“Saul”, Handel, Glyndebourne

Simon Jenner in East Sussex

24 July 2025

Glyndebourne revives Barrie Kosky’s 2015 vision of Handel’s early oratorio Saul, now directed by Donna Stirrup with choreography by Merry Holden. There are tweaks but no meddling with the core offering. Oratorios unlike operas come with choruses attached. Glyndebourne’s Handelian chorus turns troupe; they dance and glide, and in the case of the six dancers they tumble.

©Glyndebourne Productions Ltd.

Photography by ASH.

With 42 operas to choose from, many of them languishing masterpieces, this looks on the face of it to be a quixotic choice. Among the oratorios, Saul from 1738 is full of dour musical power but few florid showstoppers. But … there is that singular love triangle featuring brother and sister: David and Jonathan and Michal too. Oh, and Saul himself who mutters words never heard by Handel. “I am king still!” comes as curtain to Act One; and sometimes there is gibberish.

Every accent Christopher Purves utters as Saul falls like a morsel of stone, quarried. He is frighteningly lucid in Saul’s craze which begins early with noticing how female chorus members fawn on David. “With rage I shall burst his praises to hear!” Purves is equally clear channelling the shade of terminally tetchy prophet Samuel: “Why hast thou forc’d me from the realms of peace” calls on a spectral edgy timbre. The thrilling chorus led by Aidan Oliver is garbed in an eighteenth-century century rainbow coalition; but three male leads, until two strip off to their impressive pecs, are in dinner jackets. Work that out. Are they keepers to a time-travelling asylum where Handel, in a hallucination, believes he has been cast?

The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, conducted by Jonathan Cohen from the keyboard, features an uncredited harp, but the star of these punchy, stylish forces is Matthew Fletcher, rising out of the cellarage as Act Two starts astride a revolving chamber organ. Metaphors aside, it’s one of three “maggots” Handel was reportedly obsessed with in Saul. A mini organ concerto helmed by Handel was a crowd pleaser, but it distilled the following act. There is a sonorous pluck from Pablo FitzgGerald’s theorbo, but the ensemble throughout is inspired. No more so than in the famous Dead March where Harry Rylance’s organ and carillon continuo throb to prominence. Handel’s carillon, a pitched percussion of 23 bells played on a keyboard, was just as obscure then as now: another “maggot” Handel insisted on, rising at climactic moments.

©Glyndebourne Productions Ltd.

Photography by ASH.

Indeed “Mr Handel’s head is full of maggots” reported his new collaborator, the pompous but dramatically gifted Charles Jennens. Saul, fourth of Handel’s oratorios, was written at a crossroads. In 1739 Handel found that his 20-year run as an Italian opera composer was dead. There were brave twitches but London pronounced. Writing feverishly, Handel repurposed a Trio Sonata as a sprightly overture that has nothing to do with Saul. As ever he occasionally snatched from others, including Bach’s dead predecessor at Leipzig, Johann Kuhnau. He probably knew of the huge success Marc-Antoine Charpentier enjoyed in 1688 with his Tragédie Biblique David et Jonathas. But few works are as suggestive of Handel’s mind as Saul.

