“The Tempest”: Jermyn Street Theatre

Neil Dowden in the West End

1 June 2020

Prospero’s epilogue in The Tempest in which he renounces his magic — “Now my charms are all o’erthrown … Let your indulgence set me free”— has often been taken as Shakespeare’s farewell to theatre in what was his final solo play. ln the moving production at Jermyn Street Theatre, the words took on an especially poignant quality because — with the rapid spread of Covid-19 — this turned out to be one of the very last performances in a London theatre before everything shut down. Before the show, the theatre’s artistic director and the show’s director Tom Littler gave a short, impassioned address to the audience thanking them for their support, but there was a feeling that the coronavirus storm was about to break in the capital.

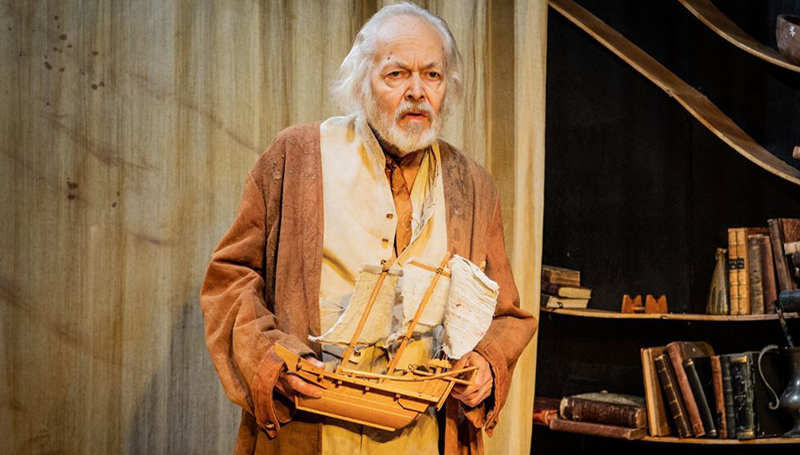

Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The storm scene at the opening of the play is imaginatively staged like a piece of minimalist magic on the theatre’s tiny stage. Michael Pennington’s exiled magus Prospero holds a miniature version of the vessel for which he has conjured a tempest and mouths the words of the mariners who are being shipwrecked behind a sail-like curtain as if this was a vision in his own mind. His usurping brother Antonio, Duke of Milan, and his cohorts are finally within his power — though whether for revenge or forgiveness is in the balance.

In the original, Prospero and his daughter Miranda have been stranded on the island for twelve years, and she is now a fifteen-year-old adolescent. But here the time elapsed is evidently much longer as Kirsty Bushell’s Miranda is quite a lot older, though still girlishly innocent. And her relationship to a rather frail Prospero seems at times almost to be that of a caregiver. This is a departure from the traditional presentation of Prospero being a sternly benign patriarch who rules the island with a rod of iron – or at least with a magic wand. He does, however, make sure that airy sprite Ariel and earthy slave Caliban do his bidding while he teaches his enemies a lesson they won’t forget.

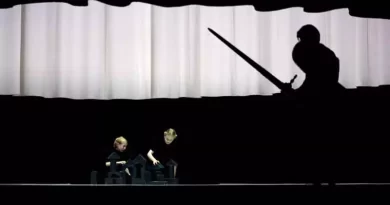

Tam Williams as Caliban.

Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The production is partly inspired by the seclusion of the Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin on the Polynesian island of Tahiti, with its colonial implications. The design by Neil Irish and Anett Black features a set lined with wave-like curving shelves bearing books, knick-knacks, and pagan wooden carvings — a nod to Gauguin’s primitivism. Littler works wonders with limited resources to evoke a dreamlike, allegorical ambiance which is founded on Shakespeare’s mythic poetry.

As one of the greatest living Shakespearean actors — who has probably played more of the Bard’s leading roles than anyone else in a fifty-plus-year career overwhelmingly dedicated to the theatre – Pennington speaks the verse with beautiful lucidity, as always. His Prospero is much more melancholic than bitter: a wise, gentle scholar who never looks likely to wreak vengeance on his treacherous brother, even if at the end when the rightful hierarchy has been restored there is notably no reconciliation between them.

Prospero has an unusually warm relationship with Ariel, given a vivacious feminine presence by the multi-talented Whitney Kehinde who sings, dances, and impersonates a succession of goddesses in the masque scene. Tam Williams seems underpowered as the resentful, masked Caliban, also doubling as Ferdinand (nicely linked by having both characters’ hands bound when doing Prospero’s hard labour). But Ferdinand’s budding romance with Bushell’s Miranda is unconvincing as first love with both actors so mature. The comic subplot wherein Caliban tries to gain control over the island with the help of Richard Derrington’s amusingly drunken butler Stephano and Peter Bramhill’s drolly ad-libbing jester Trinculo is played as a parody of the coup in Milan – but this time Prospero prospers.

As if Jermyn Street Theatre didn’t have enough financial problems to cope with due to its enforced closure, during lockdown it was discovered that a water pipe in a neighbouring basement had burst, flooding the theatre’s workshop, stores, dressing rooms, and offices, and destroying much of the props and costumes for The Tempest. Despite all this, the theatre has confirmed that — when eventually given the go-ahead – it intends to reopen with this fine production. The show must — and will — go on.