Loudon Sainthill: A Retrospective

Loudon Sainthill (1918-1969) was an Australian artist and designer who worked in London from 1949 to 1969. He designed both sets and costumes for the theatre, and his paintings were regularly exhibited in a number of commercial galleries in Australia and the UK. After permanently relocating to London in 1949, he collaborated with renowned directors including John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier and Noël Coward at theatres such as London’s Haymarket, the Savoy and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.

Kathleen Ashby, Assistant Curator at Arts Centre Melbourne when she wrote this article introduces the gifted designer to a modern readership through an analysis of a suite of Sainthill’s costume designs recently acquired by the Australian Performing Arts Collection. Ashby graduated with a Master of Art Curatorship from the University of Melbourne in 2015 and currently works at The Johnston Collection, a museum of fine and decorative art located in East Melbourne.

Kathleen Ashby on the Australian theatre designer Loudon Sainthill

In 1948 Loudon Sainthill lamented to a journalist from Sydney newspaper The Sun that there were “no opportunities for a designer in Australia” and this was why he would be going abroad in a few months’ time. During the previous decade, Sainthill had worked to establish himself as an artist and costume and décor designer in Sydney and Melbourne. At the time, hardly any visual artists designing for Australian theatre productions were well paid, and even fewer secured long-term residencies in theatres. In his biography of Sainthill, art historian Andrew Montana wrote: “… it was creating décor and costumes for the stage that drove Sainthill. And he was prepared to go unpaid. His success in London was a testimony to his enduring enthusiasm that he first demonstrated in Australia for this work.”

Loudon Sainthill (1918-1969) was born in Hobart on the Australian island of Tasmania; his family moved to Melbourne when he was a child. His choice of career came about because he was inspired by the Australian tours of Colonel de Basil’s Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo in 1936-7 and 1938-39. An exhibition of his paintings featuring the dancers and sets led to an invitation to travel to London with the company in 1939. Later that year Sainthill returned to Australia in charge of a major exhibition of theatre and ballet designs which toured the country coinciding with the ballet season.

Opportunities for independent designers in Australia in the 1940s were limited, and during his early career, Sainthill was one of a number of Australian artists who struggled to make a living from designing for the stage. The dominant theatrical production company at the time was J C Williamson Theatres Ltd, but costume and scenery designs were in most cases acquired contractually with shows purchased from the United Kingdom or the United States of America? These designs were then realized by local contracted scenic artists and wardrobe staff.

Sainthill and his business and life partner Harry Tatlock Miller were active supporters of the plan for a large performing arts centre in Melbourne, which arose around the time of the separation of the National Gallery of Victoria and Museum and State Library boards in 1945. During the initial stages, Wirth’s Park had been selected as a site for the venue, but sadly Sainthill would not live to see it realized.

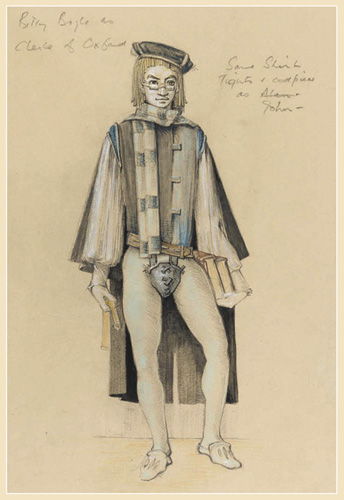

Clerk of Oxford costume, Canterbury Tales (1967)

The plan to move permanently to London came to fruition in 1949, and Sainthill was soon regarded as “one of Australia’s greatest cultural exports.” His name regularly appeared alongside opera singer Joan Sutherland and ballet dancer Robert Helpmann in Australian newspaper articles reporting on the triumph of creative expatriates working in London in the 1950s. At the height of Sainthill’s success in England, his designs were brought back to Australia when the Old Vic Theatre Company toured Shakespearean plays in 1955 and 1961. Sainthill was the only Australian designer employed by the company for the tours; the other two were British. His designs for The Merchant of Venice starring Katharine Hepburn, demonstrated his penchant for medieval imagery and settings – a recurring theme throughout Sainthill’s career. Other key designs inspired by the late middle ages included his Henry V pavilion, which was the highly anticipated home for the flower decoration display at the 1947 Red Cross Chelsea Flower Show in Sydney, and his costumes for Sir John Gielgud’s production of Richard II in 1952 and Canterbury Tales in 1968. Sainthill’s references to a medieval aesthetic in his designs were not strictly historically accurate and his motifs transcend specific eras, but these productions nevertheless have similarities in their design focus.

