“The Human Voice”: Harold Pinter Theatre

Neil Dowden in the West End

24 March 2022

Jean Cocteau’s 1930 monodrama The Human Voice about a woman’s last phone call with her ex-lover is a showcase for actors. There have been many stage and screen versions over the years starring the likes of Anna Magnani, Simone Signoret, Ingrid Bergman, Liv Ullmann, Sophia Loren, and only last year Tilda Swinton in a short film by Pedro Almodóvar. Now in the West End, Ruth Wilson rises splendidly to the challenge. She is reunited with director Ivo van Hove after the success they had with their radical reinterpretation of Hedda Gabler at the National Theatre in 2016/17. But while Wilson demonstrates great technical virtuosity her emotional engagement with the audience is limited by van Hove’s over-stylized, minimalist production that distances us from the raw feelings at the heart of the play.

Ruth Wilson in The Human Voice.

Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

As a piece about separation and loneliness, the loss of in-person contact and warmth of companionship, The Human Voice fits well into our recent period of covid lockdowns and restrictions where keeping in touch with loved ones by phone or electronic device has often been a lifeline.

It takes the form of a dramatic monologue with ‘She’ talking on the phone to her unseen and unheard former lover who is about to marry his new girlfriend. At first she seems to have accepted the situation, cheerfully making arrangements for his letters to be returned and telling him he must take the dog as it is pining for him. But it soon emerges that really she is heartbroken and has been desperate to hear his voice again. This is not a mutual break-up – he has left her and she can’t bear to be without him.

The woman lies about what she is wearing – not a blue dress but casual clothes – and tells him she can’t find the shoes he has asked for but we see her embracing them. She confesses she hasn’t just got home after being out with a friend but has stayed indoors for the last two days depressed and had even taken an overdose. She says – unconvincingly – she has now got over these excessive feelings but later we see her vomiting and taping a poster to the window, “Come Home”. While they are temporarily cut off she continues talking to him in an imaginary conversation that suggests a mind disturbed by grief. Could it even be that this is all taking place inside her own head?

This is clearly a contemporary setting as the woman is wearing a Tweety Pie sweatshirt and tracksuit bottoms, while she is using a cordless phone. This makes the idea of her being interrupted by other callers on crossed lines or talking to an operator in a telephone exchange (as in Cocteau’s original script) rather absurd, but the periodic losses of connection ring only too true. There are occasional melodramatic lurches in tone, but a more serious issue is the woman’s all-consuming emotional dependence on a man – “You are my only breathable air” – which may seem forced today.

Ruth Wilson in The Human Voice.

Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

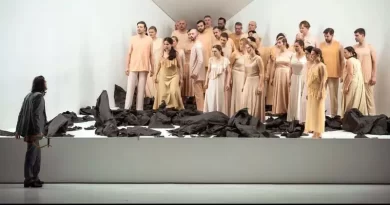

Designer Jan Versweyveld’s spare set consists of a sealed box with a blank back wall, no furniture, and a sliding glass door at the front which evidently opens out on to a narrow balcony high above the street, judging by a rippling breeze and the sound of traffic. Although this is supposed to be the woman’s home it suggests more a room in a mental hospital, which is reinforced by a clinical light that sometimes turns a lurid yellow hue. There is a strong sense that she is isolated, imprisoned in her depression. But for a play that wholly depends on one actor involving the audience in the character’s feelings of desperation at the end of her love affair, it does seem perverse to cut her off from us like this, communicating via a microphone.

Van Hove’s adaptation was originally produced by International Theatre Amsterdam in 2009 in the Dutch language. His 70-minute production is longer than usual for this play and although still short it does at times feel a bit strung-out. In particular, at one point Wilson remains frozen, slumped on the floor with her hands spread out on the wall, while the whole of Radiohead’s “How to Disappear Completely” plays out over several minutes. A number of pop songs are used to punctuate the sections of speech (as well as some mournful cello music) – apparently played by the woman herself on an iPhone – though they seem somewhat gratuitous.

Wilson gives a superbly nuanced vocal performance. We hear her – the human voice – before we see her and she carries on talking after disappearing from our sight on either side before rushing back to centre stage. But there is physicality too: restlessness is mixed with moments of stillness, even lethargy, as she paces around her “padded cell” liked a caged animal, before curling up in pain. Wilson runs the gamut of emotions: a mélange of laughter and tears, whispering and shouting, flirtation and anger, tenderness and sadness. It’s a convincing account of a “one-way” telephone conversation where one can usually guess what the man is saying by the way she reacts. And there is a real impression of an intimate relationship in which the two have known each other well over five years – but that time has come to an end with her ex-lover moving on while she cannot.

Ruth Wilson in The Human Voice.

Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.