“The Homecoming” at the Young Vic

Neil Dowden on the South Bank

11 December 2023

Matthew Dunster’s compelling revival of Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming opens in a fog of dry ice that befits this murkily ambivalent 1965 domestic drama. Often regarded as Pinter’s best play, it is regularly revived but it is showing its age a bit now especially in terms of sexual politics. This half-naturalistic, half-stylized production retains the period setting while suggesting that the dodgy doings on stage are more of a Freudian psychodrama than a literal sequence of events.

Joe Cole and Jared Harris.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

It all takes place in the living room of an East London working-class home where four men spar with each other in a testosterone-filled atmosphere devoid of a female presence since the death of wife/mother Jessie. Patriarch Max, a retired butcher, puts down his younger brother Sam, a chauffeur, implying he is homosexual, also locking horns with his pimp son Lenny, who mocks his ageing father’s declining physical powers, while youngest son Joey is training as a boxer.

Into this den of toxic masculinity arrive eldest son Teddy, who’s been working as a philosophy professor in America for the last six years, with his wife Ruth – a homecoming that leads to a characteristically Pinteresque power struggle where family and business mix queasily.

The misogyny of the men is all too evident. However, the way in which Ruth seems to relish the sexual attention focused on her (“Look at me”) and use it to her advantage while agreeing to prostitute herself (and leave her husband and three sons in the States) is a provocative twist that is hard to stomach. Even if she seems to be calling the shots by the end – making non-negotiable demands bound in a contract – her job will be sexually pleasing men, as well as mothering them. She may be taking over the roles of Jessie – but on whose terms?

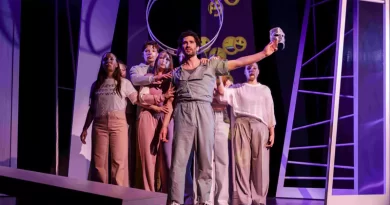

Lisa Diveney and Joe Cole.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Dunster’s production emphasizes the way the men need a female influence in their empty lives – divided by macho competition – though there are strong hints that this was always a dysfunctional family even when Jessie was alive. And there are expressionistic touches implying all is not what it seems on the surface, especially in Sally Ferguson’s dramatic spotlights on characters in flashback memory or physical combat on the circular rug centre stage – is this actual or figurative?

Moi Tran’s design also mixes it up, with 1960s clothing and solid period furniture – including sideboard plus soda siphon and drinks, sofa and chairs, a gramophone playing jazz records – that looks strangely spaced out and frozen in time. The open staging may undermine the claustrophobic nature of the piece, but the stage becomes more of an arena for the battle between the protagonists.

In a welcome return to the theatre, Jared Harris (who’s had prominent roles in Mad Men, The Crown and Chernobyl) gives Max the intimidating presence of a bully ready to use his stick as a weapon, a self-aggrandizing and delusional man who claims to be an expert in things he is ignorant of and who sentimentalizes his abusive fatherly behaviour in the past. Joe Cole is restlessly unpredictable and sardonically confrontational as Lenny, but he fails to convey the true menace needed for the role (despite his Peaky Blinders credentials).

It is clear from the outset that all is not well in the marriage of Robert Emms’s weak, passive Teddy (who is not as enlightened as he claims) and the dissatisfied Ruth (cut off from her roots), played persuasively by Lisa Diveney as a shrewd operator rediscovering her agency through her sensuality.

David Angland plays the inarticulate Joey, a brute with a surprisingly soft centre, and Nicolas Tennant gives a superb performance as the most sympathetic character Sam who tries to stand up for some sense of decency amidst the sleaze.