“The Merchant of Venice 1936” at Criterion Theatre

Neil Dowden in the West End

26 February 2024

First seen at Watford Palace Theatre a year ago, the nationwide tour of The Merchant of Venice 1936 reaches its climax in the West End – though its setting is the East End of London, a transposing of Shakespeare’s play to the great political and social unrest of the 1930s. It’s a brilliant idea, brilliantly executed by co-creators Tracy-Ann Oberman (who stars as Shylock) and director Brigid Larmour to set the play against the background of the Battle of Cable Street when fascists marching through the Jewish community were met by fierce resistance. And, sadly, it touches a raw nerve now with the rise of the far right and antisemitism once again.

Tracy-Ann Oberman as Shylock.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

The Merchant of Venice has always been a problematic play to stage because of its awkward mixture of romantic comedy with dark themes of racism and revenge, the love between Portia and Bassanio (in Belmont) contrasted with the conflict between Antonio and Shylock (in Venice) – though they are of course connected. In this adaptation, the emphasis is very firmly on Shylock’s story, with most of the heavy cuts in this two-hour version coming from the Belmont scenes – and the tragic mood predominates over the comic. But the gender-swapping of the Shylock role makes as much impact as the historical context in which the drama is enacted.

The show begins with a short added scene in which we see members of the Jewish community enter raising their arms in welcome to the audience before sharing a convivial, ritualistic meal together, speaking Hebrew (translated into English). But the relaxed mood is shattered by the sound of glass breaking and the projection on the back wall of newsreel of Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists’ Blackshirts storming into the area.

Antonio, Bassanio and their circle are upper-class Englishmen who despise and denigrate Jews like Shylock, though that does not stop them from borrowing money from them if they need to. Here, Shylock is presented as a hard-working single mother with a young daughter trying to keep her business going in a hostile male, Anglo-Saxon environment.

Despite her anger at the despicable treatment she has received, she agrees to a loan to Bassanio with Antonio as guarantor without this time charging interest in a gesture of amity – the bond of a pound of flesh for non-repayment is not meant seriously at this point. It becomes deadly serious after her daughter Jessica elopes (taking much of her jewellery) with Bassanio’s friend Lorenzo, converting to his Christianity, as it becomes clear to Shylock that they are all out to persecute her.

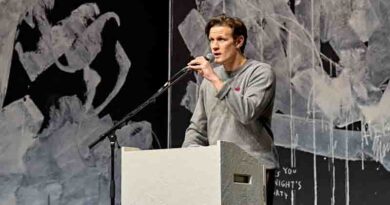

Tracy-Ann Oberman as Shylock.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

This circle of enmity extends to Portia’s household, where Lorenzo and Jessica end up – and of course for which Bassanio needs the loan in order to obtain the chance of winning the rich heiress’s hand. The comic casket scenes are here informed not only by Portia’s desire to help Bassanio to guess the riddle correctly, but by her overt distaste for the other, foreign suitors – in particular her racist remarks about the Indian Maharajah (replacing the Prince of Morocco). She also cold-shoulders Jessica, whom she evidently regards as inferior. And Gratiano, who becomes betrothed to Portia’s maid Nerissa, is an antisemitic yob.

The court scene where Shylock is outwitted, then humiliated, is painful to watch. Backed by a large Union Jack, this is not an impartial place of justice – Shylock is treated differently as an “alien”, not only being deprived of most of her possessions and livelihood, but being forced to renounce her religion. She wanders into the auditorium carrying a suitcase like a refugee, but returns to sit at the back of the stage while the Belmont celebrations take place.

The show ends not with the usual lovers’ reconciliation after Portia and Nerissa reveal they were the lawyers disguised as men in court and restore the engagement rings to their embarrassed fiancés, in a display of elitist triumph. In a rousing coda, Shylock and her community move forward to the front of the stage chanting and carrying a banner declaring “They shall not pass”, as images of the Battle of Cable Street flicker across the screen. They encourage the audience to stand in solidarity – which most do – while speaking as herself Oberman pays a moving tribute to her great-grandmother and those like her who resisted the fascists.

Larmour’s powerful production follows through its concept consistently and cogently, evoking a time of political extremism, as we gradually see more characters on stage wearing BUF armbands and uniforms. Liz Cooke’s design includes inflammatory posters and antisemitic graffiti on the brick walls of East London terraced housing, which is screened by a curtain when the action moves to the privileged Belmont.

The splendid cast speak Shakespeare’s blank verse with great clarity. Oberman is magnificently defiant as a Jewish matriarch Shylock, cast down by her oppression but not broken. As an overprotective mother rather than father there is a different, more sympathetic dynamic to the hurt of losing her daughter, while we see her shudder in relief when she is prevented from taking a pound of Antonio’s flesh.

Despite not being so much the centre of attention, Hannah Morrish as Portia also makes a strong impact as a posh-accented sloane who defends her class interests. Gavin Fowler’s Bassanio is a charming but shallow playboy who takes advantage of Raymond Coulthard’s smitten Antonio whose urbanity co-exists with deep-seated racism. Jessica Dennis plays Nerissa as well as the impudent Launcelot Gobbo character rewritten as Mary, which doesn’t work as the comedy falls flat – a rare misfire in a show that makes The Merchant of Venice feel like a play for our time.