“La Clemenza di Tito”, Opera Ghent, directed by Milo Rau

Dana Rufolo in Ghent

October 2023

The first foray into directing opera of the acclaimed Swiss theatre director Milo Rau with La Clemenza di Tito, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s last opera, is a disturbing triumph and a glorious failure. Which is fitting, in that the filaments running through his complicated and often chaotic mise-en-scène are themselves starkly oppositional.

The refugee camp.

Photo credit: Annemie Augustijns.

It was the time of the pandemic when the opera premiered as a Zoom production at the Théâtre de Genève. As a live production, it recently travelled to Flanders, first in Antwerp at the Opera Ballet Vlaanderen and then in Ghent at the Opera House, which is where I saw it on 6 October. After Belgium, the opera will visit the Grand Théâtre in Luxembourg on 24 and 26 October and then will be staged in May 2024 as the opening piece of the Vienna’s Wiener Festwochen (Vienna Festival Weeks), of which Milo Rau is the new artistic director.

Using a revolving stage to portray two contrasting sets – one suggestive of wealth and ease and the other of poverty and suffering – on the old-fashioned proscenium stage of the Ghent Opera House is a clever move in that the dynamic of changing scenes overcomes the static limitation of an elevated rectangular stage space. The orchestra is hidden in a pit in front of the stage.

What is almost by now a signature aspect of Rau’s work is the porousness of his stage. It is not a protecting, self-sufficient and extraterritorial space on which magical events transpire that permit the audience to dream a little, but rather the external world impinges on the theatrical drama and reduces its capacity to seduce. In the case of La Clemenza di Tito, the libretto’s original clear themes of love, jealousy, and benevolence are fractured and compromised.

Maria Warenburg (Annio) and Sarah Jang (Servilia) attack Jeremy Ovenden (Tito).

Photo credit: Annemie Augustijns.

Before continuing with my analysis of this complex production, I’d like to turn my readers’ attention to the history of the opera itself. Mozart composed it for the coronation in Prague of the Hapsburg, Leopold II, as King of Bohemia, and the reference to Emperor Titus known for his clemency was intended to be a reminder of “clementia austriaca”, the benevolence associated with the Hapsburg line of rulers. Since the French Revolution had begun two years earlier, there was an urgent need for the ruling class to be reminded that greatness calls for clemency.

Rau is motivated to describe both sides in this opera: the dominant ruling class and the people who are ruled and wish to be free.

The stage set representative of wealth, tranquillity and order is where the emperor Tito lives; it has the look of an atelier and art gallery with the diffuse overhead lighting on its roof reminiscent of the ceiling of modern art museums like the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels; large artworks and photographs adorn the walls. It is the set used in the opening scene where the 18 non-professional actors Rau engaged and the cast of professional singers and actors move around drinking champagne from fluted glasses and talking or studying the works of art on display, as happens in Vernissages. It is where art, having been extracted from the reality experienced by the powerful of this world, is created and then displayed as a rarified form of the real. This is the space in which contemporary powerful people equivalent to Leopold II continue to thrive.

Just on the other side, however, half a revolve away, the set in shades of brown (designer Anton Lukas) is a camp of tents and shacks for refugees – initially those who had to flee the lava flows of Vesuvius in the eruption of 1774, three years after La Clemenza di Tito premiered but soon morphing into a present-day homeless camp which is even suggested to be an encampment in front of the Capital à la January 6, 2021. In this set, reality is survival. In so far as art exists in this reverse space, it is imposed by Rau in the form of documentary film-making. He also uses masking techniques where faces and hands are decorated by blood or by artificial blood or by mud. It is a “primitive” world, where a shaman thrives and mystical substances drug the sensibilities or – as happens to Tito, who is in fact stabbed to apparent death by Sesto (the murder is not a mistaken identity in this untraditional interpretation) – bring people back from the dead.

Art has its scenic parallel – see above photo. History mellowed into

art in this painting by Artemisia Gentileschi displayed in Tito’s opulent

residence. Photo credit: Annemie Augustijns.

About the use of film on stage: in this set which focuses on people who are deprived, Rau employs the relatively new technique of having cameramen (headed by Laurent Fontaine-Czaczes) enter on occasion and film faces or actions up close. The images are projected onto a screen suspended over the middle of the stage which has printed on it in blood-red block letters the words “Kunst ist Macht” (“Art is Power”). The characters address or sing to the faces projected on the screen rather than to the actor standing there whose face is being projected. This technique is used almost to excess, particularly in Act Two, but also it is distinguished as an experimental technique that reveals how all of us have psychologically integrated digital media into our notion of presence and body to the point where a film of a face is equivalent to bodily presence.

