“Richard II” at Théatre Nanterre-Amandiers

Yann Messager reports from Nanterre

10 December 2023

Christophe Rauck’s Richard II is a captivating version. It has gripping and brilliantly played moments but also, sadly, suffers from a stylistic overconfidence that ultimately fails to wrap up the scope of the Shakespearean history in a convincing manner. The first half acquires narrative rhythm as well as dramatic breadth before beginning to creak in the second under the increasingly apparent failings of the artistic and acting direction of the play. There is a lack of cohesiveness between the varying eccentricities of certain characters’ interpretations. Similarly, there is a failure in achieving harmony between the more frivolous elements and the seriousness of the themes across the major scenes. The monotonous extremity chosen by Micha Lescot’s Richard contributes to a feeling at the end of the play that we have ordered chocolate but gotten strawberry instead.

Photo credit: Géraldine Aresteanu.

There is certainly a lot occurring stylistically here. The first scenes of Act I are played behind a see-through curtain with a bright beam of white light illuminating the speakers during their lines before they vanish again into black. Viewed through the curtain, this has the effect of surrounding the actors with a white gleaming halo. This is no doubt a crafty technical ruse that creates a mythological grace leading up to Bolingbroke’s banishment, a Garden of Eden quality as faces and details of raiment and physique are partially blurred by the curtain.

In this way, the audience is left with the impression of viewing exquisitely drawn animations as John of Gaunt (Thierry Bosc who also plays the Duke of York) paternally accompanies the discredited Henry Bolingbroke into his six-year banishment in a manner designed to give comfort and support. Bosc (as Gaunt) deserves praise and respect here. We are captivated by this grimacing, slouching elder statesman who with rigidity of movement, endearingly tells a pretender to the throne that being a beggar is nothing else but being free. He creates this with prophetically all-seeing eyes, peering at the sky, his diction riding along the waves of the translated text’s discussion of nature and the wanderings we suppose that Bolingbroke endures during the years of exile.

Photo credit: Géraldine Aresteanu.

But much more should be said about Bosc. Shortly before Gaunt’s death in Act II, there is the altercation at court between him and Richard. One cannot but be charmed by the masterfully controlled features of the old man in his wheelchair, being spun around by the young, narcissistic king. His disease-ridden irritable character is conveyed with great skill and imagination. It is truly powerful that this wronged senior member of the royal family should stand up in rage from the vehicle of his infirmity. What is more, Bosc manages this with slumped shoulders and an intentionality in his raised arm, pointed fingers and bronzed weather beaten face. He alone convinces us that before us is the king of England and that despite the frailty which dooms him, he is not yet bedridden to the point of bowing down before abuse of power. And in this way, the most Shakespearean of themes, the artifice and illusion that go into the achieving of power but also an accompanying Weberian violence are embodied (even if for brief moments) by this outstanding performer.

An actor’s objective in Richard II must surely be to convey the idea of the process by which political power is gauged. More than in some of the overtly political tragedies, power should be thought of here as a preeminent concept that courses through a drama of this kind. But I am hardly advocating anything new here. In this sense, Shakespearean histories could be said to (perhaps in a coarse manner) prophesy dialectical materialism but with the visionary foresight to stop short of reducing characters to quantified R or Stata intersectional predictions. The actor must always respond to as well as exude the map of power that is the stage. And as Albert Cohen might say, the handiest way to approximate power is to determine who kills or who can kill. All the emotions “secondary” to this fact are then mere reactions to it. Admiration, infatuation, friendship. For Shakespeare’s thoughts on friendship and power, we look to Hamlet:

The great man down, you mark his favorite flies.

The poor advanced makes friends of enemies.

And hitherto doth love on fortune tend,

For who not needs shall never lack a friend,

And who in want a hollow friend doth try

Directly seasons him his enemy.

To quote Frank Underwood from House of Cards: “Everything is about sex. Except sex. Sex is about power.” No matter the stylistic decisions, the flourishes of certain characters, in a play such as Richard II, a sensual experience of power must be projected and perceived by all. It should be made so tangible that the audience member feels it pushing at the characters in the way that marionettes are pulled around on their strings. This must be understood not merely at a conceptual and vaguely directorial level but in physical terms.

