“The Hot Wing King” at National Theatre, Dorfman

Jeremy Malies on the South Bank

24 July 2024

What is it with food on stage now? Everything from Next to Normal to Phaedra to multiple productions of David Eldridge’s Beginning feature cooking and often in real time. Most notable (in an industrial kitchen) is the recent Clyde’s, a play with which The Hot Wing King has similarities as people express themselves through preparing innovative if not always successful dishes.

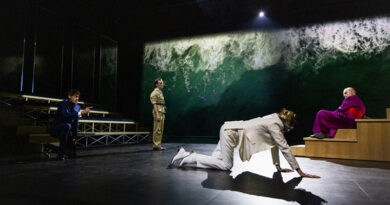

Kaireece Denton and Kadiff Kirwan.

Photo credit: Helen Murray.

Here, Katori Hall’s treatment of six Black men in Memphis (four of them are gay) has the group preparing entries for a spiced chicken-wing contest the next day and we see steaming pots of marinade in Rajha Shakiry’s two-level set. I’m hardly a bloodhound and sensed nothing but others took pleasure in buttery Parmesan wafting into the stalls. With the show going up ten minutes late, I worried that the cauldrons of sauce would spoil.

Even though all the characters are Black, I don’t think that the core of the play is ethnicity. Hall was prompted to write it by the experiences of her brother and perceptions of Black masculinity, but the themes strike me as deeper-lying. Hall’s script prompts us to think about sexual orientation, how it can change expression mid-life, and the fleeting prospects of happiness that this can offer amid pressures from a previous family set-up.

Cordell (played by Kadiff Kirwan) is a father of two who has belatedly acknowledged that he is gay and separated from his wife. Unemployed, he is in a new and loving relationship with Dwayne (played by Simon-Anthony Rhoden) who is a manager at a hotel. Cordell is an accomplished amateur chef.

All the men attend church nearby and I wondered how they and their preachers deal with notorious verses in Leviticus, Jude, and Romans. The church background contributes to some of the best gags amid the banter. I howled as one of the men says the next service may be marred by squabbling, possibly “a laying-on of hands – and not in a godly way!” Dialogue morphs from banter to profound considerations of male sexuality and its modes of expression as well as fatherhood issues (notably alimony and access) in relation to Cordell’s off-stage children.

Kairecce Denton and Dwane Walcott.

Photo credit: Helen Murray.

The presentation style occasionally smacks of a television soap, but this is deliberate and tongue-in-cheek from director Roy Alexander Weise. It worked amid the party atmosphere on opening night, with entrances heralded by soap-style bursts of music. The whole house swayed to a full rendition of Luther Vandross’s “Never Too Much”. I could have done with even more music. Later, two characters pick out a few chords on the upright piano but neither really played it which frustrated me.

Shakiry’s design pays attention to detail without being fussy. The home is shown to be luxurious with an Airbnb-style guest bedroom on the upper tier and extensive corridors giving a sense of depth. The island kitchen even spins to reveal the oven in which the all-important chicken wings are prepared.

Weise and the cast are generally deft with the physical comedy as the characters give skin and high-five each other, but the basketball routines (there is a hoop front stage right) are dire. I marvelled at which simple feint or dribble the men would mess up next and don’t believe it was intentional comedy. This might improve during the run but none of the characters will be getting game time for the Grizzlies at the nearby FedExForum. Olisa Odele as Isom (Big Boys on Channel 4) looks magnificent in his Grizzlies jersey. Shakiry is also responsible for the costumes and bedecks the men in vile Hawaiian shirts for the day of the hot-wing contest.

Isom, something of a caricature with his bling and Louis Vuitton man bag, has a plaintive line as he bemoans never getting beyond a one-night stand even with people he likes. There are many similarly intense authentic moments here. A scene in which Dwayne tells Cordell that he has only been a jobseeker in the city for a short time and will land on his feet (meanwhile Dwayne’s pay cheques can cover the bills) has precision and dignity. Hall’s script is impressive when she injects edgy crude non-jokes that betray the homophobia of Dwayne’s brother-in-law TJ (a brooding hulking Dwane Walcott) when he reluctantly entrusts his son to the men as a lodger.

I’m surprised that this won a Pulitzer Prize after its initial 2021 off-Broadway run. But overall I was charmed despite the hefty 185 minutes with interval making for a long night. It struck me that there were more logical (and even moving) points at which the story might end earlier.

Is there a parallel I’m missing? Are the chicken wings an overarching metaphor? I don’t think so, but they are a means through which the men seek creative perfection. As with Hall’s best play, The Mountaintop, which depicts Martin Luther King Jr. in a motel (Memphis again) on the eve of his assassination, the points here are made through a specific backdrop not artifice and figurative language.

Cajun Alfredo wings with bourbon-infused crumbled bacon are the signature dish on which this play revolves. Stopping at KFC in Waterloo Arches for a six-piece bucket as is my habit after the National, I did wonder if staff in chicken shops along the South Bank were receiving any bizarre orders.