Theatre critic Michael Billington interviewed by Dana Rufolo

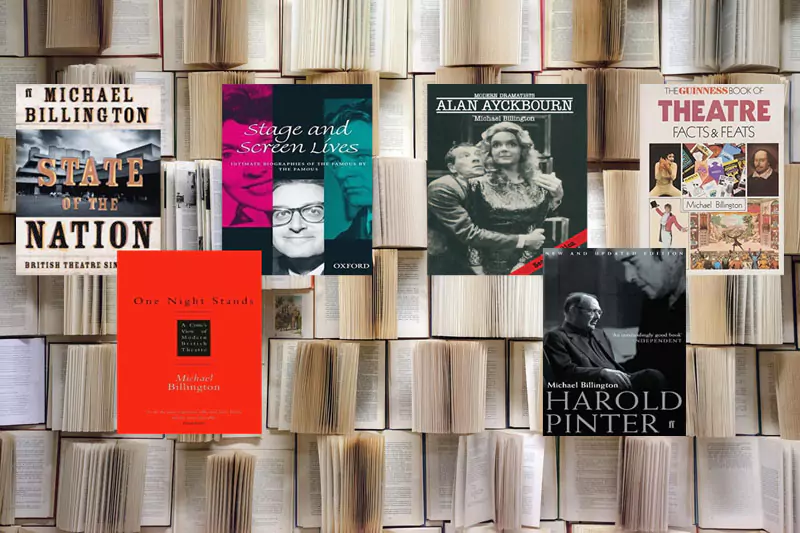

Although an interview session with Michael Billington was planned for nearly a year ago in 2019 and thus long before he announced his retirement from the post of theatre critic for the UK’s Guardian newspaper at the end of 2019, as fortune would have it our actual meeting took place in his London home in mid-January 2020. This was effectively only three weeks after he had retired, and for that reason the interview is in many ways a retrospective look at his career. The career has been a rich and varied one. Billington has been not only a critic but also an author of theatre books – most notably of State of The Nation; British Theatre Since 1945 and of the definitive biography of Harold Pinter as well as a biography of Peggy Ashcroft and studies of Tom Stoppard and Alan Ayckbourn. Earlier in his career, he has been a director and a film critic. The conversation in our hours-long interview covered many subjects in which he consistently showed rare wisdom and insight.

Michael Billington, Theatre Critic interviewed by Dana Rufolo

Becoming Michael Billington the critic

l understand you got your start as a critic writing for the very magazine l am editing now, back when it was “Plays International”.

Peter Roberts commissioned me regularly. It’s very important when you’re starting out to have someone encouraging you. It was December 1964. I remember vividly when I wrote my first piece for him. Out of that, other work followed. ln May 1965 I sent a portfolio of reviews to John Lawrence, the arts editor of The Times. He would employ as many young critics as he could. He asked if I would go to see Saint Joan in Bristol in May … l did my review on the night – in those days you had to telephone copy through – and l got back the next day and John said, “Could you possibly do The Times film column next week?” Suddenly, from being very much unemployed l was given this golden opportunity by John Lawrence. I wasn’t alone. lrving Wardle at The Times, John Peter who became The Sunday Times theatre critic, and John Russell Taylor were obviously encouraged by John.

So from “The Times” you went on to “The Guardian”, and there you stayed?

From 1965 to 1971 l was at The Times. l did theatre reviews deputizing for Irving Wardle, l did film reviews deputizing for John Russell Taylor, and then I was one of three television critics they had, and on top of that John Lawrence asked me to do a lot of film interviews. l had these extraordinary weekends, it was often the weekend when l’d go somewhere … that was a time when the American film companies were filming in Europe a lot – Twentieth Century Fox, MGM, and all that. They were all shooting in Spain or ltaly or somewhere so I’d find myself suddenly on a weekend whisked off to some lovely warm spot in Spain to meet Raquel Welch or whoever it might be. I remember one golden day in Spain when I met Raquel Welch and the next day George C. Scott …

Wow! How lucky you’ve been.

l did have a lucky time for those five years. And then in 1971 I got the call from The Guardian, and there l stayed for 48 years.

