Enda Walsh talks about his plays at Almada Festival, Portugal

The following text is the transcript of a talk that Enda Walsh gave on 11 July 2024 in the context of his play Medicine, playing in Portuguese with the title Remédio, which was performed three times during the Almada Theatre Festival. Walsh, an Irish playwright who came to prominence in 1997 with his play Disco Pigs, writes film and television scripts and operas as well as plays. His plays are popular in Portugal, and the director of Remédio explains why in the question and answer section of the transcribed talk below.

Enda Walsh gave his talk on the esplanade that stretches from the Joaquim Benite Municipal Theatre to the outdoor performance space of the Escola D. António da Costa which is run by the theatre and its permanent staff. The following transcription of Walsh’s talk includes questions asked by the audience and comments from members of the panel that comprised: Enda Walsh; the translator of the play Joana Frazão; João Carneiro who is a Portuguese author and theatre critic writing for the weekly national newspaper Expresso; and the director of Rémedio, António Simão.

Dana Rufolo

11 July 2024

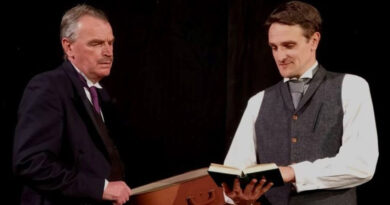

Joana Frazão, Enda Walsh, journalist João Carneiro, and Rémedio‘s director António Simão.

Photo credit: Axel Hörhager

Enda Walsh [EW]: I’m sorry for speaking in English. It’s Irish English, so hopefully it will be clearer. I’ll try to speak slowly, which is difficult for an Irish person!

I don’t know how Medicine is different from the other plays of mine. It came from my father who was a furniture salesman, and he had his own furniture shop. He was an amazing mimic; he could do impersonations of people and he could change character. As a little boy I had a stammer, I couldn’t talk properly so he was my hero. My first introduction to theatre was watching him on the shop floor changing shape and being incredibly suave. As a boy who couldn’t talk properly, I found that intoxicating. So, the characters in a lot of my plays tend to do that. I think that in Medicine there is a similarity to earlier plays – a lot of my plays tend to shape-shift.

I write plays about the inarticulate, obviously because I couldn’t talk when I was a kid and it takes me a thousand words to say three words properly.

There’s a relationship in this play with the character, the poor guy who is stuck in an institution and is trying to find the right words to explain himself to himself and having people around him explain his story to him and control him through story. Or to steal his story, and his ‘self’, and try and manipulate it for their own entertainment. The reason I ended up writing it is that my mother had Alzheimer’s and I was watching her in care; she was a very flamboyant woman but like everyone with Alzheimer’s she became furniture over time She became like just a chair and it was brutal to watch that happen. And the carers … they were looking after her but they were imposing an idea of her on her without her having a say, and I found that incredibly devastating. It’s sad and miserable. But melancholy and high comedy sit really really easily in the Irish psyche – we’re fine with that, we like the flip of those things. And I think this play investigates that, it deals with the tragic life of this person but at times it’s done in such a cruel way and for our entertainment, so it becomes uncomfortable I think.

I don’t analyze my work like many writers do. I think about it in very abstract terms. Sometimes it’s a feeling. A contemporary writer who’d been a friend of mine called Sarah Kane was, from those of my generation, the one who was pushing the work more than the rest of us. I asked her what she was planning, and she answered, “Well I haven’t started writing it, but I can hum it!” I think that’s what plays are. You can feel it a lot of the time and you begin writing it and then you find echoes, and you say, “Oh my God! I’m writing about my mother” or “I’m writing about myself” or “I’m writing about Ireland’s treatment of people who are in asylums and mental institutions for decades, like many countries”, so I ended up writing about that, but it was like everything a complete surprise for me that I was writing it.

Question from the audience: I recall a scene in a play of yours where you talk about the green of the trees, the light of the sun, the fields. I think it makes a kind of punk-pastoral kind of play. Do you agree?

EW: It’s true. The character in Medicine has been incarcerated since he was 18 or something like that. A lot of the characters I write tend to be still girls or still boys; they are sort of stuck in a time. Ghosts. You know, we all feel that a lot of the time. I think you’re right. There’s a great naivety in talking about nature; when you use a metaphor like that in a play that’s dark … A character tries to reach for something so naïve but simple and pure, and it brings you back to the moment when you’re seven or eight, that feeling.