Sainthill’s elaborate style was immensely popular in the 1950s, but by the 1960s it was sometimes criticized by theatre practitioners who advocated a more minimal aesthetic. This was part of a wider shift in direction for theatre, with productions taking a more stripped-back approach to staging and costumes rather than creating a sense of grand illusion. The enduring popularity of Bertolt Brecht’s “Epic Theatre” movement which emerged in the 1920s, and the arrival of Jerzy Grotowski’s “Poor Theatre” concepts on western stages in 1968 inspired such changes in approach. By this time though, Sainthill was well established in the London theatre scene; his designs were greatly in demand. Michael Benthall, who produced the 1951 Shakespeare Memorial Theatre production of The Tempest for which Sainthill designed the sets and costumes, described him as “the hardest working artist and one of the most talented I’ve ever known.”

Queen’s costume, Canterbury Tales (1967)

Arts Centre Melbourne, as custodian of the Australian Performing Arts Collection (APAC), recently acquired a rare portfolio of costume designs by Sainthill from the Australian production of Canterbury Tales which toured nationally in 1969 and 1970. The acquisition comprises 36 costume designs along with a folder containing annotated copies of the designs, fabric swatches, and theatre programs for the production. Canterbury Tales was a musical based on Nevill Coghill’s modern English version of Geoffrey Chaucer’s late-fourteenth century collection of 24 stories, The Canterbury Tales. The work was conceived, directed, and written by Martin Starkie with Nevill Coghill as co-writer. lt was presented at the Phoenix Theatre, London on 21 March 1968 and was one of the last productions Sainthill worked on before his untimely death at the age of 52 on 9th June 1969. The London production was very popular with audiences and ran for two 2,080 performances. The musical then transferred to New York in 1969, although it was limited to only 121 performances due to exorbitant production costs. Shortly before his death, Sainthill won the 1969 Tony Award for Best Costume Design for this Broadway version.

The Australian production opened at the Theatre Royal in Sydney on 17 May 1969, then traveled to the Comedy Theatre in Melbourne, His Majesty’s Theatre in Perth in 1970, and then back to Sydney and Melbourne. Sammy Dallas Bayes directed and choreographed the Australian production and was nominated for a Tony Award for his choreographic work on the Broadway production. Canterbury Tales focused on four tales from Chaucer’s work: The Miller’s Tale, The Steward’s Tale, The Merchant’s Tale, and The Wife of Bath’s Tale. The suite of designs acquired by the APAC represents the majority of the central pilgrim characters who narrate the tales and a selection of other characters.

Sainthill designed many of the costumes, especially for the Australian production. Other designs are labeled with the names of actors who performed in the London production, suggesting that these designs were created for the original production or they were rendered from those original costumes and used as a reference for the Australian wardrobe team. Some of the designs within the collection are highly finished and the intended final costume is easy to determine, while others are less detailed sketches, suggesting a silhouette without specific details about fabric and finishes.

Sainthill’s designs for both the London and Australian productions of Canterbury Tales were rendered in pencil, pastel, and gouache on coloured cards. These cards created a reference point for Sainthill to work in relation to the colours used in Derek Cousins’ set designs. This demonstrates Sainthill’s creative process and the way in which he considered the overall effect of his costumes as part of the larger production.

King’s costume, Canterbury Tales (1967)

A black display folder, acquired along with the costume designs, contains notes and fabric swatches for each costume, providing a wealth of detail regarding the design and construction process. Often these notes include references to the fabrics used in London and in New York. These notes also outline where an actor plays more than one character. For example, the design for the Prioress notes “Actress No 2 Prioress. Also plays Proserpina and Queen Guinevere”. The collection has been supplied with fabric swatches for the Prioress’ cloak and robe from the earlier productions, along with a sample of the veil fabric. ln cases where major changes have been made from previous designs, this has been noted. For example, designs for the Cook include the notation: “This costume was simplified for reasons of economy – the leather decoration was omitted and strings of artificial onions were hung over the shoulder”. This demonstrates that not all the designs for the Australian production were copies of the original designs for the London production. Rather, revisions were made by Sainthill with the budget for the Australian production in mind.

This folio of designs and supporting material document a key production in the career of one of Australia’s most important twentieth-century stage and costume designers. Now held for posterity, this significant acquisition was made possible by the generosity of theatre producer Malcolm C. Cooke and the David Richards Gift which provides financial support for the development and care of the Australian Performing Arts Collection’s design collection.