Why did you choose to leave “The Times” and go to “The Guardian”?

Because l was offered the chief theatre critic job on The Guardian, and those jobs don’t come round very often. l happened to be in the right place at the right time.

All of England is on stage: Michael Billington on British theatre today

How do you feel about British theatre, how it is evolving? Your book “The State of the Nation” looks at politics and the non-theatrical world and integrates these social forces into the theatrical world. Do you find that political issues are poisoning theatre as an artistic medium in the present more so than in the 1970s?

I don’t think poisoning, but if l was writing that book now l would again say that the theatre is a very accurate reflection of society. What I mean is this: I think what is happening in the British theatre now is that there is a huge gulf between London and the rest of the country. Not that theatre outside London is in any way inferior automatically, but there isn’t the money. All the regional theatres I know – and this applies to Scotland as well – are very much handicapped by lack of money at the moment. They’re doing fewer productions, oftentimes co-productions with commercial interests. There isn’t a single theatre outside London that has a regular company. Each theatre has to cast afresh. The RSC does [have a regular company] but that is connected to London. ln Scarborough, in the summer, Alan Ayckbourn in his old theatre tried to have a summer company, but the principle has disappeared. Whereas l grew up watching companies in regional theatres — Birmingham, Manchester. If you go to London to the theatre, you can see full houses at most theatres. Audiences are queueing up in the West End; there is a sense of affluence and economic success. If you travel out of London, theatre is handicapped, suffering from budget cuts, etcetera.

My point is that what’s happening in theatre is reflected at all times in the culture at large. People who live outside London are now regarding London with hatred. They feel they are what is left behind. And it explains a lot about the vote in the European referendum and the recent election when the Midlands and the North, traditional labour heartlands, became conservative. Because they feel they’ve missed out, they’ve been left behind, their jobs are disappearing. You’ll see a lot of boarded-up shops, pubs are closed. So l think the theatre, as so often in Britain, is a very accurate microcosm of the society, and l think there is a danger of creating theatre that is privileged in London and underprivileged out of London. lt doesn’t stop intricate productions happening; sometimes the regional productions are extremely good, but there is a growing gulf.

Yes, but l’m not just referencing that. I’m also talking about the conviction that theatre is an important medium. These economic considerations are uppermost in everyone’s minds: directors, actors, playwrights … when I see the passion with which you were reviewing plays in the 1970s, and now there is nothing that shocks or disturbs. It is always politically correct. Theatre seems to have been intimidated just as the country has been … or the economic situation is intimidating everyone?

Well, l have a slightly different take. l think you’re right about the Sixties, Seventies — when l was starting out. Yes, there was a passionate political theatre because around the world there was a sort of hunger for radical change and then disillusion when it didn’t happen post-1968. When I came to The Guardian in that wonderful period when dramatists like David Hare, Howard Brenton, all of them, were writing political plays, they were all asking the same question, “Why did it not happen? What happened to all that aspiration and optimism, why did the revolution never happen?”

We can still ask that … that is the question.

And it motivated lots of writing for that decade, the 1970s. I think now the preoccupations are different. But l think something significant again is happening. For the moment British theatre is reflecting, in a way it never has in the past, the multicultural nature of British society. That’s a big change.

I’ll give you a very concrete example of this. In the last year, the National Theatre has done three productions, one called Small Island [by Andrea Levy], based on the Windrush generation of the 1940s, then “Master Harold” … and the Boys, and the most recent production of Three Sisters which was set in the middle of the Biafran War. Those productions attracted a huge black British audience. l was there on first nights, and there were more black faces than white actually. For the first time ever. And l was told that was repeated through the run of the plays. That is a historic breakthrough. The National Theatre, while very successful, has always been accused of appealing to the conventional white middle-class audience – the “brochure audience” as someone calls it. But now in those three productions there was an extraordinary sense that the National Theatre belongs to everyone. The Young Vic is going through a similar period. It’s got a new director Kwame Kwei-Armah. The recent production they did was Death of a Salesman with a basically black cast. That again will affect the audience that will go to the Young Vic.