This is my main issue with the great Micha Lescot. I do realize that I risk offending his many ardent admirers who from the Avignon Festival last year to the doors of the Théâtre Nanterre-Amandiers last week, endlessly (and no doubt justifiably) relish the sensuality and projected frailty of his performances. But that is just my point. It would seem that Lescot is inebriated with his Joaquin Phoenix in Gladiator, an eerily feminine and feverishly weak regent.

Photo credit: Géraldine Aresteanu.

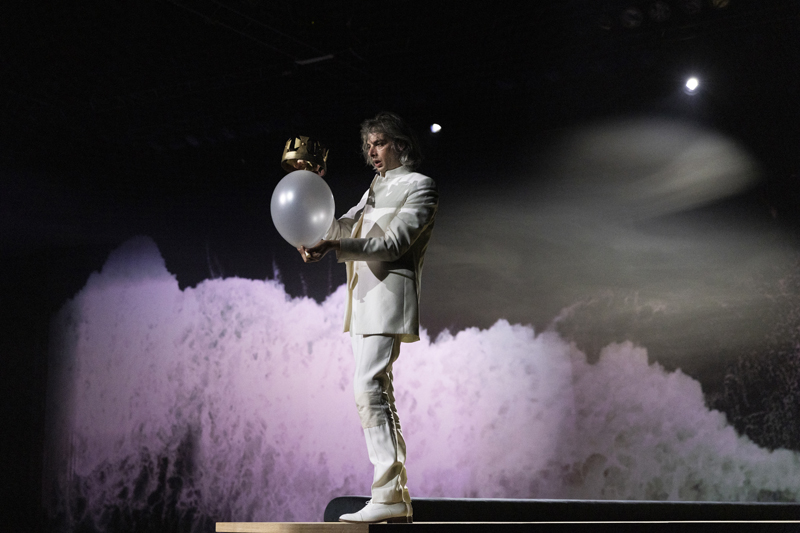

There is no question whether a regent of this type can work dramatically. But this then inevitably bears the great risk of floating away from the core of the play in a flight of whimsy. And indeed, in his white tuxedo, white leather shoes and shoulder-length silvery hair, dancing around on his heels in elongated poses, he seems at times more of a 1980s mafioso disco regular than a deranged, impish, puerile king of England.

One of the immediate consequences is that his voice never changes. Yes, the audience members look on with awe and amazement as he prances around the court and his courtiers, runs up the craggy beaches of Ireland and saunters along mountain peaks, airily reciting some of the greatest monologues in literature. The issue is whether this can be overdone and whether it is indeed overdone here. Any loss of subtlety can ruin the whole effect.

What I am saying (in more basic terms) is that Lescot’s Richard is so pompous at times that we forget he is human. He seems to us a god. And that is quite a trick to pull off. But we have not come to see a Prometheus figure getting chained to a rock by Zeus. But rather, to see a King Midas shine in a divine golden aura before becoming mere rock for eternity, a Pompeii, ashen cast of a man. His monotonous voice, to his great credit, takes a full two hours before it becomes truly tiresome. His wit is ingenious and there are incendiary flashes of a swooning spirit trapped amid castle towers. But as we trudge on, his high-pitched and detached questioning becomes just that. The greatest manifestation of this is perhaps his last monologue which he recites lying down with no inflection in the voice, just a high-pitched, childish babbling that all of us have heard and resented from a child relative.

This tragic fall from such a great actor then seems to us as horrifying as the fate of Richard II himself. Where is the Richard who cuts through the courtly pomp for fleeting moments and looks is in the eye? There are moments when the character should be implying: “I am one of you and I am wretchedly miserable.” Can Lescot’s Richard be said to have treated the Hollow Crown monologue fully? It seems not, for no change can be distinguished in him; there is no roaring ascent preceding the moment. During the monologue, he blows a balloon, places it in his crown as a head and then pierces it. The balloon majestically and pathetically twists around before flappingly (or rather flatulently), coming to rest in the middle of the stage. This piece of artistry truly lands its intended artistic punch. But when Lescot comes down from the seats of the courtroom and recites some of the most shudder-inducing words in the English language (which happen to be in French this time around):

Cover your heads and mock not flesh and blood

With solemn reverence: throw away respect,

Tradition, form and ceremonious duty,

For you have but mistook me all this while:

I live with bread like you, feel want,

Taste grief, need friends […]

I halt before the gripping line. When Lescot falls to the ground, he rushes through this. It is scarcely heard. In fact, I had the impression that we were receiving more from the balloon segment than from his speech here.

