“Faith Healer” at Lyric Hammersmith

Jeremy Malies in West London

28 March 2024

“I always knew when nothing was going to happen.” Frank Hardy, the title character in Faith Healer (played by Declan Conlon), tells us that he knew when the gift would not be upon him and the magic would not ignite to cure the sick at the seedy halls across Scotland and Wales where his cockney agent Teddy (Nick Holder) had booked him.

Justine Mitchell as Grace.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

It might be hubris but I too believe I can now sense whether the mesmerism of Brian Friel’s incantatory language in this set of four interconnected monologues will take wing or remain earthbound. I trust myself early on to know when there will be exaltation and consummation. As Conlon speaks of how elusive his curative powers can be, I realize that director Rachel O’Riordan is about to mainline us with an authentic experience.

This is a play about the unreliability of memory, how even well-meaning witnesses to both the ordinary and the sublime can be mistaken as they subconsciously meet their own emotional needs. The monologists (Friel’s own word) are Frank, Teddy, and Frank’s lover Grace played by Justine Mitchell. The first and last monologues are from Frank while the second and third are spoken by Grace and Teddy respectively.

Conlon is the most self-aware and self-analytical Frank I have seen. Stage directions ask for him to be predominantly still, and the few movements and gestures all count. For much of the time, his hands remain in the pockets of the coat and suit that he obviously sleeps in while on the road in a battered van. Such are the performers’ ability to mimic each other that the individual acts become fully peopled plays in the manner of an Alan Bennett “Talking Head”.

The title role may be the coveted one (James Mason took it in the 1979 New York world premiere and it has also been played by Ralph Fiennes) but good judges often see Teddy’s as the more interesting speech. Here, Holder (an impressive would-be murderer of Richard Nixon in Assassins at Chichester) is outstanding as he conveys the character’s satisfaction at having been involved as an acolyte in something spiritual if not religious. Teddy makes a point of addressing the audience, and Holder judges the auditorium perfectly as he sustains gales of laughter while describing the bizarre animal acts his character has managed in the past.

Nick Holder as Teddy.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Mitchell by contrast is forensic in documenting a breakdown that resembles a trance. Orderly and disciplined while she and Frank were on the road, she too is now an alcoholic and about to take a drug overdose. There are achingly sharp recollections of snatched happiness amid all the squalor, walks in the Grampian hills or the few hours of triumph before her lover surrenders to his sad beautiful deathwish at the hands of farmers in Ballybeg, the fictional Donegal town in which Friel set so many of his plays.

Directors at theatres with more flexible configurations often choose to have a few seats on an angle such that we envisage ourselves as having shuffled into one of the kirks at which Frank performs. O’Riordan does not have this option but, with lighting designer Paul Keogan, she hints at the stained glass of whatever church Frank’s ghost now inhabits. Conlon shows his character’s relish for the religious language he uses to describe the healing but he always admits that it is nothing more than a craft, perhaps autosuggestion and with a hint of quackery.

O’Riordan brings all the actors through the thickets of Friel’s imagery, the litanies of place names which could easily become tedious, and the pervading fatalism. There is an ethereal quality to the production which reminds us that the characters are before us only as spirits. This is a memory play but there is no all-seeing narrator. And of course the memories conflict, with the most obvious discrepancy being Grace’s background. Frank sees her as being from Yorkshire when (as the most reliable witness) she tells us that she is from almost the exact shabby-genteel Irish legal family that Friel creates in Aristocrats.

Others may find parallels and messages, but I believe that (unusually for Friel) the play is apolitical. There is, however, the trademark obsession with place names that characterizes Translations. In terms of structure, the play is not totally cohesive with “Where had we got to?” being inserted a few times as characters break for asides before hurtling towards descriptions of deaths. Only Teddy, though surely a ghost, does not disclose how he has died.

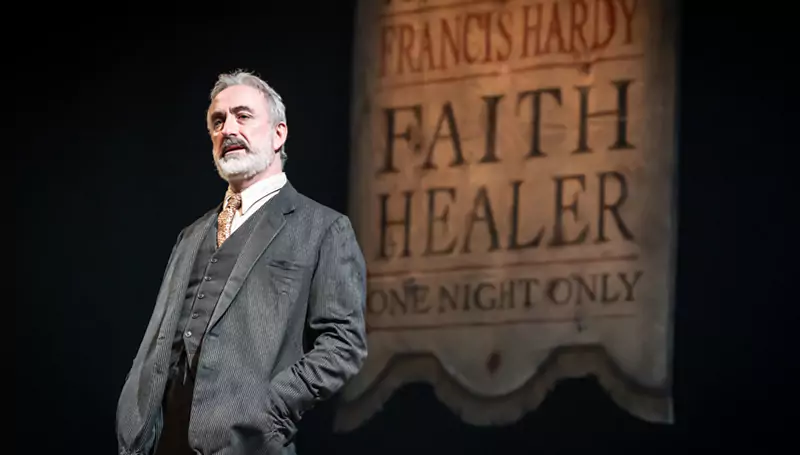

At a less modernist exterior than the Lyric, the totemic somewhat shabby poster that dominates the design (by Colin Richmond) can also appear in the foyer:

“The Fantastic Francis Hardy

Faith Healer

One Night Only”

O’Riordan is right to limit the design so that we know that these scenes are imaginings. The set is little more than a diorama of the countryside loam that makes up the primitive roads the trio must drive across and into which Grace must bury her stillborn child. But it’s enough to make us have a sense of the wretched smells that haunt Teddy – damp straw in barns, a camp primus stove, and nights sleeping in cow fields.

“We were always balanced somewhere between the absurd and the momentous” is Frank’s most telling judgement. This wonderful production sits in that hinterland. Fortunately not one night only! Faith Healer runs until 13 April.