Photo credit: Axel Hörhager.

So you’re saying that British theatre is attracting a new audience right now?

l think British theatre at the moment is doing several things. One is it’s being consciously multicultural or appealing to a multicultural audience. Secondly, it’s addressing the big issue of the day which is gender. And again, historically the British theatre was dominated by white men. One of the first articles l ever wrote for The Guardian, in 1972, asked why there were no women dramatists. Well today you couldn’t possibly say that. You might say, “Why are there so few male dramatists?” The frontrunners for the moment in Britain are people like Lucy Kirkwood, Lucy Prebble, Caryl Churchill. It’s women who are setting the pace. But that’s also being affected by the fact that now there are more women directors running theatres.

And then there is the very basic issue of casting. You now reflect gender parity in the way you cast plays. And in classical plays it’s becoming almost de rigueur to have a 50:50 male-female split.

You have been against that. You specifically said so.

l’m sceptical about that, yes. l’m sceptical because l think the principle of broadening the range is fine, but applying quotas to a play sometimes works, sometimes not. l think Hamlet is a play you can do that with, because it works. l’m not too sure if you can do it with Julius Caesar or Coriolanus. It’s become the policy now of Shakespeare’s Globe and the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC).

All l’m saying is that the theatre is changing. There are many, many more plays now about not the big political questions but social issues. There’s an extraordinary number of plays about dementia, because that’s an issue on which society is focusing. There was a hugely successful play which is being revived now on female genital mutilation. The focus is on social and personal issues, lifestyles, even mental health.

But we haven’t abandoned plays about politics. There’s a play by James Graham who consistently writes plays that are about the here and now, he wrote a wonderful one called This House about the British parliament system, and about Rupert Murdoch [Ink]. He writes plays for television. He wrote a play about how the referendum vote was swung, so he’s like David Hare – he’s very much in tune with the times. So, l don’t think we’ve retreated entirely from politics. David Edgar is another political writer. I just think the political agenda is slightly different now. lt’s much more about how theatre reflects the actual society we live in.

Can you comment on the recent “A Day in the Death of Joe Egg”? [by Peter Nichols at Trafalgar Studios in 2019]. The actor [Storme Toolis] playing the title role actually has cerebral palsy.

That is a reflection of the fact that the subject of disability is very current. This has led to theatres casting actors who actually have a physical disability if the role requires it. Or even to cast them in roles that would not be so regarded. So, for example someone handicapped played Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire. Richard III [Teenage Dick] at the Donmar Warehouse was with an Australian actor [Daniel Monks] who has a severe physical disability. It adds weight to that play. l think we are more aware and conscious of all the big social issues and at the moment they are with mental health, disability, and dementia or Alzheimer’s. Joe Egg, as l said when it came out in 1967, was seismic in its effect. Peter Nichols’s black humour … nothing like this had ever been seen before.

Yes, but the girl was played by an actress assuming the role of a handicapped person.

Yes. Now when it is done, we are no longer shocked or surprised. It’s just one more play on the theme of handicap. Social and medical themes are the ones dominating the theatre now. My general impression is that there is more genuine diversity — in the proper meaning of that word — on stage. And more democracy, actually.

What do you mean?

l think that plays now have fewer big star parts. This is a crucial point. l think acting when l first started my job in theatre was heroic. Plays were heroic in the sense that they would often centre around a single dominant protagonist. I would say that’s quite rare these days, and plays are much more collective. You don’t get one star part; you get eight parts of equal value. Everyone has a voice. There’s a very good play at the Royal Court Theatre called A Kind of People, a stunningly good play about multi-culturalism [by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti, 2019]. There are about six characters on stage, and they all have equal value.

To me, something’s been lost in the process of having to resort to the theatre to stage social truths. But maybe you don’t feel that.