Question from the audience: You directed Medicine. Do you usually direct your plays?

EW: Yes, all of them. I think about a play for maybe three years, and then I write it very fast. So all the plays take about three weeks to write. And then I just tell the producer I’ve just written this play, and they book the theatre, and I hire the actors, but I don’t read the play. I talk to the designer and the designer designs it, and I come in on day one and I open up the play and I experience it. It’s very fresh. Also, I don’t understand the logic of Enda Walsh the writer. I’m going, “Why is he doing this?” and “Why is he doing that?” and the actors are looking at me and going, “Do you not know your own play?” And I say, “I do”, but when you’re writing a play on instinct and you’re very far away from your instinct, like a year later or eight months later, you are a completely different you, and also you’re trying to experience and learn these characters fresh again, so you’re trying to remember again why you wrote it and what they’re trying to do. So, that’s enough for me and I blindly go at it, but I know that I will go back to my initial instinct of day one and having a blank page. I’ll find that again, but it takes a long process to go back to that.

Translator Joana Frazão: This is the eighth play by Enda that I’ve translated so I’m kind of used to his universe. They speak their own version of what they were hearing in court.

Journalist João Carneiro: I’d like to talk about Enda’s plays called Rooms. A hotel room, etc. The setting is the play. People enter into the room, and you listen to something that is said, that has been pre-recorded, and this is the character in a way. Enda managed to build up a cross between fine art installation and a play without characters, although the characters come through the voice that we hear. This is done with an apparent simplicity that is absolutely astonishing. The best thing I have is a quote from Virginia Woolf, from Orlando, when Orlando wakes up and finds himself as a woman and she writes, “He was a woman. And that’s all.” The transformation is said in four words, really. “She-was-a-woman”. And this is the same thing that Enda has accomplished with Rooms. It’s a project that is ongoing, isn’t it? Can you speak to us about this project which I find absolutely fascinating?

EW: To explain for everyone, what the Rooms plays look like from the outside are giant white boxes with a door in it. They’re just in the space. I do one a year. You open the door and there is a super-realistic setting. It might be a two-star hotel room, it might be a kitchen in a suburban house, a waiting room in a hospital. I’ve just done a dining room with an exploded dining room table. I started making them 11 years ago and I decided I should make one every year until I die. It goes back to when I started writing when I was 14, and I said to my mother, “Writing is just about meeting strangers.” and I thought I should go back to that initial thing. I’m obsessed with structure on stage with theatre, but I thought with Rooms I’ll just do this incredibly simple thing. You walk in as an audience, there are only four people allowed in, you shut the door, and then this audio starts. They all last about 13, 14 minutes, and then it’s over. And the character whose voice you hear is connected to the room – maybe they’ve been in it or they are about to go in it, or they’ve left it – something. And it’s that ghost-in-the-room sort of feeling, and just a disembodied voice of a character.

There’s something quite Catholic about it, you know when you go into a confession box. You have these characters that are confessing something very private to you, and only to you, and only to four people in this space. So, it feels very shared, very delicate. And vulnerable. And wild and crazy, at times. Each one has a different color. I did one two years ago, that was the last year, that was set in 1972 in a cloakroom in a nightclub outside of Belfast. People immediately know who the character is, because they connect with the words very quickly and they connect with the space. And they want to bring the space and the character together really really quickly as we do in the theatre when we sit down. We want to know all of that. But this is like still life but in miniature. But they’re amazing things to do, it goes back to that impulse when I was a boy. They feel like I’m just creating loads of little characters like this. I’ve got 11 now. Maybe I’ll get up to 35 if I’m lucky. The idea of all of them playing together [being staged simultaneously] and walking into a gymnasium and seeing all these white boxes and knowing that a person lives in there – that to me is enough. You know, it feels like a really big thing to leave behind. And it says a lot about who we are as humans.

João Carneiro: You may say the characters aren’t there, but the character is there through the voice. As you said, we understand immediately who the character is and what it is about. Although it is very brief, it goes on resonating in your mind afterwards.

