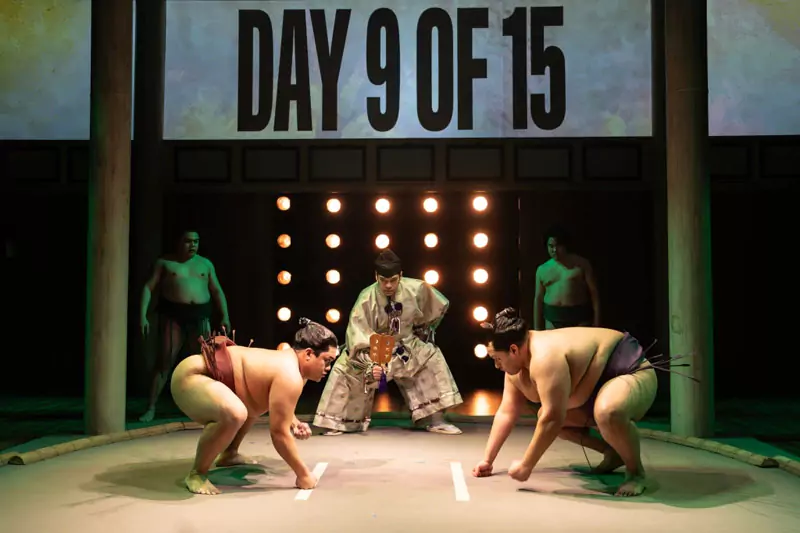

“Sumo”, Public Theater in New York

Glenda Frank

27 March 2025

This play tells the poignant compelling story of the improbable rise of a boy – raised in poverty by a single mom – to national recognition. The production directed by Ralph B. Peña with script by Lisa Sanaye Dring towers over the season’s competitors.

Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

Sumo takes the audience into a world that is at once familiar and exotic. Dring has a knack for introducing disparate elements with a light touch but in pivotal moments. Into this almost fairy-tale tapestry, she weaves sharp, realistic, sometimes startling detail as well as references as contemporary as karaoke. And no, you don’t have to like wrestling, but if you are curious or excited about Japanese culture or Sumo wrestling, which is an art unto itself, this is a must-see. Sumo wrestling, with its strong ties to the Shinto religion, dates back over two centuries and is the national sport of Japan.

Sumo is a coming-of-age story, the hero’s journey to spiritual awakening through sports. Small and slim, unlike traditional Sumo wrestlers, Akio (Scott Keiji Takeda) is slighted and ignored by the team of elite athletes. When Mitsuo (David Shih), the top rikishi (wrestler), chooses the boy to serve him, the apprenticeship turns into gratuitous brutality. But Akio soldiers through. Each step of the way, Akio’s choices define him.

As the play unfolds, we learn how uneasy the men are. They share a life together as heya (stable) mates and as rivals, tasked with training the newcomers, who may replace them if they lose bouts.

Akio’s rise from the menial tasks of an initiate through the hazing and new friendships mirrors his mastery of the sport and, more importantly, of himself. As we discover the world of sumo wrestling through his eyes, the lives of his team mates also come into focus: the men who have found forbidden love, another who discovers that an unexpectedly better life awaits him after failure, and the champion whose motivation is women and fame.

The Sumo wrestling competitions (honbasho) are brief but totally engaging, at once familiar and strange (James Yaegashi and Chelsea Pace, direction). That combination is a powerful, exciting lure. Although the actors lack the traditional sumo heft, they make us understand how weight, balance, timing and ruses define the battles. The soundtrack by Shih-Wei Wu on taiko drum, on a level above the stage, adds excitement.

Sumo as a locker room drama is rich in traditional Japanese costumes (Mariko Ohigashi) and customs. But unlike similar dramas, the Shinto religion plays an important role as the oversized athletes struggle to find the balance between the discomfort of physical injury, their desires, and their dedication to the craft. The Shinto religion with its strict rules are represented by three narrator-priests (Kannushi, divine master of ceremonies), whose ritualistic grandeur add a unique dimension to Sumo.

Also admirable were the set design by Wilson Chin, especially the fighting ring; lighting by Paul Whitaker; and projection design by Hana S. Kim. The drama was co-produced by Ma-Yi Theater Company and the Public Theater.