My sense of loss comes from the fact that l feel classic theatre is being neglected at the moment. There are lots of reasons. l think we’re sort of frightened of classic plays; there isn’t the range of classic plays available. l grew up in the Midlands and l could see Greek plays in the course of a season at the Birmingham Rep. If you live in that same area of Birmingham today you would not have that range of choice. In the West End when l came to live in London, there were always plays by Bernard Shaw. That is not visible now. The regional theatres are not doing classical plays. lt has mainly to do with economics. The National Theatre under Rufus Norris — it is his choice — has said, “No, our interest is not in the past”.

Of course, I can always think of exceptions when l’ve made a dogmatic statement. The best thing l’ve seen at Shakespeare’s Globe in the last 12 months was an all-women production of Richard II; the cast were made up of all black or Asian women. It sounds like a politically correct gesture, but in effect it was spellbindingly good. They spoke the language with great conviction and assurance. But classic theatre is spasmodic at the moment, though it was the staple of British theatre when I was growing up and starting to review.

Pixabay.

What other changes have you observed in British theatre during your time as critic?

In the Eighties, the era of Margaret Thatcher, theatre became all about engineering profit. You saw the rise of the musicals. Now I would say that you have writers tackling a whole range of themes and I would say experimenting with form, because there’s no consensus anymore on what constitutes a play. There was once a rough idea of what we meant by a play: it lasted for 150 minutes, you had two intervals, there was an exposition, there was a crisis. Not anymore. Also, you have different generations of playwrights co-existing. You’ve a new Tom Stoppard play – he is in his mid-eighties. Alan Bennett keeps on writing plays in his eighties. Then there is the generation of Caryl Churchill, David Hare, and you can keep going down and down. You have about four generations. The young dramatists of 17 will have their plays done at the Royal Court.

There’s a whole melting pot of dramatists. l’m giving up (criticism) at an exciting time. The theatre is reflecting more accurately than it has in my lifetime the composition of the society, and the audience itself is therefore much more catholic and diverse.

And I think that theatre does matter. Theatre will do things ahead of other media. Television is restricted by the formulaic nature of the drama; it nearly all comes in packets of the police thriller, the CIA, or the medical saga. Film as we know is a protracted business; it takes ages to set up … so by the time you’ve done the film the stakes have changed. Theatre has that capacity for rapid response. Theatre has always had that capacity, but I think at the moment we’re very conscious of that. Obviously, the big question that we’re going to have to tackle is, “Who are we in a post-Brexit world?”

Michael Billington on Continental European Theatre

During your career, you’ve flirted a bit with European theatre.

I have loved going to theatre over in Europe. My languages are terrible, but I still get huge pleasure. Some of the greatest productions I’ve seen in my lifetime have come from European directors. Giorgio Strehler leaps to mind, Ingmar Bergman, Peter Stein, Ariane Mnouchkine. Living in London one has relatively easy access to Germany and France, and I’ve enjoyed those excursions; I am at heart a European. But I think several things have happened. One is that there’s less space in newspapers these days for coverage of Europe in general.

Ten years ago, I spent a week at the Burgtheater in Vienna and I saw seven to ten productions and I would say that then they were doing productions that came from all over Europe. There was a particular production by Strehler of a Goldoni play … they were sitting on a balcony playing cards and talking in the fading light, and it was of such beauty that it has stayed with me.

There’s another production that has stayed with me. Peter Stein is a director I have always revered; he is no longer considered à la mode but I still think he is a great director … l remember he had a production of a Maxim Gorky play, Summerfolk, which he brought to the National Theatre actually [in 1977], again it has to do with the lighting and the illusion of the acting. People had had a summer picnic and they come back at the end of the day and as they moved forward from the back of the stage they moved from light into darkness; you would expect it to be the other way around. As they got closer and closer, the image got more obscure. It was an incredibly moving invocation of the end of a summer’s day, the end of an outing. So, I’ve always been haunted by the capacity of the great European directors to create durable images.

They have much more money, much more support and time, and the repertory company. But Stein is very interesting because he really did fascinate as a director. The thing about his productions was they seemed to give you access to the period in which they were set. If he used a play like Julius Caesar, he made you think you were watching a scene in the Roman Forum. I asked him, “How do you achieve that sense of appealing to our collective historical memory?” He said it’s all to do with the sound of feet on the stage.

