“Venham Mais Cinco – The Foreign Eye on the Portuguese Revolution (1974-1975)”

Jeremy Malies in Almada, Portugal

24 July 2025

I doubt if the world’s top news photographers who converged on Portugal when the Carnation Revolution began in April 1974 wore the flowers themselves, but you would think they were sympathetic. This photographic exhibition in the run-down Lisnave harbour district is an evocative, brilliantly curated set of prints with thoughtful explainers. It has even seen some of the photographers (now all, by definition, elderly) return to tour the gallery and talk through the images.

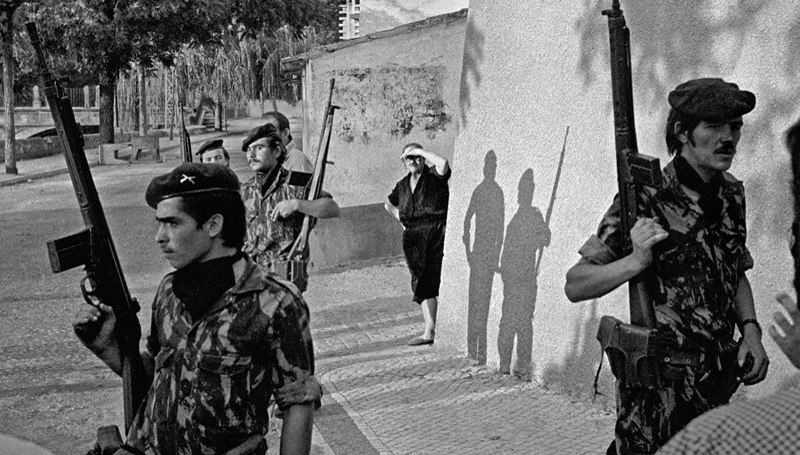

Photo credit: Alain Mingam.

Gamma Rapho.

The title “Venham Mais Cinco” comes from a song by folk singer, protest ballad maker and Jean-Paul Sartre scholar José Afonso. It’s Afro-Brazilian in flavour with a logical if robotic melody. I’m listening to it now, and it doesn’t do anything for me. The track was used as a (second) password on a radio broadcast to launch the unseating of the fascist government.

The exhibition has opened for the fiftieth anniversary of free elections. These emotive images – all printed at least two feet in width – would catch any sentient visitor by the throat. Hard-bitten journalists, many having been in Vietnam and Cambodia, confessed to being moved, with Jean-Claude Francolon (b. 1944) being one of the many who made the logical decision to extend his coverage and move on to Mozambique where he charted the changing attitudes and policies that saw the colony progress to independence. Others would follow the same process in Angola.

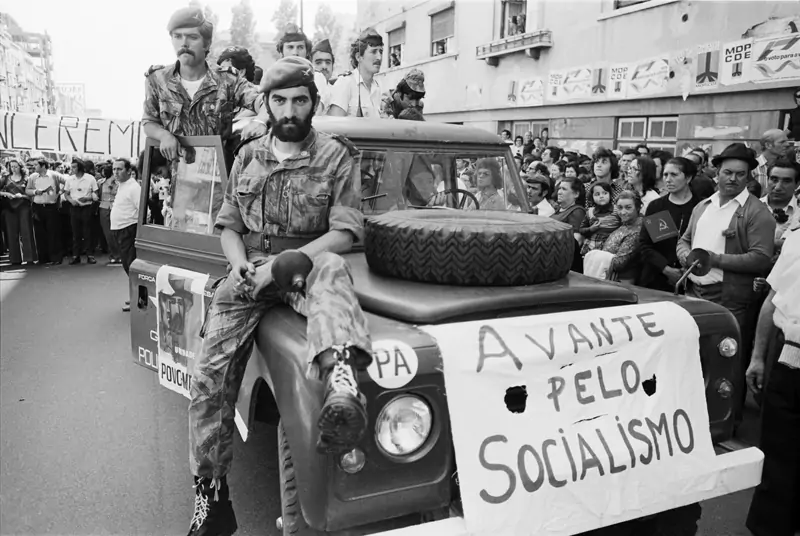

Photo credit: Sebastio Salgado.

Francolon is on record as expressing his sadness at the cyclical nature of Portuguese history which now sees the far-right party Chega with 60 representatives in the 230-seat (no upper house) Assembly of the Republic.

My father once told me that you can tell if a revolution is welcome by watching for children (unbidden by adults) handing out sweets and flowers to the liberators. Here the exchange is two-way. Paola Agosti snaps a middle-ranking officer presenting a pig-tailed girl with a spray of orchids, and she performs (perhaps unconsciously) a half pirouette by way of thanks. No stranger to documenting fascism, Agosti had been in Salvador Allende’s Chile a year earlier. Now 78, I hope she has returned to Portugal to see her image in this context.

Photo credit: Paola Agosti.

There is satisfaction in the faces of the soldiers and junior officers who were components in the uprising, but not much triumphalism. You sense an awareness of how much work remains to be done across Portugal and in the parts of Africa that had been colonized.