How desperately one wants to believe in this monologue. How feverishly we cling to every word, hoping it will be the visionary gleam that we know we will experience only a handful of times even in a life of regular theatre-going. We want to meet Lescot half-way. But that is not the job at hand here. With vivid memories of our own personal favourite interpretations of Richard, we often let these greater-than-life memories assuage our scathing critique of the present though ultimately with ill-fitting pardon. I feel that I could be seen as sullen (ungrateful?) in writing these worthless words about such a skilled and masterful player. But I do so perhaps in the hope of one day assisting the repressed (or dare I say irrepressible) triumph?

The first half of the play does indeed succeed in igniting the roaring ascent to fratricidal war across the British Isles. The set at the beginning consists of two large sets of seating (rather like the bleachers at a baseball match) which face each other on both sides of the stage with a computer-generated House of Commons figurehead projected on the back wall. It does give a powerful allure to the stage but one would hope that more attention could be brought to what at times can feel like a soulless desktop 3D rendering. However, this is more than compensated for by the entrancing visual effects which follow in the rest of the piece. These include terrifying waves breaking across the screen to wondrous effect as Richard sulks around the battlefield of his eventual demise and the more abstract and pastoral art of the garden scene.

Éric Challier’s Bolingbroke cannot fail to give a strong portrayal of the great political opponent whose vigour justifies this brawl which approaches a duration of three hours. With his mountainous physique and tressed long hair, Challier doesn’t need to do much to convince us of his willingness to take up arms. The stillness and rugged nobility of his features give the battle and general quarrelling scenes the tension that they deserve.

But similarly to Richard, we have a difficult time reading our Henry Bolingbroke. Does he feel any guilt at playing such a petty game as waging war to take power from his cousin? Or does he wake up in the morning with a profound conviction (and a lot of self-denial) that somehow there indeed is a God-inspired justification for political violence. We can’t really tell. He is wronged, yes, terribly so. But in the scenes showing Richard’s fall from grace, Challier’s Bolingbroke seems more to be averting his gaze from something grisly such as a dislocated shoulder being yanked back in place. Were this played in a more affirmative manner, perhaps it could have made for an interesting character study. But it doesn’t suit the broad-shouldered, grounded and steady political contender we come to know. Despite his evident robust support given to the overall play, at times it seems that he plays the text too literally. There is not enough doubt and insufficient attempts at self-justification in his scenes with Richard. We see too much sincere wincing at the fate of his dear cousin. This is perhaps where we lose him. The beautiful deftness with which he morosely seizes the crown has its impact reduced. We realize that we do not know who he has been throughout this journey. We begin to understand that we have not truly grasped his motivation and, more importantly, which of the infinite imbecilic but murderous ways in which he has chosen to persuade himself of the righteousness of his ambition. There is a certain two-dimensionality here of which we should be suspicious despite the striking natural qualities portending to grand spectacle.

The problems just discussed are compounded by the bizarre array of liberties taken with certain minor characters as well as some of the minor scenes. To pull off Shakespeare, one must be able to pass astutely from humour to a terrifying thrill within seconds rather in the manner of Hitchcock’s best films. There are many ways in which you can fail to achieve this. The easiest occurrence is a situation in which we are seriously and silently contemplating melodramatic acting that is meant to be funny, or the contrary, we are laughing when we are supposed to be crying. I doubt if I will ever forget a 2016 Othello at the Shakespeare Theater in Washington D.C. where Farah Tahir as the title character had rows of spectators howling in laughter with his yelps during Desdemona’s strangling.

Now this is quite an extreme example, but tragic acting is a thing of such subtlety with so many difficulties besetting its successful execution that we are never far from such a domain. The specific issue here is that the decision was made to play some of the less crucial dramatic scenes with an element of flippancy. A notable example is the imploring of King Henry by the Duchess of York to spare her conspiring child, Aumerle. Whether the flippancy that I saw in (contend was in) the scene was deliberate, I am truly at a loss to know. The five or so minutes within which we see Aumerle and the Duchess castrated before Bolingbroke seem so exaggerated and burlesque that the effect seems to have been intentional. The truly brilliant comedic chemistry between the Duke (Bosc) and Duchess of York (Murielle Colvez) leading up to the scene further strengthens the claim. Their bickering is truly hilarious and brilliantly done.

