Stephen Sondheim to Cole Porter. But it was the lyrics in this adaptation of Charles Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend by Ben Power that sat uneasily with me. The novel is presented as a play with music by Power who is jointly responsible for the lyrics with singer-songwriter PJ Harvey. Her sombre funereal music (she is known for wanting to make the listener feel uncomfortable) struck me as having a mission to avoid even a whiff of Dickens’s trademark sentimentality to the extent that the project became rootless.

Brandon Grace and Jake Wood.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

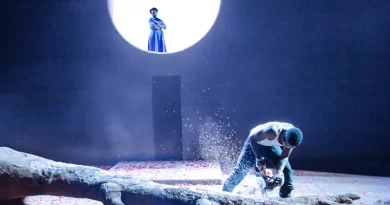

Presentation style by director Ian Rickson is physical theatre, and much of it works with simple stagecraft such as drowning characters fighting while encased in a plastic sheet, chairs and tables being picked up to serve as other objects in the backdrop, and what would usually be the apron of the stage seeing characters thrown into the water or rescued from it. The uncluttered set by Bunny Christie (there are few props, and flat surfaces have different purposes across the scenes) suggests that the Thames is always swirling in front of us across the Lyttelton’s unusually wide space. Christie has also designed costumes which are generally plain serge in grey or black to match the monochrome palette.

There is much to like about the dialogue delivery with not a hint of Estuary English or mannered cockney. Dialect coach Simon Money has helped the cast through the intricate exposition. But it’s the exposition that is a core problem with Power’s approach. Using a similar method to his version of The Lehman Trilogy¸ he bombards us with self-contained brief episodes framed with narration by other characters. Dickens wrote three plays before realizing where his core talent lay. I should not ventriloquize him, but he would surely have agreed that extended commentary is the enemy of drama which requires a broader sweep, sub-text, and dramatic irony from within the lines themselves.

The commentary (nearly every character gets a go) is full of shmaltzy descriptions of sunsets and sunrises. But Rickson and lighting designer Jack Knowles are too cute to show these to us. Knowles’s design is outstanding; it uses five banks of spot lamps which rise and fall, perhaps to show river fog, lamps carried by the waterside workers, or even the thinking of the characters becoming clouded by events. We see a political dinner in which Knowles reduces the ghastly upper-class fundraisers to silhouettes so underlining their facelessness. This is simple but effective and one of Power’s lines in the scene finds its mark as we think of our own politicians. “He knows nothing of government or the people he’s hoping to represent.”

A play with music is hardly a new genre but it’s in vogue with Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country and Cold War as well as Brokeback Mountain by Ashley Robinson. One of my problems with London Tide is that the dialogue rarely propels characters into the songs, all of which strive for gravitas with barely any humour. PJ Harvey should be respected for reinventing herself regularly but even in this genre, I became tired of the angst-ridden confrontational style.

Scott Karim. (Lighting by Jack Knowles.)

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

The campaigning or social conscience content of the dialogue is stronger than that of the lyrics and there are some sparks of humour in the spoken exchanges. “Schooling! It’s unnatural – as if the river ain’t enough …” says Jake Wood as Gaffer Hexham. And the feminist content finds its mark, with the luminous Bella Maclean as Bella Wilfer bemoaning her fate of being treated like a chattel in probate: “… left to him [John Harman] in a will like a dozen silver spoons.”

Setting? Even this refuses to be tied down. Power has heroine Lizzie Hexham (Ami Tredrea) tell us early on, “As to the exact year, there’s no need to be precise.” Soon after, her brother Charley (Brandon Grace) tells us how many of the characters can recall “watching the explosions as they built the Great Embankment” which would anchor the action in the 1840s. Later, we have contemporary clichés such as “I misspoke” and “I’m so proud of you”. I understand that these bland phrases are being deflated but it all struck me as being inconsequential. It would be better if Power and Rickson could go the whole way as with Underdog: The Other Other Brontë around the corner at the Dorfman which is an unabashed period goulash.

Movement direction by Anna Morrissey is inventive, most notably in a dream sequence when Lizzie dances with her two admirers, lawyer Eugene Wrayburn (Jamael Westman) and psychotic schoolmaster Bradley Headstone (Scott Karim). Karim impresses with the compulsive talking and social clumsiness of a charmless by-rote schoolteacher whose moral compass is overturned by lust for Lizzie. Karim shows the physical effects of this wonderfully.

Across a massive cast there are of course many other standouts. Bella Maclean is affecting and strong technically when showing the Pygmalion quandary she is in: “I’m caught between two worlds, and I don’t belong to either!” Making her professional stage debut, Ellie-May Sheridan as dolls’ dressmaker Jenny Wren is in familiar Dickensian territory having starred in the 2022 television series Dodger. Knowing she will always be on the shelf, she is sarcastic when seeing romance blossom for those around her: “Ah! The romantic lead!” Sheridan’s technique allows her to stress the ethereal quality of her character as written by Dickens.

There is no doubling-up in this cast of 21. The play is fitfully moving, notably in its discussion of social mobility, and much of the acting is first-rate. But the theme that women expect violence both from and between men deserves better handling. I had problems connecting with music and lyrics and am puzzled that the National has made such an investment in a clunky piece of writing and composing.