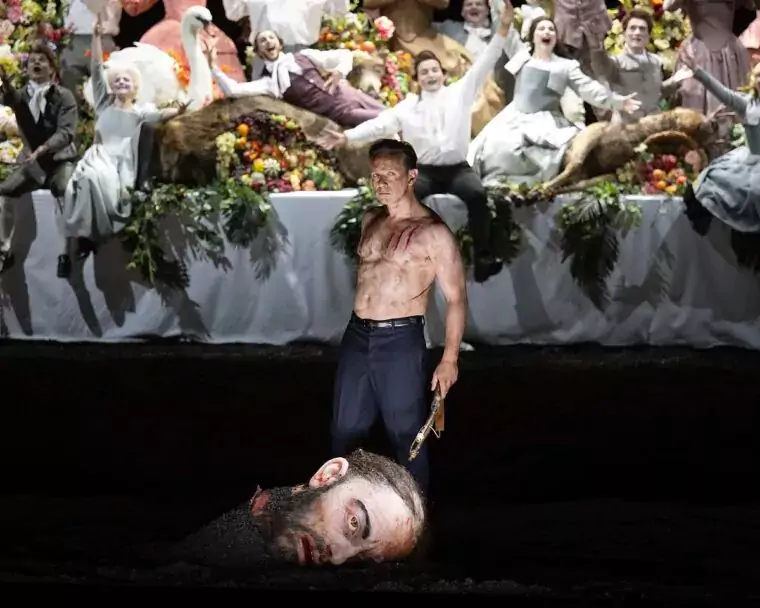

The famous biblical story of David, seen here at the outset with Goliath’s massive severed head as if hewn from a statue with arteries, can be read cruelly. David is a catalyst who unwittingly destroys a family or dynasty: and from the ruins engenders his own. King Saul, initially delighted with this sheepish saviour, offers him his eldest daughter’s hand. But Sarah Brady’s Merab haughtily disdains him in her first aria: “What abject thoughts a prince can have!” She continues with “Yet think on whom this honour you bestow” with venom and evoking (if not vocalising) sprezzatura.

Brady has two superb solos later. In Act Two, when she’s melting: “Mean as he was, he is my brother now”; and Act Three’s lament: “From this unhappy day”. Brady’s range from dark mezzo to soprano heights stamps her character quite late, but you see why Handel wrote this part for his lead, the great Cecilia Young. Young, star of operas like Ariodante, suggests just how operatic Saul might have seemed in 1738. Brady seizes her arias out of that tradition.

Soraya Mafi’s Michal though is a delight. Highly mobile, joyous, making no disguise of throwing herself at David from the start (“He comes, he comes!” and “O godlike youth”), this Michal in a shimmering air-blue gown straight out of Gainsborough’s “Mr and Mrs Andrews” skims round him; as much as Merab tends to stay put. Mafi’s warmth and elegant abandon are the most uplifting things in this oratorio. Her arias flow through. Deliciously outrageous she throws herself on her back, legs wide in her aria: “A father’s will has authorized my love”. She certainly gets the best laughs, then after such vocals applause for her lyric soprano now stratospherically, let’s say consummated. Her role darkens though: first in “No, no, let the guilty tremble” when she hustles David away from danger (this after their duet “At persecution I can laugh”). Then comes her elegy for the love between David and her brother Jonathan: “In sweetest harmony they lived” which takes some beating for complaisance.

lestyn Davies as David emerges slowly, though his presence draws you in from the start. Vocally Davies’ counter-tenor is as distinct as Purves’ baritonal Saul. Though David starts with “O King, your favours with delight” he is often duetting with Jonathan or Michal (another gem is their first duet of declaration “O fairest of ten thousand fair”, a thunderclap of emotional freedom). Otherwise there are musings: (“Such haughty beauties”) or blind obedience: “Your words, O King” both from Act Two. From Act Three emerges the lament for Jonathan: “Brave Jonathan his bow never drew” which comes after a nasty incident of avenging the mercy killing of Saul on a luckless foe: “Impious wretch, of race accurst!” It’s in the latter part of Acts Two, and Three that David emerges from Saul’s vocal shadow.

Linard Vrielink’s Jonathan suggests extreme care for his art at all times: shaded, fraternal and here amorous with tender loyalty. To launch a thrillingly dark aria such as “Birth and fortune I despise!” is a lover’s declaration, a sharp rebuke to Merab. And after duetting with David (“Ah, dearest friend” which has them rolling together) the “But sooner Jordan’s stream, I swear” declares love straight out of Acis and Galatea. Arias with Saul are fraught – moving from “Sin not, O King” agitating fright, to when Jonathan thinks he has persuaded Saul: “From cities stormed, and battles won.”

Liam Bonthrone succeeds in roles like the high Priest, tromboning a bass-baritone in “Go on, illustrious pair!”; whereas in the role of Doeg he slithers in court flunky recitative. Ru Charlesworth’s Witch of Endor gets the seethingly magnificent “Infernal spirits”, emerging in hideous teats between Saul’s legs.

Saul is choral though and this is Glyndebourne. The chorus thrill in Act One with “How excellent thy name, O Lord” and the Allelujah moment of “Preserve him for the glory of Thy name”. Handel wanted to end the oratorio with triumph. Jennens dissuaded him. What we get is the gritty “Gird on thy sword, thou man of might”; it’s a masterstroke.

Katrin Lea Tag’s set invokes Sir John Tenniel’s drawings for Lewis Carroll with banqueting tables. The production is lit pitilessly by Joachim Klein. A curtain allowing set changes merely shifts the table at right angles. During the summoning scene, the cindered ground invokes the barrenness of Saul’s kingship and temporary humiliation. Otherwise, this oratorio nearly makes it into Handel’s operas. It certainly enjoys a classic operatic triangle. And this unpredictable audience (“Is this the one with Goliath?”) love it.