EW: Well, I’m sure we’ve all had a Rooms experience. You’re sitting in a bar. I sat in a bar in Albuquerque, New Mexico talking to this guy, and it was the most extraordinary concentrated conversation, and I left there feeling like I knew his life. Of course I didn’t know his life, but I knew a lot about him. I think that’s what the pieces offer: a concentrated version of a person for a brief moment in time. And also like in all the plays I’ve written, the characters are all meeting a point of crisis. There’s a Mary in Medicine, but there is a thing, like, doing what we’re doing isn’t right. That completely detonates a whole performance. The structure is the structure; it exists. But then one of the characters says, “This is bullshit! We shouldn’t be doing this.” And then it re-forms in a different way. And then it is about the effect of the kinetic physical violence of the play on the character. And the character is trying to beat the play, and the play is trying to beat the character.

But in these smaller plays, Rooms, you’re listening to a character – like this guy in Albuquerque, he told me something personal, it was an incredible thing to share but I was there for it, and I think in these Rooms, you’re there for it, you’re listening to it, that’s why they feel confessional. The characters reach a moment of … whatever, of understanding of something. Maybe they fall back into exactly what they’re doing, or maybe they change slightly – maybe the act of saying “This is who I am” is enough for them?

I have a love-hate relationship with words – words really let you down, I know they are the only thing I have as a writer, but they don’t get to the point. They surround the point, that’s their job, but they never really get there. That’s why theatre is interesting, because it is a collaboration of movement and words and sound and everything else that sort of gets to the point. It gets to the subtext. My relationship with words all my life is that they really let me down. First, I couldn’t speak them, and when I could speak them, they were never good enough. Rooms has taught me to love them a little bit more.

Audience question to the director António Simão: You have produced many Enda Walsh plays. Why? What about his work speaks to Portuguese people?

Rémedio director António Simão: If you remember, there was the economic crisis in 2008; the countries affected were Portugal, Greece and Ireland. So, I think we have the crisis in common. In general, the structure and form that Enda found in his plays touches me. The plays have slapstick with poetry, bad language with philosophy – it’s a very rich patchwork I find very interesting to work with. He can at the same time combine pub talk, like two guys drinking a beer and saying “Fuck!” and all that with, on the other hand, a play that is intellectual and lyrical, more exclusive with ideas and words. So, his plays are a kind of fruit salad that for me is very interesting. And it has something to do with us as Portuguese, because it is about people trying to live and trying to think – it has a bit of existentialism: “Why am I doing this, what am I doing here?” And Enda writes a lot, so I like it. I like many words. The language is very powerful. It reaches our ears.

Audience question to EW: Some of your critics describe you as an absurdist playwright. Do you agree with them?

EW: Sometimes I do. I really bonded with my dad over many things, but one of the big things was that in Ireland our local network RTÉ on Saturday mornings got a load of Laurel and Hardy and all the black and white movies, and so I became obsessed with silent actors and physical comedy. The Three Stooges was a massive thing for me. And the Marx Brothers later on. They are completely absurd. Characters who are trying to solve a problem but they end up doing it in a completely slapstick way.

I did a farce, The Walworth Farce … and we don’t have farce in Irish theatre, it seems like a disgusting trite thing to do. In my eyes, farce is a very West End and Molière sort of thing. Also, farce isn’t about character, it’s about mathematics and movement and choreography, and I thought that was interesting to me, so the more I directed, the more physical the work got actually. I leaned back into an absurdist way of behaving. It’s looking at the characters not being able to communicate, not being able to find the words correctly. In Ballyturk, the characters run out of the right things to say. So, they exercise until they are absolutely exhausted on stage, and then they begin to find new words. The whole absurdist, physical, choreography thing is me adding pressure on the characters in a comedic way, but also the comedy stops, and it becomes really sad very quickly. And it has to do with them trying to articulate where they’re at. But I like a gag, and I like a joke. And I’ve worked with physical actors like Cillian Murphy. You know him from films, but he is an incredibly funny actor on stage. Buster Keaton had a huge effect on Misterman when we did it the second time. And Buster Keaton is absurdist. The relationship between character and environment in Buster Keaton films had a massive effect on me. I want to have a character try to control a stage that is completely uncontrollable like in Buster Keaton, so I started putting that into the work, and an audience can, I think, enjoy that but also feel a bit nervous. Which is good.

The transcription of Enda Walsh’s talk is by Dana Rufolo.