A lantern-jawed officer in his thirties under a ballistic helmet stands on a Humber-type vehicle and wields a German-made Schmeiser machinegun, but with no sense of menace. He could be a commuter on a tram carrying his briefcase. Carnations obviously bloom in April in Portugal. Most of the photos are black and white; the photographers use colour primarily to portray these flowers which range from flamingo to candy-floss pink. Could it all have been that peaceful? Well, possibly. I soon come across a photo of a similar vehicle where the driver is reading the back page of News Diary with the kind of relaxed body language that suggests he’s checking what won the 2.30 at Marechal Carmona Park.

There are many sailors in the crowd scenes; it should be remembered that Carlos de Almada Contreiras, a captain in the Portuguese Navy, was a strategist in the revolution. Officers on the Almirante Gago Coutinho sailing off the Lisbon coast refused to fire at the city. Sailors stand observing the tanks, and jostle for space in a good-natured way with civilians of their own age who are sporting the latest craze – tie-dye T shirts. A trooper, barely out of his teens, has been given a tumbler of wine by a woman in overalls who is dispensing the stuff from a pail. He drinks with connoisseurship as though it has been offered to him by a sommelier at a top hotel on the Calçada do Duque in Lisbon.

Photo credit: Uliano Lucas.

A mid-ranking PIDE (secret police) functionary in what might as well be a cardboard suit is escorted away. He appears to have bumped into a few objects and had accidents while shaving. And he looks resigned. But you know he will not come to significant harm; the revolution was indeed more or less bloodless in execution and follow-up. Another suspected agent who has been to a better tailor is led down a flight of street steps while a Mitra handgun is prodded into his shirtfront. Jubilant civilians in plaid cardies perch on the bonnet of a Morris Marina while troops in white combat helmets observe them indulgently. A gargantuan man weighs down his Vespa-style scooter and even has a pillion passenger.

In Angola, a man lies on a hospital cot having had his right leg amputated at the knee. What remains of the leg is balanced on a can of powdered chalk. He stares (terrified) into space, perhaps pondering what kind of prosthetic he can expect and what the future holds.

Back in Lisbon, a sailor stands guard in front of shelves of box and ring binder files. There was a general insistence that the atrocities under the fascist regime should be documented. A scholarly-looking civilian with a tab on prepares to sift through the paperwork.

Photo credit: Michel Puech.

Prominent dissidents Domingo Abrantes and Conceição Matos are in my mind after I saw them on stage in a play I have reviewed. I wonder how quickly they were released. Half a dozen people perch on a Citroen C-60 with a placard calling for public judgement of fascists. A brave mixed-ethnicity clergyman (his superiors aligned largely with the Estado Novo) leads a group with a placard calling for an end to colonialism.

A man resembling Alan Whicker in a Homburg hat peers at a news kiosk to read the front page of People’s Voice. Photographer Gilbert Uzan (celebrated for a picture of Nadia Comăneci two years later at the Montreal Olympics) is no doubt amused that despite the gravity of what is going on and the profusion of hard-news print media, there are still girlie magazines on the bottom shelf. A trio of women dances through a textile factory with one carrying a decanter of spirits. A newborn is bounced on its mother’s knee in a canteen.

A shelled building is full of tin helmets; a drum set is scattered in the foreground. A promotional calendar for a vinyl coating company has been shot at – I can’t quite make out the date. “End colonial wars!” is the one legible placard among hundreds at what could be a Mayday Parade in New York. Detail in the prints is exceptional; I wonder if anybody was shooting medium format.

Photo credit: José Sanchez Martinez.

Collectivized farming was one of the first post-revolution initiatives, and piglets are pictured being inoculated. A woman in a tea cosy hat who could have leapt out of a Bruegel or a Donald McGill postcard calms a sizeable sow before its jab. The optimism and camaraderie remind me of the early pages of Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia and the Ken Loach film Land and Freedom though here the outcomes were positive.

Photo credit: Jean-Paul Miroglio.

The elderly and infirm are shepherded to ballot boxes in what are transparently free and fair elections. Their younger neighbours look on with contentment and optimism. A spindly woman trudges purposefully uphill past murals of Marx and Lenin. Kindergarteners in gingham dresses carrying dolls that they have found at an abandoned arable farm in the heart of the country treat the lens of Fausto Giaccone’s Nikon F2 to basilisk stares. Fausto, who concentrated on documenting agrarian reform here, has just told me by email about the camera and his Kodak Tri X film. It’s perhaps my favourite image in a style that sits midway between Walker Evans and Vivian Maier. As with the other photographers who are still alive (my survey here suggests top news photographers are long-lived) I hope Fausto sees his work in context at this extraordinary exhibition.

Open from 11:00 to 19:00 until August 24. Avenida da Aliança Povo MFA, Mutela Business Park, Almada, opposite former Lisnave Shipyard. Free admission.