But one cannot help but feel a profound critical shudder at the incongruity of the stylistic decision with regards to the mounting urgency at this moment of the text. We are here after all in Act V, scene iii. Surely this is not the moment to be going on such stylistic adventures? Or if it is, then this attempt cannot be said to be the way to go about it. The stratagem drastically deflates the tension of the piece in an unsuccessful and awkward way by confronting a serious and goal-driven Bolingbroke with what seem like farcical stakes. The comedy here clearly overstays its welcome. I feel inclined to say that successful comedy in the final acts of Shakespearean tragedies is usually the product of the fool or his immediate peers. It then becomes fickle and has great underlying sadness or truth. Such plays get to a point where you must very carefully tread the line of comedic relief.

The same can be said of Emmanuel Noblet’s Aumerle when his parents learn that he is part of the conspiracy to overthrow the newly instated king. Noblet stares at the audience, his image expanded by a live film projection, trembling and wide-eyed for several minutes. One would feel tempted to laugh, only it goes on for so long we start wondering whether we are meant to take the acting seriously. In this case, my intuition is that we are. I do, however, want to celebrate Murielle Colvez’s Duchess of York. If merriment is to be had from these comedic scenes, Colvez does reveal an impressive scope of comic techniques as well as the powerful poise that I discussed earlier. This reemerges seamlessly to rebalance the play. Colvez has a combination of grace and raw power that seduce us even when the choices in question do not seem to match the rest of the play. She is one of the great supporting dramatic pillars of the more important confrontational scenes.

Further examples of this disillusioning kind are frequent in the later scenes. Act 3, Scene iv in which the speeches of a gardener draw parallels between the health of a garden and national prosperity is a notable instance. This scene should at the very least be a gripping moment in which the queen learns from a ‘mere’ gardener of the incarceration and imminent replacement of the king. Rauck makes the gardener a sort of grotesque character who dons a face mask on which what might be a pig is projected. This could perhaps work in a parallel universe! What truly irritated me was the whiny, high-pitched voice which the actor, for some reason, combines with a poor attempt at a southern (I’m guessing Marseilles) accent. Both are excessive. And despite the beauty of the abstract floral digital tapestry behind him, this strange and unsuccessful decision leaves us with more questions regarding what it is that we are seeing than suspense as to how the queen is going to handle the divulged information. And ultimately, yet another of the minor but fundamental opportunities Shakespeare offers a director to build up narrative tension around the core story arc, is lost or at best diluted.

The Queen (Cécile Garcia Fogel) is also a point of concern. She seems at a complete loss as to who she is and, bizarrely, gives what are surely unimportant words an excessive stress and reverence. She tries to convey a poetic personality and abundant grace while all the while seeming far removed from what she is actually saying. This also gives the edifice of the play, indeed its very being, a good shaking such that we worry for the whole endeavour.

But I cannot finish my assessment with a saddening accumulation of minor details. This would overshadow what the piece gets right most of the time. Atmosphere. Rauck’s Richard does leave us with grand impressions of suffocating scenes from court, billowy foggy Irish moors and ultimately the ruthless combat of two cousins, continually seeking each other out like beasts of prey. Whether with beautiful digital art or the moving rows of seats which magically become mountains or the Tower of London at will, the staging is impressive. This is reinforced by effective use of silk screens and suitably dark lighting of palace halls and great expanses in which we witness murder and destruction. We feel transported to various natural locations of immense scale, feeling great seas surge over us or the intimacy of miniature ornate gardens. And here Alain Lagarde (scenography) and Olivier Oudiou (lighting) must be applauded. Similarly, the scattered and sporadic cheesy folk music somewhat awkwardly disrupts the otherwise beautifully soaring orchestrations of Sylvain Jacques. We come out of the theatre feeling like we have come back from, at the very least, a charming, daunting and unsettling voyage through the British Isles.