He said, “If you’re doing a play like Julius Caesar, you have to think what would they have worn on their feet? And what sound would those Roman leather sandals they wore make on the hard marble floors?” That was extraordinary attention to detail. He was the most meticulous director l’ve ever encountered. He obviously paid attention to lighting and images but also to sound. l remember him telling me he did his first Shakespeare ever at the Schaubühne, As You Like It, and l said, “How did you prepare?” He said, “We took the whole company to Warwickshire, and we stayed there in Shakespeare country for several weeks to research the background,” and l thought, “My gosh! They could afford to do that”. Not many British directors have the money or the time to do this, but l think that’s an example of how a European theatre did have and hopefully still has a meticulous attention to detail.

At the Odéon l saw Strehler; a phenomenal production of The Tempest and a great Pierre Corneille play which I didn’t know, L’Illusion comique which is now being picked up in Britain occasionally. A man is looking for the son he has lost and he goes to some conjurer or magician who says l will bring the son to you. ln the Strehler production the father stood at the front of the stalls and on the stage we saw a recreated image of the son and where the son was and we followed the son in this adventure — it had so many different layers of reality. The payoff is that the son has died at the end of the play and the father is grief-stricken and all along the son is part of a troupe of actors and what you are watching is a theatrical recreation of his life.

Like Luigi Pirandello?

Yes, very Pirandellian. Just layer upon layer upon layer, and it was quite beautiful, a magically beautiful production. I was once invited to watch Strehler rehearsing. He was the most demonstrative director I’ve ever seen, because he would actually give actors physical gestures to imitate, he would give them vocal patterns to reproduce.

The opposite of an American director …

Absolutely. l think of a director as someone who lets the actor create … but Strehler was telling them literally. He was bouncing up on the stage every two minutes not directing them but just showing them what to do basically. The actors took this. Just on that topic, l once asked, “What is the difference between a British director and a continental one?”. He said, “lt is this: if you ask a continental actor to stand on his head, he will do it without questioning. If at the Royal Shakespeare Company I ask them that, they’d say, ‘Why, what’s the point?’” He said British actors are much more questioning and insubordinate. But British directors are now acquiring that continental idea of the director as the Supreme Being.

The Regietheater idea?

Yes. It’s not everywhere but it’s becoming more popular. One reason simply is that a lot of British directors now work a lot in continental Europe, Katie Mitchell for instance.

She works at the Odéon a lot.

She works more abroad than she does in London. Deborah Warner is another person. Robert lcke. He was at the Almeida; he’s now gone to Amsterdam. And Ivo van Hove has had a huge influence on the British theatre coming the other way.

l spoke to a young British director about this a couple of months ago. He said, “There’s one very good reason why we directors want to work in Europe. . . money.” lt’s very hard for British directors to earn a decent living in Britain, unless you’re a superstar. The only way to survive economically is to go and work in Germany or in France or wherever — he said he would probably be paid three times as much in the rest of Europe as he would in London. So, it is the economics which is driving as much as it is the inspiration of European directors.

Michael Billington and his friendship with Harold Pinter

Your real job is working as a critic, but your second job is as an author of books.

Yes.

And I’m interested. Could we just talk a little bit about the Harold Pinter book (Harold Pinter, first published by Faber and Faber in 1996)? I fail to understand the charisma that Harold Pinter had with people; what is it? From the British male I suppose more than the women, l don’t know because l have never heard a female reaction. Why did Harold Pinter have this charisma, as a person, not just as a playwright?

l think the two things are inseparable, l think we all were a generation — several generations now — who were galvanized by Harold Pinter’s plays. We grew up watching Pinter’s plays from the earliest plays … The Birthday Party, seeing him progress and become a celebrated international playwright. And I think the work itself taps into people’s fears, insecurities, nightmares — the feeling that we’re all on the edge of an abyss. That’s what Harold is really saying in all of his plays, you know. That’s the essence of The Birthday Party … if a knock came on the door now, l would not know who it is, it might be the postman … it might be someone who’s come to fetch me for something, you know. We all have that buried fear l think, so that’s one aspect of his charisma.