Along this same line, one of the most telling scenes in the opera is when a riot takes place during Act Two among the homeless on this side of the revolve: at one moment, a fellow with a mobile camera films the action as guards lightly restrain protestors; he is curved backwards as if to isolate himself as much as possible from the scene, and he obsessively peers into his phone screen, recording the truth as the eye sees it. We know he will turn the film into a viral cry of outrage even though in those moments he was utterly disengaged from the physicality of the people in front of him and their needs.

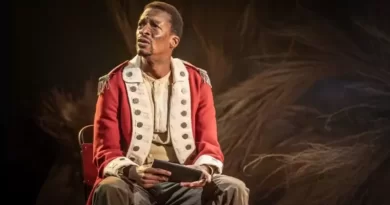

It is an anti-opera opera in Rau’s hands, and this is where the element of glorious failure is rooted. Rau feels too guilty about what he thinks it would mean if he were to have yielded to the integrity of the story with its power elite perspective. Everything has been toned down to keep Rau in command – the orchestra under the baton of Alejo Pérez plays liltingly but softly, not once distracting from the visual images that are contradictions to Mozart’s sweetness and the extraordinarily fluted soprano voices surrounding him. Exceptions are Titus (Jeremy Ovenden) who is a rich tenor, and the extraordinary Anna Goryachova who plays Sesto as a mezzo-soprano. Publio (Eugene Richards III) is the only bass.

The opening scene in Tito’s residence. Set design by Anton Lukas.

Photo credit: Annemie Augustijns.

One has to remember that Mozart wrote at a time when castrati were used in opera, and castrati sang in the original La Clemenza di Tito. The mezzo-soprano required for Sesto’s arias means that nowadays women sing the part of the male friend of Tito who betrays him with a stab, in cross-dress. The high number of sopranos in this opera is a fact on which La Clemenza di Tito directed by Martin Kušej that played in 2003 at the Salzburg festival, with its gender reversals and lesbian pairings, played. Rau makes much less of this.

The inexorable erasure of local culture is an umbrella theme in Rau’s passionate desire to show not only the beautiful real and its arias and delights but also the underbelly of pulsating vitality spawn of misery that sustains it. In the opening scene, in front of the Vernissage guests, a man undresses to his underwear and reports that he sometimes feels like he is the last Flemish man in Flanders when he looks around him (at the refugees and new arrivals) – he is not racist but simply stating an observation. Before we know it, he is on the ground and his heart is cut out of his chest. That heart (made from silicone we are neatly informed later on in the opera so as to make sure that we don’t entertain false illusions) is passed around from singer to singer like a signal or a message.

As we hear breathtaking arias and dramatic coloratura from the likes of Servilia (Sarah Yang) singing “S’altro che lagrime” or Vitellia (Anna Malesza-Kutny) singing “Non più di Fiori”, surtitles in Flemish and English do not translate the lyrics but rather tell us about the 18 untrained extras that were hired to be part of the cast – chiefly immigrants coming from Belgium Congo, Syria, the Philippines … a mother and her daughter. We hear their names, we learn about their immigration history and their families, their aspirations and we see projected photos of their abodes. These are the people with their feet on the ground, Rau is telling us; these are the people who live here in Ghent or in the nearby Flemish city of Antwerp. We can no longer sustain separation; walls collapse, oceans are not barriers. The European world is transforming into a melting pot before our eyes.

The final image left us is very sad. We are told to imagine an earth – at least our western part of it – empty of people and gifted with the occasional burst of bird song. The heart has been ripped out of this opera famously known for its love intrigues and for Vitellia’s act of revenge against Tito for having passed her over as his future wife. When she sends her lover Sesto to set the city on fire and murder Tito, which he does, she destroys her own future, for Tito has indeed selected Vitellia to be empress. All that is left to hope for is Tito’s clemency, which is shown, for he has returned to life in order to perform his noble deed through the benefit of magic potions that come not from the elitist rich world but from the peopled poor world. And this is the world that is winning – one unable to sustain arias and recitative, disintegrating into silence.

This closure seems to have spoken directly to the audience. They had applauded sparsely after Act One, but at the end of Act Two of they rose en masse to give it a standing ovation. The limpid-voiced actor-singer playing Sesto – Anna Goryachova – was the most appreciated of all.

As a footnote, I’d like to add that in Rau’s just published book Die Rückeroberung der Zukunft (Reclaiming the Future), he openly describes the aesthetic of resistance that he has used in this Regietheater production, indicating his long-term artistic position: “We engaged artists have the purpose to shock our public into understanding that what is accepted as normality is indeed the fake harmony of those who rule.” («Es geht darum, zu skandalisieren, was als Normalität behauptet oder hingenommen wird, die herrschende Harmonie zu entlarven als falsche Harmonie der Herrschenden.»)