“Machinal” at Theatre Royal Bath’s Ustinov Studio

Simon Thomas in the South West

1 November 2023

Deborah Warner’s tenure as artistic director of Bath’s Ustinov Studio continues with a blistering production of Sophie Treadwell’s Machinal, directed by Richard Jones. Like Warner, Jones is one of the finest directors of plays and operas working in the UK at the moment and the match between him and Treadwell’s 1928 expressionist play looks perfect on paper. In reality, it proves just that, with Jones’s unique style turning a demanding, and at times baffling, text into theatrical gold.

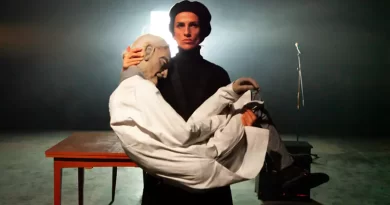

Wendy Nottingham and Tim Frances.

Photo credit: Foteini Christofilopoulou.

It’s an exhausting evening, as the tension is ratcheted up scene by scene and explodes in a devastating and shocking finale. As one would expect from Jones, the ensemble playing is impeccable but much of the power of the drama is driven by a riveting central performance by Rosie Sheehy.

She begins the play at a high pitch, resembling over-wound clockwork, and manages somehow to keep raising the stakes, until her character reaches a point of complete implosion. The force of her spat-out stream-of-consciousness monologues is breathtaking and frightening. One can only imagine how the actor feels at the end of this intense hour and fifty minutes, mining the depths of the human condition for all she’s worth.

The play’s title Machinal has layers of meaning, which includes the mechanistic demands of modern society on the individual, the electric chair that finally destroys her, and, as played by Sheehy, the Young Woman herself, who has somehow been turned into an engineered shell of a human whose only course is to break down in spectacular fashion. It’s Chaplin’s Modern Times meets Kafka meets Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

Treadwell (1885–1970) progressed from being a newspaper reporter to write at least 39 plays and a number of novels, with Machinal her most famous work. The play premiered in New York in 1928 (starring one Clark Gable as the lover, in his Broadway debut) and then fell into obscurity until the last few decades, during which time it has been revived a number of times. Fiona Shaw played the leading role at the National Theatre, directed by Stephen Daldry, in 1993/4.

Rosie Sheehy and cast.

Photo credit: Foteini Christofilopoulou.

One of the cases Treadwell covered as a journalist was that of Ruth Brown Snyder and her lover Henry Judd Gray, who both went to the electric chair in 1928 for the murder of her husband. For English audiences, the case has resonances with that of Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hung in England, which helped bring about the abolition of the death penalty.

Treadwell’s angle is a feminist one, with her protagonist ground down by an oppressive society and the demands of overbearing men. Escape is a major theme, with the Young Woman (later named as Helen Jones) finding release from the energy-sapping daily routine of sweaty commuting to a soul-destroying menial job, by marrying the boss, which is followed by sexual pestering and the traumatic birth of a child.

At no point does she have illusions; as she jumps from frying pan to fire, she’s only too aware of the harrowing consequences of a reality that is slowly grinding her down. In marrying a much older man she doesn’t love, she knows it’s replacing one nightmare with another. “She’s got that gagging – like she had the last time I was here,” says her husband on a hospital visit.

Treadwell’s text is sparse, tense, disjointed, way ahead of its time, sounding like David Mamet’s broken speech patterns and Tennessee Williams in its more naturalistic moments. She deals with topics that would not have made it through the film industry’s forthcoming Hays Code: sexual suggestiveness, prohibited drinking, abortion, and hints of homosexuality.

Whatever designer Richard Jones works with (here it is Hyemi Shin), all his stagings look like a Richard Jones production. That’s not to say they’re all the same; rather he has a consistent house style, which in this case fits the material to perfection. He squeezes his 12 actors into a small room with receding walls that takes up only half of the Studio’s already confined area, creating a claustrophobic space with angles all off-kilter. His use of captions, setting each of the nine episodic sections of the play or episodes, is characteristically imaginative, sometimes casting eerie shadows on to the walls.

Another aspect that is emphasized in the script and, again, superbly executed here (sound design Benjamin Grant) is the soundtrack of offstage noise: voices, mechanical sounds, drilling, aeroplanes, bands. These build up a background of constant hubbub, oppressing and torturous. The image of a caged black man singing a song of freedom, as a priest intones Latin and the moment of execution draws near, is both moving and disturbing.

Of the supporting cast, Tim Frances as the husband and Buffy Davis as the woman’s mother stand out due to the prominence of the roles but this is a tightly drilled ensemble without weak links, whose laser-like precision adds to the mechanistic quality of Treadwell’s nightmarish world.