l would say that everyone who knew Harold – actors, directors, people who worked in the theatre – were very moved and distressed by his death, and even today people who worked with him will talk about him endlessly. And you said earlier that you thought it was men who liked him; l would say it was women equally because Harold had a genuine love of women. He said he adored female company. l think he’d rather talk to women than men actually. But he could talk to men about cricket or whatever you wanted. He talked to women about other subjects. In some ways he had the solitude of the only child. But at the same time, he loved – he was – the centre of attention. Women, girls flocked to him in a way they didn’t to his contemporaries, I gather. But he was actually loved by people who got to know him very well because as l’ve said there was this feeling of mutual loyalty. Unless of course he felt that you had betrayed him.

Betrayal.

Exactly. He fell out with Peter Hall as I am sure you know, because he felt Hall in his diaries had revealed too much about Harold’s private life, and for several years they didn’t speak. ln the end, they actually came back together again. So, Harold inspired loyalty but also l think demanded it as well which is fair enough.

He never sat down to write a commission; he never sat down at nine in the morning and said, “l am writing today.” He would wait for the moment, the idea, the word, the image to come and that would trigger his imagination, so he lived in that strange state of waiting for inspiration to come.

You felt that as a writer yourself, or was it something he allowed you to become privy to – his creative process?

Well yes, this is the strange thing. Harold Pinter and l had rather a fractious relationship for a period. l didn’t like some of his plays. And then one day l got a letter at The Guardian. The publisher Faber saying would l like to discuss doing a book about Harold Pinter’s politics with Harold Pinter – we’d have a lunch. So the three of us met for lunch. What was meant to be a book about politics turns into an invitation to write the life … Harold said, “You can talk to anyone you like, come read all my letters, documents, whatever.” l was open-mouthed.

What he talked about to me was the origin of all his plays. We went through all the plays one by one, and each time he’d reveal the source and that to me was like gold.

A few critics, particularly Martin Esslin who was a great scholar, were outraged. When he reviewed the book, he thought that l had somehow diminished Harold by making it seem as if he was simply using his life. And in my defence, of course he wasn’t simply transposing his life but plays have to start somewhere. With Harold they started with a memory of something that had happened to him often some years ago, and he was telling me what those somethings were.

Did you feel that the menace that you yourself admit one feels in Pinter’s plays has to do with him being evacuated during the war?

l don’t think that was the real origin. I think it has much more to do with growing up in the East End of London in the war … in an atmosphere of danger. l think also you can’t neglect that he was an only child, he read voraciously … that fed into his imagination as well.

So he didn’t go back into a pre-conscious childhood …?

Who knows? One thing l remember him telling me. I said, “What was your childhood like?” and he said, “We had a very pleasant garden and there was a big tree in the garden and l would sit under the tree at the age of seven or eight or whatever and invent stories. Because he was an only child, he’d invent imaginary companions. If that isn’t the birth of a playwright, then what is?

But that sounds very much like you yourself.

If you’re an only child, which I was, growing up in the war … very much like Harold Pinter…

So did you sit under a tree and make up stories?

Psychologically, l wanted to escape. An only child from a very modest background, working-class background really, you want to escape into other worlds of fantasy, so books was one (world). Films was another big escape for me – and theatre. I was helped by the fact that my father really liked the theatre. He couldn’t afford to go very often, but we would go. At the age of eight l went on a family outing to see Troilus and Cressida at Stratford with Paul Scofield in the cast [Shakespeare Festival 1948]. l didn’t know then he was Paul Scofield, but the play registered very strongly with me. Language, colour, the excitement of it: the theatre seemed incredibly glamourous.

So that childhood experience is what got you started as a theatre critic?

Also, when I was at Oxford I acted in plays and I directed plays. I thought, “Well maybe directing is the thing?”. But I was also at the same time being asked to review plays at the university newspaper called CherweII. When I sat behind a desk writing a review, I felt comfortable, I felt at ease with myself. And I thought, “Obviously if I’m at ease reviewing, that’s maybe what I should strive for.”